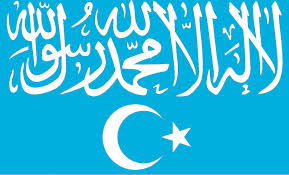

After the deadly Kunming train station attack on March 1 highlighted growing tensions between the predominately Muslim Uyghur ethnic group and China’s majority Han ethnicity, a leader of the militant separatist Turkistan Islamic Party has promised more attacks on China. From Reuters:

In a rare but brief interview, Abdullah Mansour, leader of the rebel Turkestan Islamic Party, said it was his holy duty to fight the Chinese.

“The fight against China is our Islamic responsibility and we have to fulfill it,” he said from an undisclosed location.

“China is not only our enemy, but it is the enemy of all Muslims … We have plans for many attacks in China,” he said, speaking in the Uighur language through an interpreter.

“We have a message to China that East Turkestan people and other Muslims have woken up. They cannot suppress us and Islam any more. Muslims will take revenge.” [Source]

According to Reuters’ Pakistani security sources, hundreds of Uyghurs moved to the unruly North Waziristan region on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border after China cracked down in Xinjiang following the July 2009 riots in Urumqi. China—Pakistan’s closest military, economic, and strategic ally—has been putting increased pressure on the Islamic Republic to root out Uyghur separatists, and their numbers in the region are now believed to be much smaller. The Reuters’ report linked above continues to quote the head of the Pakistani FATA Research Center, who says that China is exaggerating the power of the group: “It’s survival basically, they can’t go back. This is the only place where they’re welcome.”

The Turkistan Islamic Party, still commonly referred to as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, took credit for numerous attacks in China in 2008, though intelligence organizations have said that their “claims of responsibility appear exaggerated.” After the October 2013 Tiananmen jeep crash, Abdullah Mansour made a public statement, labeling the crash a “jihadi operation.” While Beijing blamed the March 1 attack at the Kunming Train Station on “Xinjiang separatist forces,” Mansour did not claim responsibility for the violence in his brief interview with Reuters.

For The Guardian, William Dalrymple looks at how Chinese campaigns in Central Asia, originally launched with economic goals, are becoming more security oriented, and leading to greater Sino-US cooperation in the region. Dalrymple quotes U.S. officials who also believe that Beijing’s claims of a hostile Uyghur presence in the region are exaggerated:

[…] American intelligence does not believe that the Uighur militant presence in Afghanistan or Pakistan is very large: “There must be some Uighurs there,” I was told by a US delegation member last week. “But the Chinese overdo it. The Uighurs are certainly not as significant a presence as the Uzbeks, who are definitely there and are genuinely a threat.” The primitive nature of the Kunming attack – using knives not guns or bombs – would seem to confirm that the Uighurs may be angry but they remain largely untrained and unarmed.

Nevertheless, the perceived Pakistan link to Uighur militancy has become the crucial factor in changing the Chinese approach to Afghanistan. Five years ago the Chinese viewed the country primarily as a source of hydrocarbon and mineral deposits – trillions of dollars of the oil, gas, copper, iron, gold and lithium that China will need if its economy is to expand. In 2008 Chinese Metallurgical Group and Jiangxi Copper Co bought a 30-year lease on the site of Mes Aynak in Logar for $3bn, which they estimated to be the largest copper deposit in the world. But after Taliban attacks the mine remains dormant, and Beijing now views Afghanistan more as a security problem than an economic opportunity: “Driving Chinese policy in Afghanistan now are concerns on terrorism,” said the state department official. [Source]

A number of recent events have placed Xinjiang and its native Uyghurs squarely in the global news focus: the Kunming attack, speculation that the missing Malaysian Airlines flight may have links to Uyghur terrorists (despite Beijing’s own dismissal of such theories), and detained Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti’s recent separatism charge. Wang Lixiong gives an overview of the situation in Xinjiang, explaining how Beijing’s policies are contributing to radicalization in the region. Published in translation by the New York Times:

[…] The radicalization of the Uighurs’ cause is an inevitable result of Beijing’s continued repression.

[…W]hile the economic indicators have soared, the majority Uighurs have been left behind. The best jobs have gone mostly to the Han Chinese. Uighurs lucky enough to find jobs often end up doing manual labor — toiling in coal mines, cement plants and at construction sites. Unemployment among young Uighurs is widespread. On my nine visits to Xinjiang, I have often seen bands of working-age Uighur youths loitering on the streets, whether I was in a city or in the countryside.

[…] Still, the core conflict between Beijing and the Uighurs is political, not economic. […]

[…]For years, Beijing has characterized Uighur protests as the work of a few pesky separatists, as if the Uighurs’ desire for self-rule was not a serious concern. But more than ever, Uighurs see separation from China as the solution. And many are looking beyond Chinese borders, toward militant Muslims overseas, for inspiration.

Backed into a corner by Beijing’s relentlessly antagonizing tactics, the Uighurs are likely to resort to more deadly terrorism. Xinjiang is poised to become China’s Chechnya. [Source]