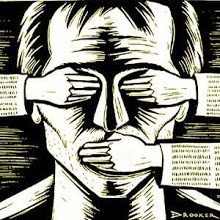

The Cyberspace Administration of China has launched a new drive to “vigorously purify the online commentary space,” focused on the comment sections of news sites. In a televised conference, CAC Deputy Director Ren Xianliang called on websites to weed out “harmful information” (有害信息) from among comments—or “illegal or malignant content,” as phrased by Xinhua. From the CAC website:

There are three facets to this earmarked work: The first is to gather and cleanse harmful commentary that violates the “nine forbiddens” and “seven base lines,” and to vigorously purify the online commentary space. The second is to strengthen enforcement, supervision, and management; to keep clear the channels for online reporting [of violations]; and to promote a good system of mass prevention and treatment in which everyone shouts out and beats down harmful information. The third is to extensively develop online propaganda and education; actively cultivate a positive, healthy, progressive, and charitable internet culture; and to make civilized commentary, rational posts, and well-intended responses the norm.

Ren Xianliang emphasized that the key to putting commentary in order lies in websites fulfilling primary responsibility. Online media can’t always jockey for more clicks, but must conscientiously shoulder the burden of reaching the utmost in social responsibility. They must perfect the information safety management system, strengthen self-management of commentary, make good on their solemn promise to the public, and facilitate the internet bringing benefit to the people. [Chinese]

Leaders from state media and internet news sites were in attendance, including Global Times head Xu Dandan, Tencent deputy editor-in-chief Chen Peng, and NetEase deputy editor-in-chief Liu Yang. Chinese internet companies have long assumed the burden of censorship, as CDT’s ongoing project documenting keyword filtering on Weibo shows. But a report from Initium notes that the shift of focus from individual internet users to media sites distinguishes this new campaign, particularly in the wake of outspoken tycoon Ren Zhiqiang’s purging from social media earlier this year.

The “seven base lines” (七条底线) for online speech were released at the China Internet Conference in August 2013. They ask netizens to uphold “the Socialist System” and national interests, as well as legality, morality, and truthfulness. The “nine forbiddens” (九不准) emerged from Article 6 of the “Internet User Account Name Management Provisions,” released by the CAC in February 2015:

Any organization or individual who registers for and uses an online account name must not be engaged in the following:

- Violating the constitution, laws, or regulations;

- Endangering national security, leaking state secrets, subverting the national regime, or harming national unity;

- Damaging the honor and interests of the country, or damaging the public interest;

- Inciting ethnic hatred or discrimination, or harming ethnic unity;

- Harming national religious policy, or promoting evil cults and feudal superstitions;

- Spreading rumors, disturbing social order, or harming social stability;

- Spreading [content that is] obscene, pornographic, [about] gambling, violent, [about] murder, [about] terrorism, or instigating crime;

- Humiliating, slandering, or encroaching on the lawful rights and interests of others;

- [Posting] other content prohibited by law or administrative regulation. [Chinese]

The CAC’s latest campaign is part of an ongoing trend towards the limitation of online speech not just in China, but globally. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development released a report today warning that “regulatory barriers to digital innovation,” among them barriers to free expression, hamper the growth of the worldwide digital economy. Reuters’ Tasmeen Abutaleb and Alastair Sharp summarize the trends found by the OECD:

China and Iran long have restricted online speech. Now limitations are under discussion in countries that have had a more open approach to speech, including Brazil, Malaysia, Pakistan, Bolivia, Kenya and Nigeria.

Advocates said some of the proposals would criminalize conversations online that otherwise would be protected under the countries’ constitutions. Some use broad language to outlaw online postings that “disturb the public order” or “convey false statements” – formulations that could enable crackdowns on political speech, critics said.

[…] Turkey and Thailand also have cracked down on online speech, and a number of developing world countries have unplugged social media sites altogether during elections and other sensitive moments. In the U.S. as well, some have called for restrictions on Internet communications. [Source]