A crackdown on unsafe dwellings following a fire that killed 19 in a textile manufacturing district of Beijing has led to the sudden eviction of tens of thousands of migrant workers and the demolition of housing for many in the city. Photos of the Xihongmen section of Beijing showed decimated neighborhoods:

Insane. Rubble as far as the eye can see at site of #Beijing garment district fire pic.twitter.com/Oy3bDeo1eY

— Rebecca Davis (@rebeccaludavis) November 27, 2017

To clarify: the rubble isn't due to the fire, but to the demolition of 西红门 village south of #Beijing as authorities clear out migrants from buildings not up to code

— Rebecca Davis (@rebeccaludavis) November 27, 2017

The phrase “low-end population” (低端人口) has been used in official documents to describe the population that is being evicted, which has helped generate public sympathy for their plight. Yet some residents who tried to come to the aid of the evicted migrant workers were asked to stop their work, according to a report by Simon Denyer and Luna Lin of The Washington Post:

Hundreds of volunteers have gathered to help migrant workers with offers of temporary accommodation or assistance in moving their belongings. Others have brought soup or food to the evicted people, or donated warm clothes. Many more have taken to the Internet to declare their anger, sharing videos and photos of migrants thrown out of their homes. And more than 100 scholars, lawyers and artists signed an open letter protesting the evictions

But as the year draws to a close, tens of thousands of migrant workers are being tossed out of their homes in the freezing cold and biting winds of the Beijing winter, with little or no notice. It is a mass eviction sparked by a fire in a crammed and unsafe apartment building on Nov. 18 that killed 19 people, but it is part of a broader plan to modernize, beautify and gentrify the Chinese capital as a showcase for the Communist Party.

To many Beijing residents, it’s seen as callous and cruel. It also has touched off a rare outpouring of sympathy from the middle class toward the poorer sections of society who form the backbone of China’s economy but suffer the blunt end of Communist rule. [Source]

Nectar Gan in the South China Morning Post reports on one NGO worker who provides services to Beijing’s migrant population:

The municipal authorities have denied the most recent sweep targets the so-called low-end population of migrant workers and their families, insisting the main goal is to tackle threats from unlicensed buildings.

But the effect has been to force men, women and children onto the street at the start of winter.

That prompted Yang, 43, to swing into action. In March he had opened the drop-in centre called Tongzhou Home, meaning “in the same boat”, providing a range of free services such as movie nights, haircuts and table tennis for migrant workers – all supported by donations from the public.

That night, as he waited for word to spread, Yang was visited by police officers who told him to cease and desist. The officers watched as he deleted the online appeal, returning the next day to tell him to shut down Tongzhou Home. [Source]

Heart-warming to see Beijing volunteers, restaurant owners&others helping migrant workers displaced in govt's latest demolish&evict campaign by providing transport, food, lodging & jobs. May be a small slice of Chinese middle class but gives hope of social change

— 王丰 Wang Feng (@ulywang) November 24, 2017

Some NGOs, even ad hoc volunteer groups, now getting trouble from police & their online messages offering help getting deleted. What a bunch of assholes! https://t.co/L4JCV8OkQ6

— 王丰 Wang Feng (@ulywang) November 25, 2017

A group of over 100 intellectuals and writers issued a public letter condemning the government’s actions. (Read the letter in Chinese.) Legal scholar He Weifang expressed his anger and his support of Beijing’s migrant population in a handwritten note (due to his quitting all social media following persistent censorship of his accounts). Donald Clarke has translated his note:

[…] The development and flourishing of Beijing over the past ten years is utterly inseparable from the hard work done by outsiders and their low-paid contributions. A harmonious city must have the complementarity of people of different income levels. We need fancy shopping malls and also need convenient sidewalk vendors; we need rich people who spend money like water and also need low-income people who are on the go every day to feed and clothe themselves … [Source]

Beijing's migrant workers' mass eviction already affecting China's e-commerce. Note on clothing retailer Semir 森马website stating that express delivery to BJ no longer possible. #nomigrantsnocouriers https://t.co/r2HblwnJBs

— Oliver Lutz Radtke 纪韶融 (@olr_olr) November 26, 2017

https://twitter.com/tianyuf/status/935314689575100416

Everyone DOES realize it's a problem. I've talked to even 官二代 who are upset about it!

— chris xu (@xuhulk) November 28, 2017

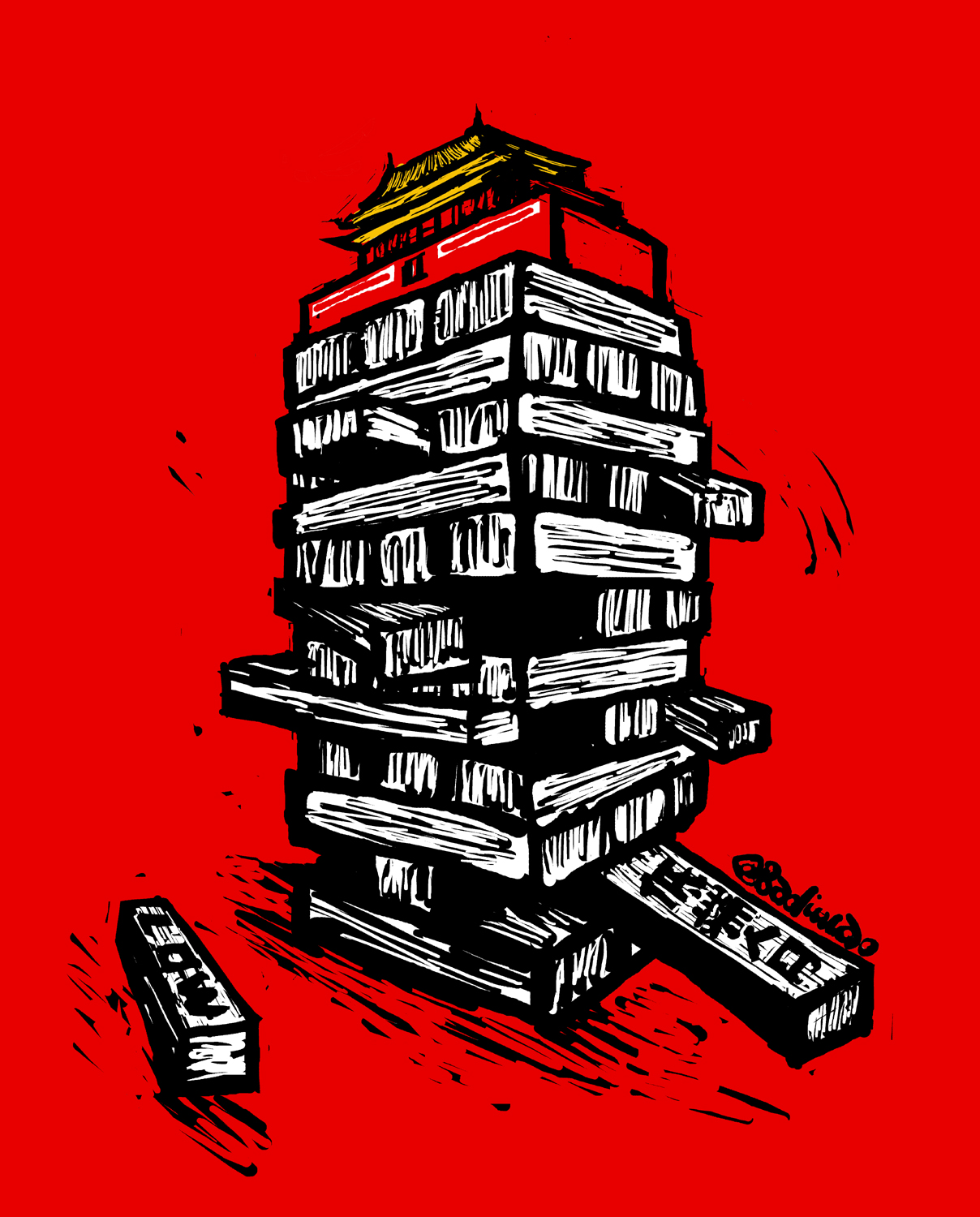

CDT cartoonist Badiucao illustrates the critical role played by migrant workers in the city by showing a pile of Jenga blocks, with the Tiananmen Gate on the top representing the city’s elite. As the block labeled “low-end population” is removed, the whole structure crumbles.

“Low-End Population Building Blocks” by Badiucao:

Migrant workers are not the only ones affected by the evictions, as neighborhoods housing more affluent members of society have also been targeted:

https://twitter.com/YuanfenYang/status/935082557976338433

https://twitter.com/YuanfenYang/status/935083310723862528

https://twitter.com/BeijingPalmer/status/935136672055951360

https://twitter.com/BeijingPalmer/status/935162859750809600

https://twitter.com/BeijingPalmer/status/935186605429493760

https://twitter.com/BeijingPalmer/status/935152954696384512

The evictions in Beijing have been carried out as a scandal involving alleged child abuse at multiple childcare centers, including one for middle class families in Beijing, has erupted, exacerbating public frustration with an apparent lack of official concern for public well-being and safety. Bloomberg reports on the convergence of the two events and its impact on public opinion of the government:

The two incidents show the challenges President Xi Jinping faces after vowing to focus more on quality of life over economic growth in his second term. While authorities keep a tight lid on public dissent, the party’s legitimacy to govern is directly tied to its ability to deliver high living standards — something Xi terms “the Chinese dream.”

“China’s haves and have-nots were both angered in the spate of a week,” said Deng Yuwen, a public affairs commentator in Beijing and a former deputy editor of Study Times, a leading party journal. [Source]

On the Beijing kindergarten scandal: the number of times I’ve interviewed middle class people whose luck ran out and hit China’s lack of rule of law and how gobsmacked they look. Suddenly, human rights matter. Funny how your view changes when it’s you. 🤷🏻♀️

— Melissa Chan (@melissakchan) November 25, 2017