On the 26th anniversary of the military crackdown on protesters in Beijing and elsewhere in China, the government is carrying out the routine round-ups of activists who might try to commemorate the anniversary, as well as banning the relevant digits of 64 and 89, even from online financial transactions. Despite the censorship, the annual calls for accountability—such as those from the Tiananmen Mothers—were joined this year by a new voice: Chinese students studying overseas. An open letter penned by 11 students in the U.S., Australia, and the U.K., was addressed not to the government but to their fellow students in China as an effort to educate them about an event that otherwise goes largely unmentioned there. Human Rights Watch’s Sophie Richardson writes in Quartz:

The letter by the students, who may have not been born in 1989, shows that demands for accountability aren’t going away. It asks not only why troops opened fire, but why the government still refuses to publish the death toll. Citing harassment of the Tiananmen Mothers and others who have tried to commemorate the massacre or challenge the official version of events, the letter says, “The suppression has never stopped.”

It’s hard to know which aspect of the letter—or simply the fact of its existence—causes the most dismay in official circles. Perhaps it’s the claim that, “The gunfire on June 4 shot dead [the Communist party’s] legitimacy.”

It may be the play on current President Xi Jinping’s notion of a “China Dream”—one he uses to justify a mix of economic growth, state repression, and more than a dash of nationalism. These students have a different vision: one in which China becomes “a country free of fear where history is restored and justice realized.” [Source]

AP interviewed Gu Yi, a chemistry student at University of Georgia who is from southwest China and who initiated the letter:

“We do not ask the (Chinese Communist Party) to redress the events of that spring as killers are not the ones we turn to to clear the names of the dead, but killers must be tried,” the letter reads. “We do not forget, nor forgive, until justice is done and the ongoing persecution is halted.”

An online copy of the document has reached readers in China with the help of software that let PDFs get past Chinese censors, Gu said. The document has already drawn a strong rebuke from the Communist Party-run Global Times, which said in an editorial that the students “harshly attacked the current Chinese regime, twisting the facts of 26 years ago with narratives of some overseas hostile forces.”

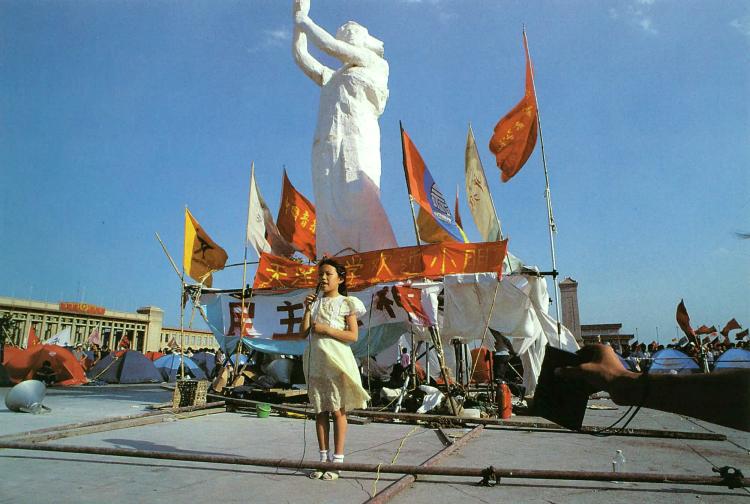

Gu said he was addressing Chinese students who had not seen the troves of photos, film footage and eyewitness accounts about the massacre that he came across only after he left China to study.

“All they need to know is actually very simple,” Gu said. “Some people died, and some people killed them. If you understand that, you don’t have to understand a lot more.” [Source]

Asia Society’s Eric Fish also spoke with Gu about political activism among his generation:

Some have suggested that most Chinese activists are from the older generation, and that this kind of action is relatively rare among post-80s and post-90s Chinese who grew up after 1989. Do you agree?

My action is to some extent conservative. We actually do have a lot of post-80s and post-90s activists in China and abroad. They’re probably not so famous. One example is a college student in Beijing who suggested last year that we could use some special method to deliver politically sensitive messages to Chinese mobile phones. Her suggestion was very creative, but it also led to her sudden disappearance, and finally, her confirmed arrest. She was a very brave girl.There was another girl named Liu Di, a freelance writer born in 1981. When she was a student, she was very active online and wrote some articles and commentaries. She was also arrested and put in jail for about a year, but when she was released she didn’t change. She kept writing and she contributed to some freethinking in China.

We actually do have a lot of activists, but we have to admit that the relative proportion of these activists in the overall population is still small. Many people don’t have the information, or they are simply not interested. Many people know what this government is and what’s going on, but they choose to have their own personal lives without getting involved in politics and those complexities. This is just their personal choice.

[…] How did you feel about China’s government before coming to the U.S.?

Actually I’ve been a dissident for a long time, but I wasn’t active before coming here. A lot of people, including me and other people in China, just dislike the Communist Party. We know the Party is far away from what it claims to be, but we don’t necessarily stand up. Many people choose to stay inside the system and get the best advantage from it and the Party. For me, the Party lost all its legitimacy after it fired on its own people. [Source]

[For more on Fish’s views of China’s millennial generation, see a CDT interview with him.]

Catherine Wang, a writer in Beijing who was born in 1989, writes for The Anthill about her efforts to come to terms with this part of her country’s history after she, like Gu Yi, learned the full story of June 4th by searching for information online:

All afternoon, I sat in front of my laptop using a VPN to read reports on foreign websites for the first time, and watch videos of what happened twenty years ago, including of the “tank man”. Even the most hard-hearted person would have been shocked at what I saw. With tears in my eyes, I couldn’t stop searching for more images from that night.

I still have the photo from 1998 when I first visited Tiananmen square. I was nine years old, smiling, with PLA soldiers standing behind me. I was so proud of the national emblems everywhere, of the slogan “Long live the PRC” above the gate of the Forbidden City, and of the soldiers with guns which are supposed to protect the nation and its people. But now it all changed. My tears were not just for those who died on June 4th, but also for myself. It hurts when the world you have built up in your mind for twenty years collapses. [Source]

Other commentators have looked at the legacy of June 4th and its connection with the current corruption epidemic. Several of the older activists who experienced or participated in the 1989 protests see June 4th as a dividing line in China’s history which set the Chinese government on the path to corruption. Bao Tong, former aide to deposed Party leader Zhao Ziyang, who remains under house arrest in Beijing, wrote an opinion piece for the New York Times linking June 4th, Deng Xiaoping’s opening and reform policy, and endemic corruption:

Deng, through his actions on June 4, drew new demarcation lines to define enemies. The party would protect corruption, and anyone who opposed party-supported corruption was a deadly foe of both the party and the army.

Following the 18th Party Congress, the movement to “slay tigers and swat flies” struck China like a series of thunderbolts. The anti-corruption crackdown seems like an epochal event, but perhaps its greatest usefulness has been in opening people’s eyes. China’s red flag, dyed in the blood of martyrs, has become a shelter for evil people and practices. The legions of corrupt officials exposed may be only the tip of the iceberg, but these revelations have already eclipsed other reported instances of corruption in China or abroad. There is no longer any way of concealing this top-to-bottom corruption, no chance of erasing knowledge of it from people’s minds.

But while the party’s fight against corruption is presented as a public service, if independent citizens — members of civil society — take up the cause, it is a crime.

Popular movements to combat corruption are, as they were in 1989, sternly repressed. China’s put-upon and bullied citizens are denied legal redress, through the court system or petitions to the central government. Indeed, people who have exposed corruption have found themselves put on trial or in prison. Universal values like transparency and accountability are smeared as tools of overseas enemies causing trouble. Meanwhile the limitless power of the party to meddle has only increased, as it co-opts concepts like the rule of law, technology and globalization. [Source]

Exiled writer Hu Ping makes a similar point in a piece published on China Change:

The Tiananmen massacre did two things: it stunted China’s political reforms, and it put the country’s economic development on a deviant path. Public sentiment was so badly crushed during June 4 that the privatization agenda which soon came to China lacked even the most basic public participation or supervision, and devolved into a naked wealth grab by those with power. Officials mighty and small got involved in unrestrained asset stripping in the name of “reform,” turning what belonged to the commonweal into their own personal property.

Oddly, this cronyist privatization, while morally base and sordid, is probably one of the most effective and rapid means of transforming a state-run economy—for the simple fact that it avoids the fragmentation of capital that would have occurred in a truly public process. This, in turn, prevented an economic slowdown, and ensured growth—for a time.

On top of this, China was able to ride on the coattails of globalization, sucking in massive amounts of international capital, technology, and managerial know-how, while exploiting its ability to give the lowest possible wages and conditions to its workers. All this took place as the Party encouraged the masses to forget about politics and simply make as much money as possible, ensuring that the worst form of capitalist excess was delivered with the most competitive punch.

China’s economic development is indeed dazzling. But it has a fatal flaw: it lacks legitimacy. The Chinese Communist Party rose to power by lynching landlords and capitalists and dividing up the spoils, and now the Party itself has become China’s biggest landlord and capitalist. In the name of revolution, it took from the individual and gave to the so-called collective, and later, in the name of reform, it stole from the collective and lined the pockets of its own members. [Source]

Activist Chen Guangcheng also believes the events of 1989 opened the door to widespread corruption and fraud. He writes in the Washington Post:

Now, a quarter-century later, fantastical tales of China’s economic might and rapid development dazzle the world. But these stories obscure a cruder reality: Connection, corruption and fraud have funneled most of the nation’s wealth into the hands of the elite. The government issues reports of increased GDP (though it has a propensity to manipulate its statistics), while the country’s natural environment has been devastated, the rule of law has deteriorated and human rights have been trampled under an iron heel. For many people, life in the countryside is more difficult than ever.

To this day, the Communist Party does not dare admit the truth of 1989. It doesn’t want the Chinese people to know what really happened in that year — because it still doesn’t want to take China down a normal track of democracy, rule of law and liberty. [Source]

See also a first-person account of Beijing in the spring and fall of 1989 from Italian journalist Ilaria Maria Sala.