This series is a month-by-month recap of censorship instructions issued to the media by government authorities in 2017, and then leaked and distributed online. The names of issuing bodies have been omitted to protect sources.

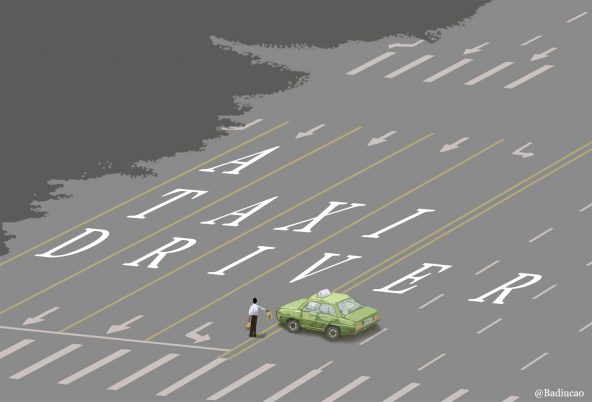

CDT obtained only a single directive in October, following a similarly quiet August and completely silent July after years of gradually slowing leaks. Municipal Cyberspace Administration authorities in Beijing ordered sites to “find and delete all introductions, online encyclopedia entries, film reviews, recommendations, and other articles related to the August 2017 South Korean film ‘A Taxi Driver.’” The film follows its eponymous protagonist and German journalist Jürgen Hinzpeter on the 160-plus-mile drive from Seoul to Gwangju to cover the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, a public response to the violent suppression of student protesters which bears obvious similarities to the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown in Beijing. The film was wildly successful at home and received international critical acclaim, a 95% Fresh rating at Rotten Tomatoes, and a Tiananmen-inspired tribute by CDT cartoonist Badiucao:

A Taxi Driver in 1989, by Badiucao

The real taxi driver’s identity remains uncertain, and his backstory in the film is fictional. Hinzpeter’s role in covering the crackdown is now officially celebrated, however, in line with broader recognition of the event and in sharp contrast with Chinese authorities’ continued treatment of Tiananmen commemorations. President Moon Jae-in, who promised during his election campaign to investigate the 1980 crackdown and memorialize it in the country’s Constitution, saw the film in August: an official told reporters that “the movie shows how a foreign reporter’s efforts contributed to Korea’s democratization. [The president] saw the film to honor Hinzpeter in respect for what he did for the country.” Later that month, an exhibition opened at Gwangju City Hall in honor of Hinzpeter, who died in 2016 and whose hair and nail clippings have been interred at a cemetery for those who died during the Uprising. Mayor Yoon Janghyun paid tribute to “a journalist who, at the risk of losing his own life, filmed the democratic uprising some 37 years ago and helped to spread the truth about the events that unfolded.”

South Korean cinema and its examination of the country’s path to democracy have resonated on Chinese social media in the past. In 2015, Weibo users apparently including actor Zhang Ziyi expressed support for detained rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang using references to 2013 South Korean film “The Attorney,” about rights lawyer-turned-President Roh Moo-hyun. Censors targeted a defiant quote from the film: “The hardest rock is still dead; the most fragile egg still holds life. In the end the rock will become dust, but the life nurtured in the egg will someday soar over the rock.”