Despite optimism from the Dalai Lama about progress towards his goal of Tibetan autonomy within Xi Jinping’s China, negotiations with Beijing remain at an impasse, the spiritual leader continues to age, and the future of a 400-year-old political and religious tradition is still uncertain. In 2011, the 14th Dalai Lama ceded political responsibility to democratically elected Sikyong Lobsang Sangay, ending a tradition of direct political authority that has reincarnated with the highest Gelug lama since the 17th century—if only nominally and over a stateless community of exiles since he fled Tibet in 1959. Last year, in an apparent attempt to disarm Beijing from the expected naming of his successor, the Dalai Lama repeatedly announced his intentions to be the last, sparking castigation from both CCP officials and Chinese state media. On Monday, an essay published in the Global Times by a top Party official reasserted China’s insistence on appointing the next Dalai Lama. Reuters’ Sui-Lee Wee reports:

The central government has stiffened its resolve to decide on the reincarnation of “living Buddhas, so as to ensure victory over the anti-separatist struggle”, Zhu Weiqun, chairman of the ethnic and religious affairs committee of the top advisory body to China’s parliament, wrote in the state-run Global Times.

[…] In a commentary, Zhu said the issue “has never been purely a religious matter or to do with the Dalai Lama’s individual rights; it is first and foremost an important political matter in Tibet and an important manifestation of the Chinese central government’s sovereignty over Tibet”.

As the Dalai Lama is the first political leader of Tibet, “whoever has the name of Dalai Lama will control political power in Tibet,” Zhu added.

“For this reason, since historical times, the central government has never given up, and will never give up, the right to decide the reincarnation affairs of the Dalai Lama,” Zhu wrote.

“It is not only necessary, but is in line with jurisprudence, and has nothing to do with whether the rulers believe in religion or not.”

The Dalai Lama has said his biggest concern was that China would name his successor, saying, “The precedent has been set”. [Source]

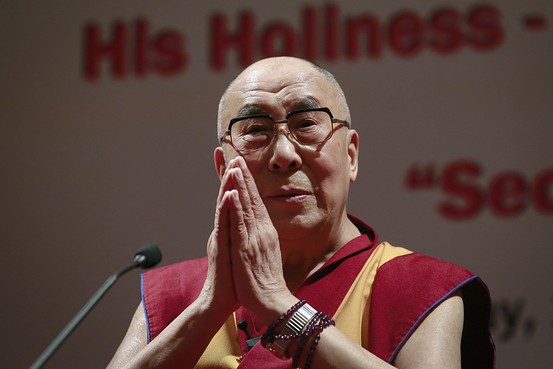

At the New York Times, writer Pankaj Mishra profiles the aging Tibetan spiritual leader, a man whose “life can seem one long, heroic effort to resolve the contradictions of being both a committed monk and a reluctant politician.” The essay paints a picture of the fragile politics—of globalization, diplomacy, cultural maintenance, traditional and new-age religiosity, softened calls for statehood, and a factionalizing exile community—that have defined the 80-year-old monk’s life, and asks what the absence of his role might mean for Tibetans in exile:

[…] I first saw the Dalai Lama in the dusty North Indian town Bodh Gaya in 1985, four years before he won the Nobel Peace Prize. Speaking without notes for an entire day, he explicated, with remarkable vigor, arcane Buddhist texts to a small crowd at the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment. Thirty years later, at our first meeting, in May of last year, he was still highly alert; a careful listener, he leaned forward in his chair as he spoke. When I asked him about the spate of self-immolations by Buddhist monks in Tibet, he looked pained.

[…] He then quickly reminded me that he had renounced his political responsibilities, ending a four-century-old tradition according to which the Dalai Lama exercised political as well as spiritual authority over Tibetans. As part of his democratic reforms, an elected leader of the Tibetan government in exile now looks after temporal matters; he also deals with diplomatic and geopolitical issues. ‘‘My concern now,’’ the Dalai Lama said, ‘‘is preservation of Tibetan culture.’’

[…] The prospect of a world without the Dalai Lama has created a new set of quandaries for the Tibetan community in exile, even as it still looks to him for guidance. […]

[…] The flow of refugees from Tibet, once running into the thousands, has slowed to a trickle. Many exiles have returned to Tibet, where urban and rural incomes have risen. And life for ordinary Tibetans in Dharamsala remains a struggle. They still cannot own property, and an increasing number hope to emigrate to the West. (Many of the young T.Y.C. activists I interviewed in 2005 have scattered across the world.) The United States is a favored destination; some Tibetans are doing very well there, but many have ended up working as dishwashers and janitors. Others became vulnerable to visa racketeers.

[…I]n late May this year, Lobsang Sangay said he hoped China would learn from its struggles with growing anti-mainland-Chinese sentiment in Taiwan and Hong Kong and reconsider its policy in Tibet. This seems a common expectation among the Tibetan establishment, though it is not much shared outside it. The Dalai Lama told me that the Chinese ‘‘are facing a kind of dilemma.’’ In Tibet, ‘‘they tried their best to obliterate, like Tiananmen event, but they failed.’’

In the meantime, it was imperative, Lobsang Sangay told me, for Tibetans to remain united. Tibetans, he said, needed to keep in mind four key points: survive, sustain, strengthen and succeed. Briskly, Lobsang Sangay sketched a vision in which Tibetans grow richer and more resourceful through private entrepreneurship. He said, ‘‘Mahatma Gandhi, after all, received blank checks for his activism from big Indian businessmen.’’ […] [Source]