A new report from the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab analyzes keyword and image censorship on Weibo and WeChat related to Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Chinese political Liu Xiaobo, who died on July 13 from multiple organ failure while under treatment for late-stage terminal liver cancer. Citizen Lab’s analysis shows that the number of blacklisted images and keywords expanded significantly after his death, illustrates that sensitivity increased depending on how many potential views a post could have, and suggests that there is a continuing interest among Chinese netizens in making and viewing content related to Liu. From the full report:

Following his death, news articles reported cases of social media in China blocking references to Liu Xiaobo and his legacy. In this report we analyze censorship related to Liu and his death on two of China’s most popular platforms: WeChat and Sina Weibo.

On WeChat, we collected keywords that trigger message censorship related to Liu Xiaobo before and after his death. Before his death, messages were blocked that contained his name in combination with other words, for example those related to his medical treatment or requests to receive care abroad. However, after his death, we found that simply including his name was enough to trigger blocking of messages, in English and both simplified and traditional Chinese. In other words, WeChat issued a blanket ban on his name after his death, greatly expanding the scope of censorship.

[…] Weibo allows users to search the entire platform for relevant posts. Past research has found that search results are heavily filtered. We confirm through testing done after Liu’s death that there is a blanket block on any search terms containing Liu Xiaobo’s name in English, simplified Chinese, and traditional Chinese. This search blocking does not seem to be a reaction to Liu Xiaobo’s recent illness or death as his name has been fairly consistently blocked on Weibo search in recent years.

However, since his passing, even searches that only contain his given name (Xiaobo, 晓波, or 曉波) are blocked. According to testing by GreatFire, his given name was accessible as recently as June 14. Like WeChat, Weibo has intensified censorship, recognizing that Liu’s passing is a particularly sensitive event.

[…] Although censorship on Weibo has made finding information about Liu using his proper name impossible, we can still assess that there is interest in Liu-related content in a number of ways. […] [Source]

Read CDT coverage of Citizen Lab’s past reports on Chinese censorship and hacking, including of their discovery this year of WeChat’s unprecedented censorship of images related to the 2015 “Black Friday” or “709” crackdown on rights advocates. Another recent report from Citizen Lab examined a series of unsuccessful phishing attempts against CDT in February.

Following the announcement of Liu’s illness, authorities censored related news and commentary, and following his death CDT found several terms blocked from being posted or searched on Weibo (however, many netizens still managed to offer veiled support for and commemoration of the late Nobel laureate). In her coverage of the new Citizen Lab report, The New York Times’ Amy Qin notes ways that Liu’s supporters managed to make it past the increased censorship, and describes online commentary on official media coverage of Liu’s cremation and sea burial last weekend:

[…E]ven as censors stepped up scrutiny in recent days, many savvy Chinese internet users found ways to evade those efforts. In tributes to Mr. Liu, users referred to him as “Brother Liu” or even “XXX.” They posted passages from his poems and abstract illustrations of Mr. Liu and his wife, Liu Xia.

Over the weekend, however, the tributes gave way to scathing critiques as friends and supporters of Mr. Liu reacted angrily to the news of Mr. Liu’s cremation and sea burial under strict government oversight.

One user took to his WeChat feed on Sunday to express disgust with the use of Mr. Liu’s corpse in what some called a blatant propaganda exercise. “Swift cremation, swift sea burial,” he wrote. “Scared of the living, scared of the dead, and even more scared of the dead who are immortal.” [Source]

On his personal blog, Citizen Lab director Ron Deibert summarizes the findings of the report in the context of Liu Xiaobo’s extreme sensitivity in authoritarian China:

The passing of Liu Xiaobo is a very sensitive event for the Chinese Communist Party. The 1989 Tiananmen Square protests grew out of the mourning of the death of another person advocating for greater government transparency and reform, Hu Yaobang.

Concerned that martyrdom around Liu may spur similar collective action, as well as being concerned about saving face, the kneejerk reaction of China’s authorities is to quash all public discussion of Liu, which in today’s world translates into censorship on social media.

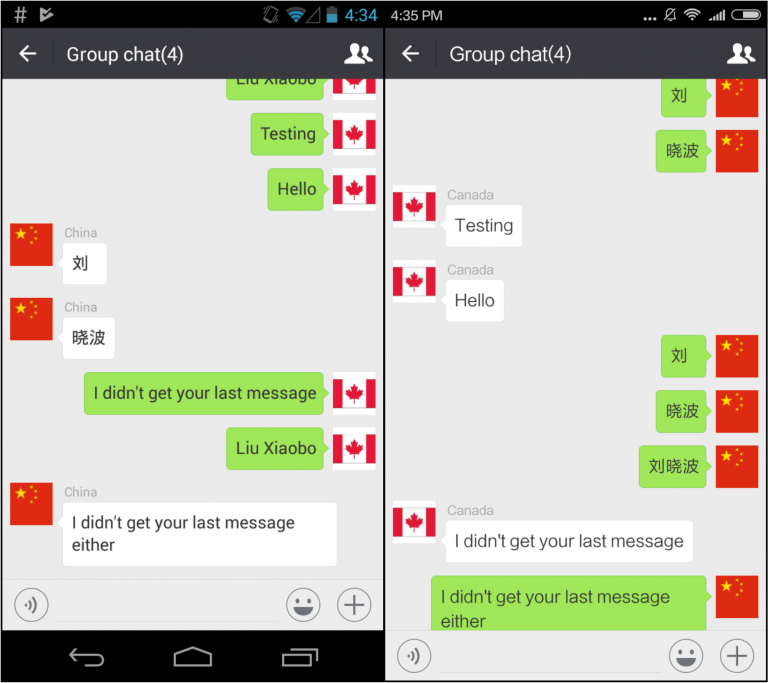

[…] As with our prior WeChat research, we confirmed that the censorship is undertaken without any notification to the users, and only applies to users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers. For example, we show that images of Liu posted to an international user’s WeChat feed was visible to other users abroad, but hidden from users with Chinese accounts.

[…] Freedom of speech is the antithesis to one-party rule. Dictators throughout history have forced embarrassing truths into the shadows, typically by imprisoning those who speak it, and have scrubbed dissidents from history books, photographs, and other mass media.

The social media censorship we document in our latest report is but the latest manifestation of this authoritarian tendency, and underscores why careful evidence-based research is so essential to the progress of human rights. [Source]

In a post on her personal blog, Citizen Lab research fellow Lotus Ruan, who contributed to the new Citizen Lab report, commemorates Liu’s life and death, imploring those in mainland China to help ensure a lasting memory of Liu, and asking what implications authorities’ treatment of Liu in his final days could have on Beijing’s efforts to become a global leader:

There are enough media coverage on Liu’s passing. What we should reflect next is the significance and indications of Liu’s death: what it means for us as an individual, to China as a country that longs to become a global leader, and to the international community in general.

To each of us, the challenge lies in how not to let Liu Xiaobo and his legacy become one of the “Top 10 Trending Topics on Weibo” that would fade away as time goes by and more importantly, how not to let Liu Xiaobo become a collective amnesia. I am not saying that people, especially those based in mainland China, should take extreme forms of protests regardless of any consequences. Even simple acts such as telling friends who do not know or even hear of Liu Xiaobo, remembering and writing about him even in coded messages will be enough to keep the conversation and people’s interest going.

To Chinese leaders, how they deal with Liu Xia, Liu Xiaobo’s wife who has effectively been under house arrest since Liu’s imprisonment, will make a difference in how the world sees their governance and legitimacy. This is also a moment for China to reflect on its development path as it longs to become a global leader. Does it want to be known as a country with only economic achievement and no amicable soft power or one that as it becomes more affluent also matures into a more humane and tolerant state? The first option has gotten China a ticket to many world clubs and international organizations. But will it help China be accepted and become a true rule maker? [Source]

Read more coverage of the Citizen Lab report, including a round-up of the carefully staged official media coverage of Liu’s passing, from Global Voices Oiwan Lam.

China’s social media censors found an additional focus over the weekend. At What’s on Weibo, Manya Koetse describes their resurgent attention to posts showing cartoon bear Winnie the Pooh, who since 2013 has been used as a meme to mock President Xi Jinping. An ongoing “clampdown” on the animated bear may be related to heightened sensitivities in the lead-up to the 19th Party Congress this autumn.