While China’s leaders have long seen the news media as the “throat and tongue” of the Party, Xi Jinping has overseen a steady increase in the state’s control of the media narrative. While on a tour of leading state media outlets in February, Xi Jinping stressed that the media “bears the Party surname,” and must “speak for the Party and its propositions and protect the Party’s authority and unity.”

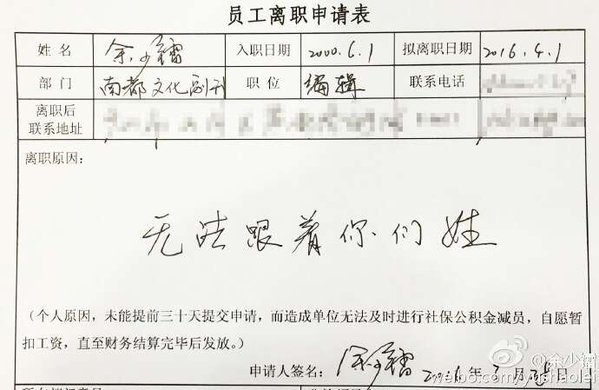

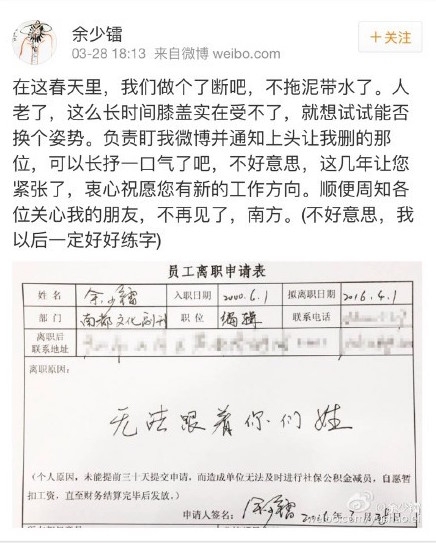

On the evening of March 28, Southern Metropolis Daily editor Yu Shaolei shared a photo of his request for resignation from the Guangzhou-based paper on Weibo. Born in 1968, Yu has worked at the paper for 16 years, and is currently a senior reporter and the editor-in-chief of the culture department. From Yu’s post:

“This spring, let’s make a clean break. I’m getting old; after bowing for so long, I can’t stand it anymore. I want to see if I can adopt a new posture. To the person responsible for monitoring my Weibo and notifying his superiors about what I should be made to delete: you can heave a sigh of relief. Sorry for the stress I’ve caused you these last few years, and I sincerely hope your career can take a new direction. And to those friends who care about me, I won’t even say goodbye, Southern Media Group.” [Chinese]

On the application for resignation section asking for his reason for leaving, Yu wrote, “Inability to bear your surname” (无法跟着你们姓).

Since Xi’s state media tour, there have been several notable instances of protest from media professionals and commentators fed up with the increasingly tight media landscape in China. Retired property mogul and famously outspoken social media user Ren Zhiqiang took to Weibo to say that state media service is more indebted to the Chinese taxpayers than the Party; he was soon thereafter banished from social media. In what was either an unfortunate mistake or a clever act of dissent, the February 20 front page of Southern Metropolis Daily’s Shenzhen edition appeared to read “Media are surnamed Party, their souls return to the sea“; editor Lu Yuxia was fired for showing “a serious lack of political sensitivity.”

Earlier this month, Xinhua employee Zhou Fang posted an open letter denouncing censorship for “triggering tremendous fear and outrage among the public, [who] worry about another Cultural Revolution.” Another open letter, posted on a state-linked news website Wujie News and signed by “loyal Party members,” called for Xi Jinping’s resignation for his role in fostering a culture of fear on the political diplomatic, economic, and ideological fronts. On the ideological front, the letter read, “Your emphasis of the ‘media’s Party surname,’ has disregarded the media’s character of representing the people, and the entire country is stunned.” The call for Xi’s resignation has sparked a new crackdown, in which a journalist, staff from Wujie News, and the family members of several overseas-based critics have been detained or harassed by authorities.

Former Southern Metropolis Daily editor Li Xin, who fled China in 2015 claiming that he had been forced by authorities to spy on colleagues, last month reappeared in China under detention. Li was reportedly detained in Thailand where he was planning to seek U.S. asylum, becoming the latest of several to disappear from a foreign country into Chinese detention.