Last year on the eve of International Women’s Day, March 8, five women’s rights activists were detained on suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” after planning education campaigns in Beijing, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou. After more than a month in detention amid outcry from the international community, the five—Wei Tingting, Wang Man, Zheng Churan, Li Tingting, and Wu Rongrong—were all released, though they remain “criminal suspects” and continue to face restrictions and surveillance. A year after their original detention, again on the eve of International Women’s Day and following the passing of China’s first domestic violence law (which went into effect on March 1), The New York Times’ Didi Kirsten Tatlow reports on the activists’ continued struggle for the advancement of women’s rights in China, and for the legal clearing of their own names:

A year later, the charges against them remain, leaving them in legal limbo, their lawyers said. At the end of February, the lawyers issued a joint statement addressed to the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the National People’s Congress, which is meeting in Beijing, calling the case a miscarriage of justice and asking why the prosecution had not withdrawn it.

“From then until now, not a single legal body of state has answered our questions,” Ge Wenxiu, a lawyer for Ms. Wei, said in an interview.

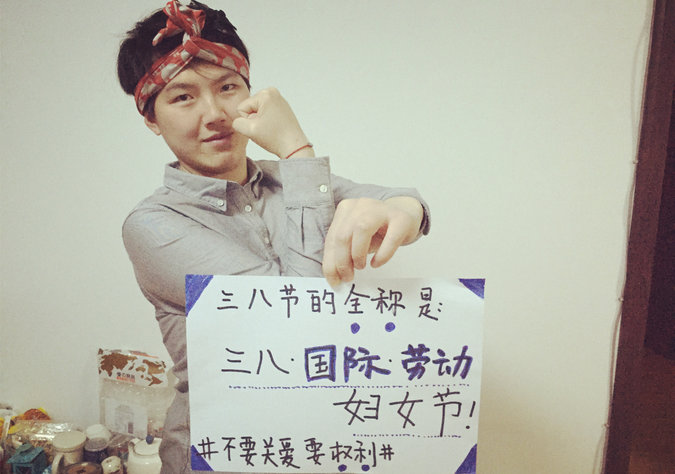

[…] Advocating feminism “in a mild way,” as others had for decades, had failed, and Chinese feminists needed “a more intense way” to achieve their goals, she wrote on Facebook in English to explain a high-profile approach that began in 2012 and has included actions such as appearing in bloodied bridal gowns, occupying men’s toilets and wearing giant paper underpants.

“Like all the social movements, the Chinese feminist movement has experienced climaxes and bottoms,” Ms. Li [Tingting, aka Li Maizi] wrote. “Although it is greatly restrained at present, we believe that the feminism activists in China will promote it with our wisdom and brave heart.”

For Ms. Li, the new law was an achievement. She welcomed it, though her comments were measured, reflecting perhaps greater impatience and ambition among younger Chinese feminists. For example, many openly lobby for gay rights in a way older generations did not. […] [Source]

China Change has translated the joint statement from the activists’ defense counsel, and has also reported that the lawyers met pressure from authorities after submitting it:

On March 3, Internal Security police, the branch of the Public Security Bureau focused on internal political threats, sought out the defense lawyers of the feminist activists. They said that they knew that five lawyers had sent a legal opinion to the authorities recommending that the case against the the Feminist Five be withdrawn. Security police asked them which lawyer was in charge of that letter, what their motive was, and to which governmental departments it had been sent.

One lawyer responded: “Firstly, you can take me as the leader. I signed the postage for it and take full responsibility. Secondly, the motive was in the hope that the Beijing police would exhibit a modicum of legal awareness, adhere to procedure, respect human rights, and protect human rights.”

[…] Officials in the judiciary also called several of the lawyers in for talks, and among the Feminist Five, some were called in by police and talked to. [Source]

The five were released pending further investigation (qǔbǎo hòushěn 取保候审, which subjects them to surveillance and other restrictions for up to a year. In a 2011 blogpost, Siweiluozi quoted legal scholar Jerome Cohen defining it as “a technique that the public security authorities sometimes use as a face-saving device to end controversial cases that are unwise or unnecessary for them to prosecute”). On March 1, Radio Free Asia’s Wen Yuqing reported on how the continuing surveillance—set to expire this week—has been affecting the activists’ lives:

The five women, whose detention prompted an international outcry, are still officially regarded as criminal suspects in spite of protesting to the United Nations over continuing police restrictions on their movements.

“It’s hard for us to go about our lives or our work,” Zheng [Churan] told RFA. “If we leave our home province, we have to notify the police ahead of time.”

[…] “I have to ask permission to make a trip, and I can’t stay away for too long,” Wu [Rongrong] said. “I had to apply for permission to visit my parental home for Chinese New Year.”

“There is huge psychological pressure with this hanging over me, and my physical health has got worse.”

Wu said the restrictions make it hard for her to seek work, or to attend conferences linked to her field. [Source]

While the detention, release, and continued surveillance of the five women’s rights activists attracted substantial attention from the international press, discussion of the topic has been regulated on Chinese social media. At The Guardian, Yuan Ren reports on how news of the event—despite a lack of direct media attention in China—inspired two high school students in Beijing to found a feminist club:

While the western media paid close attention to the event, many Chinese women had no idea it had even happened – feminism is not necessarily big news in China.

But [Lauren] Gao did pay attention to the news and, at the end of 2014, together with a fellow student, 16-year-old Cui Yuxiao, founded the feminist club at the Dalton Academy, the international branch of the prestigious Affiliated High School of Peking University, one of the top two universities in the country.

Such a club of girls Gao’s age is more or less unheard of in China. Since November, the club has aimed to hold weekly sessions every Friday lunchtime. At each session, members present a feminist topic of interest, “with the purpose of helping other students discover something new [about feminism] that they wouldn’t see without ‘feminist lenses,’” says Gao.

[…] Cui and Gao are not your average teenagers, nor do they symbolise a new wave of mainstream feminism in China. Both attend one of the most elite schools in the country and they have access to a wide range of western resources that include lessons on feminist ideology. With its host of foreign teachers, the school even offers elective classes on Simone de Beauvoir. [Source]

Updated at 19:00 PST on March 7: A new documentary film by Shako Liu called “I Am a Feminist” follows the five women activists who were detained and explores their work fighting for gender equality in China. Watch the trailer on YouTube: