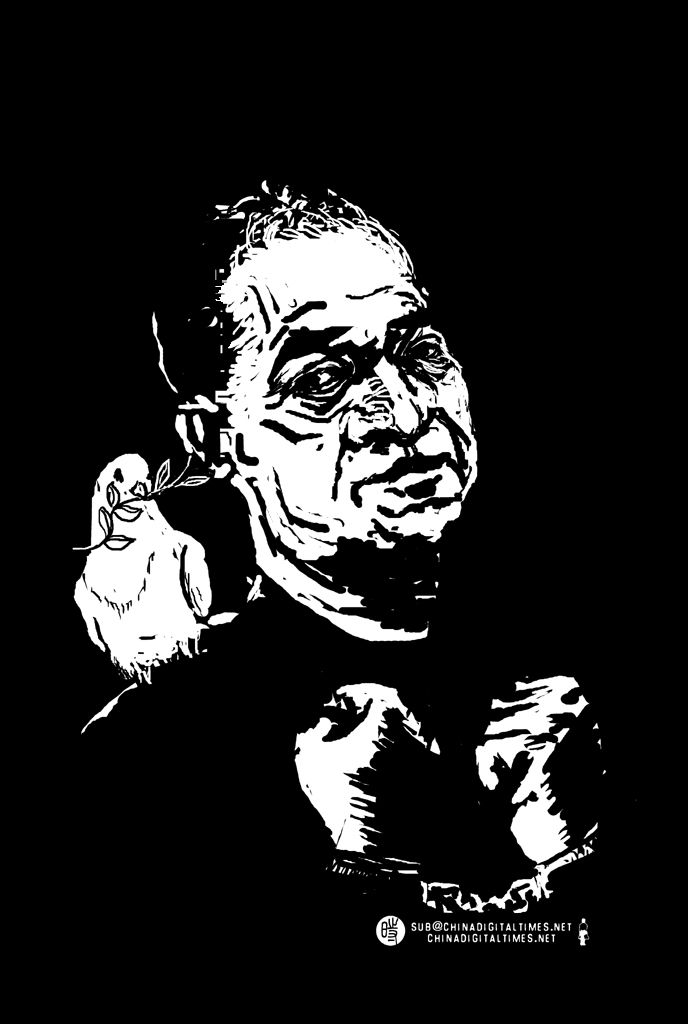

After being detained in early 2014 and formally charged that July, Uyghur intellectual Ilham Tohti was sentenced to life in prison for separatism in September 2014. The scholar and activist was known widely as a moderate working to foster dialogue between Uyghurs and Han in the troubled Xinjiang region—commentators noted that his moderation may have been what made him a target: “They don’t want moderate Uyghurs,” scholar Wang Lixiong said shortly after his trial, “Because if you have moderate Uyghurs, why aren’t you talking to them?” Some warned that Ilham Tohti’s harsh sentence could fuel radicalism in Xinjiang, where a heavy-handed crackdown on terrorism targeting mostly ethnic Uyghurs is seen by critics as a major force exacerbating tensions in the region.

After it was announced in April that the jailed Uyghur scholar’s had been nominated for the Martin Ennals Foundation’s annual human rights award, Ilham Tohti on Tuesday was awarded the prominent prize. Ilham Tohti was also nominated last month for the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought. At The New York Times, Nick Cumming-Bruce reports:

Mr. Tohti, an economics professor at Minzu University in Beijing at the time of his arrest in January 2014, was named the winner of the Martin Ennals Foundation’s annual award, sometimes called the Nobel of human rights prizes, for two decades of work trying to defuse tensions between Uighurs and ethnic Han and promoting respect for Uighur culture. The Han are the dominant ethnic group in China.

“He has rejected separatism and violence, and sought reconciliation based on a respect for Uighur culture,” the foundation said in its announcement of the award, which flatly contradicts the Chinese government’s depiction of Mr. Tohti as a dangerous separatist propagating hatred and extremism.

[…] The award, decided by a panel of 10 of the world’s leading human rights organizations, is certain to anger China. Officials there lobbied the Swiss federal authorities and the foundation in 2014 after it nominated another Chinese dissident, Cao Shunli, who died that year in prison. China’s Foreign Ministry reacted angrily in April 2014 when Mr. Tohti received an American human rights award for writers.

“When you attack the moderates, as the Chinese state is doing, and attack someone so harshly that someone like Ilham receives a life sentence for doing nothing that any liberal regime would consider a crime — in other words, he was simply expressing his opinion — what you do is that you leave the field open only to the extremists,” Elliot Sperling, an associate professor of Tibetan studies in the Central Eurasian studies department at Indiana University, said in the film profile of Mr. Tohti. [Source]

Yes. They will claim it's politicized. But giving a respected scholar a life sentence is itself a political act

— William Nee (@williamnee) October 11, 2016

At The Washington Post, Simon Denyer and Emily Rauhala report further on anger over the award from Chinese authorities who insist that Ilham Tohti got was he deserved, contrasting Beijing’s narrative with praise from international rights advocates:

“In the classroom, Ilham Tohti openly made heroes of terrorist extremists that conducted violent terror attacks,” said [foreign] ministry spokesman Geng Shuang. “He also used his position as a lecturer to entice and coerce some people to form a group to promote and participate in East Turkestan separatist forces’ activities.”

[…] “The real shame of this situation is that by eliminating the moderate voice of Ilham Tohti, the Chinese government is in fact laying the groundwork for the very extremism it says it wants to prevent,” said the Martin Ennals Foundation’s chairman, Dick Oosting.

Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch, said that instead of criticizing the award, the Chinese government “would do better to look in the mirror — and release Tohti immediately.”When Tohti was nominated for the award, his daughter Jewher Ilham said her father had used only one weapon in the struggle for the basic rights of Uighurs: “Words. Spoken, written, distributed and posted. [Source]

Jewher Ilham accepted the award on behalf of her jailed father. The AP’s Christopher Bodeen and Jamey Keaten quote Jewher Ilham on her father’s current situation behind bars, asking if she thinks the award could serve to worsen it:

“My family visited on July 7: They told me that he’s gotten skinnier — he lost 40 pounds — and all his hair turned gray,” she told reporters ahead of the awards ceremony. “He wasn’t allowed to say anything,” other than to discuss general topics like “children, studies, and life,” she said.

She said she didn’t expect the award would worsen an already bad situation because of the life sentence, or anticipate that the government would retaliate against the family. But she said she hoped the award would increase awareness about her father.

Chinese authorities could realize the international attention to Tohti’s situation, and “they are scared that their reputation will get ruined,” said Ilham, who is a student at Indiana University in the United States. “Either it will have better effects or maybe no change — they just ignore it — but I don’t think things can get worse.” [Source]

Last month, on the two-year anniversary of Ilham Tohti’s life sentence, Human Rights Watch’s Sophie Richardson drew attention to Xi’s human rights crackdown and anti-terror campaign in Xinjiang, both of which are widely seen as an attempt by authorities to maintain stability, arguing that releasing the moderate activist would better lead to that goal:

Since then, human rights defenders and the rule of law in China have been under sustained attack from President Xi Jinping’s government. But the dynamics in Xinjiang – a region synonymous with gross discrimination against the predominantly Muslim Uyghur population, restrictions on religion and speech, economic development plans that favor Han Chinese over Uyghurs, and now a highly politicized counterterrorism campaign to stem violence – provide fertile ground for further serious human rights violations.

[…] Tohti had been well-placed to help lessen some of these tensions. He critiqued and proposed solutions to the economic discrimination against Uyghurs. He spoke passionately about how an independent legal system could ease abuses in the region. And perhaps most important, he helped Xinjiang-watchers inside and outside China understand developments there, and urged peaceful debate – not violence – among students, scholars, and others.

In heartening gestures of solidarity and recognition, the Martin Ennals Foundation and the European Parliament have recently announced that Professor Tohti is a finalist for their prominent human rights awards this year. But if Beijing was actually serious about stability, economic development, and respect for human rights in Xinjiang, it would give itself and many others the most important prize: Ilham Tohti’s freedom. [Source]

If #China govt had slightest interest in real equality, stability, it would release #IlhamTohti. Now.

— Sophie Richardson (@SophieDRich) October 11, 2016

#China is feeding extremism by killing off opportunities for debate, criticism. –Elliot Sperling @martinennals #IlhamTohti

— Sophie Richardson (@SophieDRich) October 11, 2016

Read more about Ilham Tohti via CDT. Also follow the ongoing crackdowns on human rights and terrorism in Xinjiang.