While Standing Committee member Yu Zhengsheng has said that the upcoming 3rd Plenum of the 18th CCP Congress will “initiate ‘unprecedented’ policy changes to boost economic and social reform,” many observers are now questioning how likely real change is. As the Wall Street Journal reports, Western-style political gridlock may be derailing hopes for significant reforms in the near future:

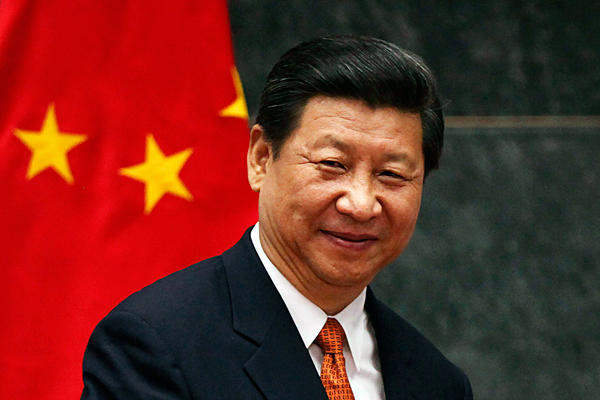

The challenge facing President Xi Jinping is how to retool the system itself before it hits real trouble. But, like his Western counterparts, that means patiently trying to build coalitions, reaching out to public constituencies, isolating his opponents, and accepting compromises.

As a result, economists have been dialing back expectations of far-reaching change from the Third Plenum.

“They’re going to be looking for a gradual transformation,” says David Dollar, formerly the U.S. Treasury’s top official in China and now a senior fellow with the Brookings Institution in Washington.

“It was never likely that we’d see radical progress,” he adds. [Source]

On the political level, Larry Diamond writes that the Communist Party is reaching the “70-year itch,” the point in their history when other single-party regimes have fallen. He questions whether President Xi will be able to initiate significant enough reforms to allow the Communist Party to survive. From the Atlantic:

[..I]t is only at the weakly organized level of society that any preparation for democratic change is taking place. Many had hoped that China’s recent leadership succession—which replaced the stolid conservative Hu Jintao with the seemingly worldly and upbeat Xi Jinping—would inaugurate a badly needed and much-delayed process of political reform. But within months of Xi’s accession to the presidency in March, those hopes had been dashed. Xi and his six colleagues on China’s super-powerful Politburo Standing Committee have wasted no time in signaling that their aim is to preserve political control and double down on ideology.

[…] To be sure, the Party is pushing hard to rein in and punish corrupt officials at various levels. It is embracing municipal efforts, like deliberative polling, to become more responsive to public concerns and preferences. And it is allowing some scope for the digital expression of public sentiment, particularly on the micro-blogging site, Sina Weibo, which hosts 100 million messages a day. All of this is meant to modernize authoritarian rule, making it more accountable and responsive without risking any erosion of the Party’s political monopoly.

[…] For Xi and his colleagues, there is a way out. They could buy significant time by launching a gradual process of democratization—something like what their old rival, the Kuomintang (KMT), did in Taiwan after losing the Chinese civil war. They could introduce competitive elections to determine who governs at lower levels of authority. Back in the late 1980s, village elections in China looked like a start down this road. By the time I observed them in 1998, a Chinese official in charge of administering them was predicting that the process of competitive elections would move briskly up the ladder of political authority. In five years, he anticipated, they would rise to the township level; in another five years to the country level; five years later to the provincial level; and then finally five years later still there would be democratic elections for the national government. 15 years after that hopeful prediction, township elections remain in an “experimental” state, village elections confer no significant governing authority, and the CCP appears frozen with fear at the prospect of opening the system to real electoral choice and accountability (even on a non-party basis). [Source]

Predicting China’s future is a notoriously risky, but lucrative, profession. But, as James Fallows warns (also in the Atlantic), “People who say they know what will happen in China, don’t”:

Do the past 30 years of growth mean (as many credulous Westerners, and a few assertive Chinese, have assumed) that China is soon destined to dominate everything, everywhere? Or is the real worry whether growth and progress can be sustained at all? Is the Chinese system too strong? Or too weak? Or both?

Will the newest crop of leaders realize, as Deng Xiaoping did 30-plus years ago, that if China is to stay Communist-run, then Chinese Communists will have to relax controls as fast as they can? Or will they keep pumping out slogans about “reform” without doing anything serious to clean up the structural imbalances, the crony-capitalist/communist corruption, and the needless intrusions (like Internet censorship) that threaten the country’s ability to move up to fully modern “rich country” status?

[…] The more confident people sound in answering the big Whither China? question, the more skeptical I’ve become of them and their views. [Source]