As China gears up for Mao Zedong’s lavish 120th birthday anniversary celebrations, Denise Ho and Christopher Young explain his rebranding from “revolutionary” to “incorruptible government official” at a memorial museum in Hunan. From The Atlantic:

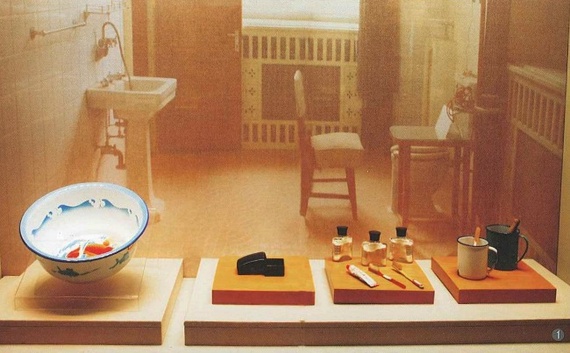

The display of personal effects is not new to Chinese museums. But in Shaoshan, the relics narrate a story not of Mao the revolutionary, but Mao the exemplary official. Tooth powder, for example, demonstrates that Mao was both frugal and conscious that most Chinese people could not afford toothpaste (never mind that toothpaste appeared later in other glass cases). His receipts were presented to show that Mao was abstemious and did not allow waste. Mao’s account books showed his finances were in order, and his letters suggested that he never obtained special favors or jobs for his relatives.

The reinvention of Mao as the good official comes at a time when the public views corruption as one of China’s biggest problems, and it is impossible to open a newspaper without seeing an article on the latest official ensnared in a probe. Indeed, Chinese president Xi Jinping has, in the year since he assumed power, launched a campaign to rid government of “flies and tigers,” referring to low-level officials and those in the highest positions of power, respectively. But while the Comrade Mao Museum tells us that Mao was a good official, it does not explain how to be one today. You can sing red songs, the museum seems to suggest, but for the truly great men of a previous age alone.

Despite the museum’s emphasis on Mao’s frugality and honesty, its entrance hall presents an entirely different image. The hall consists of a room decorated as an imperial palace, including vermillion doors with golden ringed handles, red columns, and colorful brackets. Roped off in the center of the room is an enormous replica of one of Mao’s seals, projecting an imperial stamp of authority. [Source]

While the Hunan museum emphasizes Mao’s early frugality, others are being built to showcase wealth. The Economist reports on a boom that has seen the number of museums in China go from 25 in 1949 to 3,500 in 2012:

Until recently culture was seen as strictly the party’s preserve, but now the boom in public-museum building is being echoed in the private sector. Rich collectors want to put their treasures on display in expensive new showcases. Many new museums are also being built as part of new property projects to help get them planning permission. Some may never have been intended for their stated purpose.

“We Chinese are very good at building hardware,” commented your correspondent’s interpreter after leaving yet another half-empty museum, this time in Shanghai. “Building software is another matter altogether.” In China’s museum world, “software” covers everything from building up collections to actually running the place. […] [Source]