The following essay was posted on Weibo by a student from Inner Mongolia, under user name “South Moon” (南的月亮), about her experiences living with and befriending her Uyghur and Tibetan classmates. The Weibo post has since been deleted:

I don’t know what tomorrow will bring, so I’d like to share a little of my personal story.

Before university I studied for a year at an ethnic minority preparatory school, where my classmates consisted of a dozen or so Tibetans, and more than 30 people from Xinjiang. This was the first time I interacted with people from a different culture. My Tibetan roommate’s Mandarin and Sichuan dialect were especially good, and since her family would often send local Tibetan specialties to the school, we’d often enjoy lots of tsampa and beef jerky, or drink loads of butter tea. In the winter, when the school didn’t heat the classroom during cold and wet conditions, several Tibetan classmates would sit in a row covering their legs with long woolen blankets and looking particularly nice and warm.

Since there were so many Xinjiang students they all lived together in a very beautifully decorated dormitory—walls adorned with wallpaper and tapestries, surrounded with curtains. Some classmates also spread a large rug across the floor in complete local style. Every time I’d visit their dormitory and then return to mine, there was a great disparity.

Every year at the school the most magnificent holiday was Eid al-Adha. On that day the Uyghur and Kazakh classmates all wear traditional ethnic dress and head ornaments and visit neighboring classes to offer holiday greetings. The first time I saw them on Eid al-Adha I watched them celebrate from my seat and listened to their festive cheer in the Uyghur language, it all made me very happy. It made me even more happy to see their homemade biscuits, cheese, yogurt, candy, and pastries all gathered together in a pile on a desk, their dorm doors open and everyone—whether or not they observe the holiday—eating, drinking, talking, and laughing with one another joyously.

Back then, I never thought we were different, I just thought that it was extremely interesting to experience it. After I started university I got lucky, again having a Xinjiang roommate, but the circumstances were much tighter. I witnessed her go from never missing a prayer session to being forced to reduce the frequency; from above-board and comfortable worship to sneaky and fearful observance. After the Paris attacks, our teachers and counselors advised them against traveling in the name of safety, saying if someone saw them on the street with their headscarves, that particular look would draw hostility. The leaders also attempted to recruit snitches in our dorm to report on her. We didn’t want to, so everytime they asked we’d just lie—she is no longer praying, no longer wearing her headscarf, no longer reading the Quran. By my junior year, our group made a newspaper. We all had a meeting to discuss some ideas. I asked her: in this country, do you have a sense of self-identity? Do you feel that we are different? Her answers were no, and I don’t think so. She said that while our ways of life are different, we were good friends. In those four years she told me of so many things that happened on her soil that I couldn’t dare to believe, of the internet cutoffs, and of people disappearing. One time, our teacher forced her to take off her headscarf, and when she didn’t the police came to the school. She panicked and was called out. She returned crying, and said “The police told me if I don’t take off my scarf I’ll be expelled. My mother also told me to remove it, that studies are more important.”

I’m also an ethnic minority. Last July I went to Beijing to attend a feminist workshop. At the youth hostel, the boss saw the Mongolian script on my ID card and said “We can’t accept people like you, even hotels won’t let you stay.” I asked him what kind of person? He said “you people, Inner Mongolians, Xinjiang people, Tibetans, the local police station has regulations.” At that time, I didn’t know if these absurd rules were real or not, I found it ridiculous to label citizens and discriminate against normal people. Today I saw the news, and fear that it is true. Before then I didn’t have any awareness of my Mongolian identity, since I’d grown up in a Han-inhabited land, spoken Mandarin, and attended a Han school. But because I’d been born in a certain place, I, honorably, became someone whose living space may be squeezed.

I searched my memories carefully and realized that airports in Inner Mongolia would check your ID card before letting you in, but airports in Xi’an would not. I posted my experience on WeChat Moments, and it resonated with many people. Only then did I learn that some schoolmates from Xinjiang received endless calls from the police when they were staying in a hotel. Some policemen even came to their room, in name of stability maintenance, of course.

How ridiculous is this country? It asks you for your love on the one hand, and stabs you with the other. It says you are family and labels you as the lowest-class citizen at the same time. The scariest experience I had on Weibo was when I posted something about a scholar, and people sent me private messages cursing my family be slayed and be raped by terrorists. I could have held back from reading the comments, but I had trouble not seeing these people as real human beings, and I had trouble understanding where their venom came from.

I saw a picture that JY posted several days ago that says “The death tolls are nothing but statistics if we only look at them as a whole, but every case is heartbreaking if we look at each individual closely.” What’s scary about my experience is also that people don’t treat each other as human beings. They don’t even treat themselves as real human beings. They think of each other as anti-China or “Little Pink” monsters, trapped under labels. They are conceptual enemies to each other. And they refuse to learn about each other as real human beings. They refuse to listen.

I know the climate is a bit harsher now. But within pain there is also hope. Pain lets us remember that we are independent, complete human beings. We are also broken people ripped off of some possibilities. We could only carry on but holding onto each other. We need a bit of determination to stand up by ourselves.

When watching the film Our Time Will Come, I saw a comment saying “There is no macro history. It’s all about people’s private matters.” I’ve always thought this comment is of great wisdom. As history is rumbling by and repeating itself, what is real is the mark it leaves on all of us. It might not be grand or ceremonial, but it doesn’t mean that we cannot participate or that we bear no responsibility. We should be stronger and more brave. You could cry, but don’t be afraid. [Chinese]

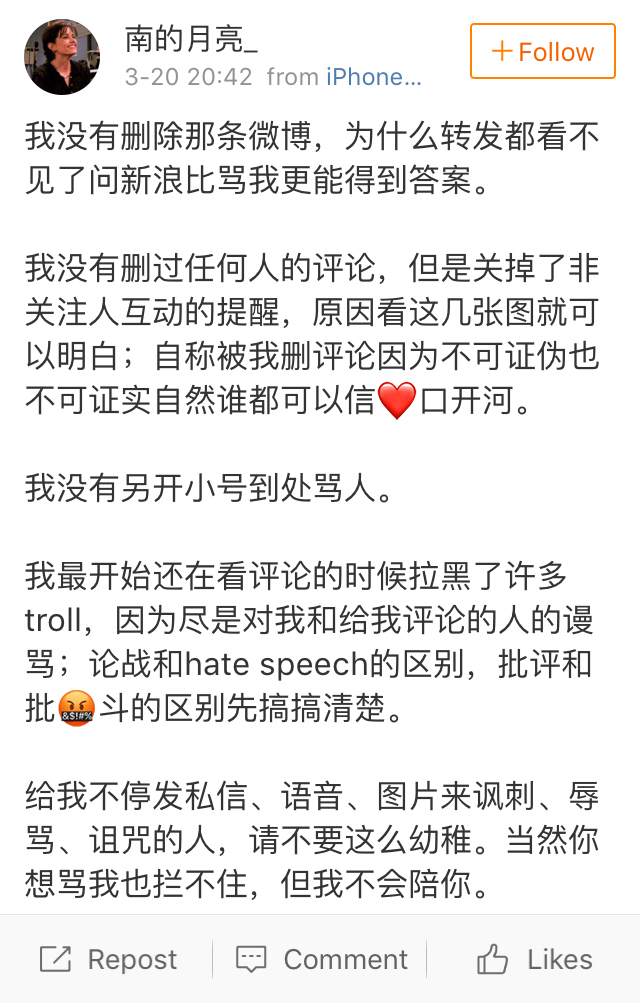

This Weibo post was deleted soon after it was posted. The author later posted another message responding to a barrage of hateful comments she received, calling her, among other things, a “splittist,” a maggot, a monster, and a filthy person. Many readers also accused her of removing the post. She replied:

I didn’t delete that post. You’re more likely to get answers about why reposts aren’t visible by asking Sina than by cursing me.

I didn’t delete anyone’s comments, but I did turn off notifications from people I’m not following. If you look at these screenshots, you’ll understand why. Because there’s no way to prove whether or not I deleted the comments I’m supposed to have done, naturally, anyone can just talk❤irresponsibly.

I didn’t set up any other accounts to curse people with.

At first, when I was still reading the comments, I blacklisted a lot of trolls* because they were just hurling abuse at me and at people commenting to me. First, let’s make clear the difference between debate and hate speech, and between criticism and public denunciation.

To those who’ve constantly sent me private messages, voice clips, and images to mock, insult, and curse me: please don’t be so childish. If you want to abuse me, of course, I can’t stop you, but I’m not going to play any part in it.

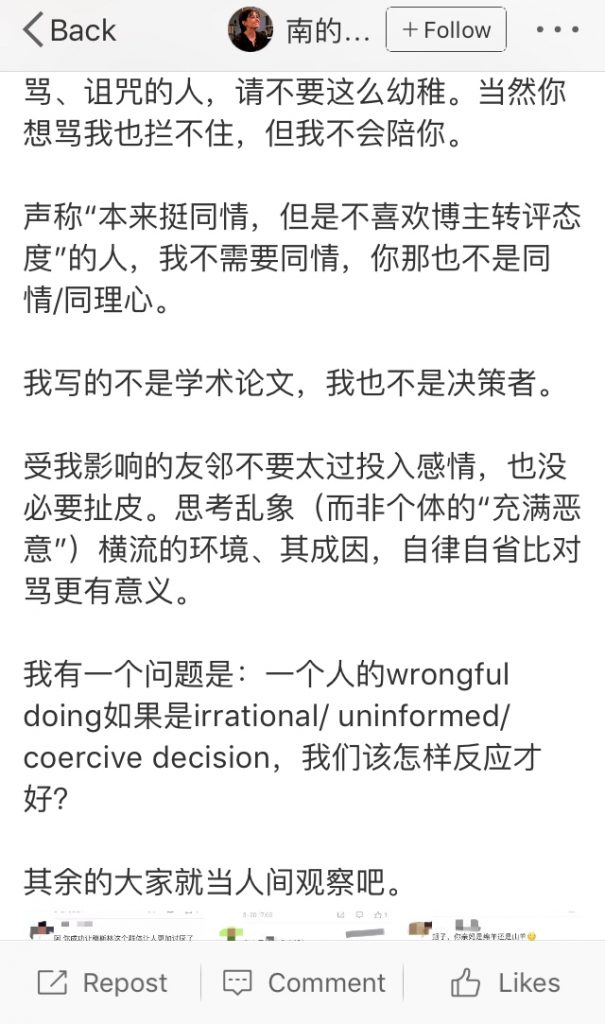

To those who claim that “at first I was sympathetic, but I don’t like the blogger, reposters, or commenters’ attitudes”: I don’t need sympathy, and that’s not real sympathy or empathy anyway.

What I wrote wasn’t a research paper, and I’m not a policymaker.

To those friendly neighbors affected by this because of me, there’s no need to invest too much emotion in it, or to get caught up in arguing. When reflecting on a situation this chaotic (instead of “brimming with malice”), and on its contributing factors, self-control and introspection are more meaningful than slinging insults.

I just have one question: if someone’s wrongful doing is irrational/uninformed/coercive decision, what’s the best way for us to respond?

Just let the rest of it be our social observation.

That post was also deleted.

Translation by Ya Ke Xi, Josh Rudolph, and Samuel Wade, with assistance from Sandra Severdia.

* All italicized words were originally written in English by the author.