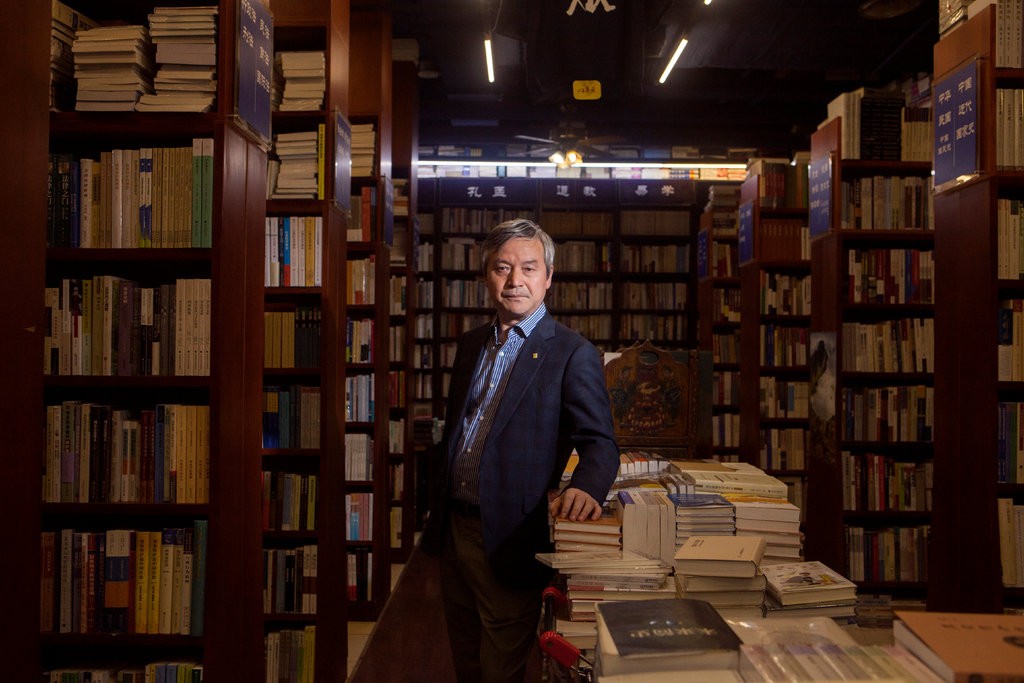

Prominent legal scholar and public intellectual He Weifang has been forced into silence after spending decades advocating for constitutionalism and the rule of law in China. He ended his social media presence last year following repeated attempts by authorities to shut down his Weibo, WeChat, and personal blog accounts after he commented on changes to the civil code to protect the image of martyrs and heroes, which has since become law. At The New York Times, Chris Buckley writes that He’s awareness of the winding historical trajectory of legal and political change in China has prepared him to bide his time and wait for the right opportunity to speak up again.

Mr. He, 57, said life had taught him to take a longer view of the country’s political evolution. His career has followed the twisted path of Chinese liberal reformist hopes over four decades, from the optimistic ferment of the 1980s to the reversals that have accelerated into an avalanche under Mr. Xi.

“Recent developments in China have delivered a big wake-up call to Chinese liberals that nothing will come easily,” he said.

[…] Mr. He emerged in the 1990s as one of China’s most articulate proponents of this legal approach. In 2003, he backed a successful campaign, whose leaders included two former students, to ban the detention and expulsion of migrants moving into Chinese cities who were accused of not having the right permits. The case became a landmark in Chinese hopes of using the law to promote political change.

[…] Since Mr. Xi came to power in 2012, the pressure on Mr. He and other wayward intellectuals has deepened. But he said he was prepared to wait until he would be allowed to roam the country again, giving talks. [Source]

The government’s attempt to silence and sideline He Weifang is in step with President Xi Jinping’s broader aim to curb legal advocacy and roll back freedom of speech and other civil liberties in the country. Rights lawyer Wang Yu, who was the first to be detained in the nationwide “Black Friday” or “709” crackdown on legal activists in 2015, was forced to criticize and reject an award given by the American Bar Association in 2016 in recognition of her dedication to human rights. In a newly released report, Wang described how she was pressured into denouncing the award on national television. From China Change via HKFP:

How, then, did they want me to cooperate? They said all the 709 Crackdown people need to demonstrate a good attitude before they would be dealt with leniently. They said a PSB [Public Security Bureau] boss would come to the detention centre in a few days and they wanted me to say to him that: “I understand my mistake, I was tricked, and I was used. I denounce those overseas anti-China forces and I am grateful for how the PSB has helped and educated me.” After that, they stopped taking me to the interrogation room and moved me to a staff office where they fixed up space for me to eat and memorise the material my interrogator gave me.

[…] In the beginning of July, my interrogator talked to me alone. He said, “Think carefully. If you don’t agree to go on television how will you be able to get out? How will your husband Bao Longjun be able to get out? How will your son ever be able to study abroad?”

I thought hard about it for a few nights. I thought, neither me nor my husband can communicate with anyone from outside. Who knows when it will all end. And my poor son was home without us. We didn’t know how he was doing. Although, my interrogator told me that he had been released and was living in Ulanhot, he might be under surveillance, he didn’t have his parents with him. What kind of future would he have?

[…] So, I decided to accept. I just wanted to see my son so much. I thought, if I couldn’t get out my son would never be able to study overseas. I might get out many years later, but by then what would have happened to my son? If he was harmed now, the trauma would stay with him his whole life. I needed to be with him during this stage of his life. I decided that I would do my best to help my son go to a free country and study. He would no longer live like a slave, suffering in this country. He has to leave, he must leave, I thought. That was the most urgent thing. So I had to do it, even if it meant doing something awful. [Source]

Elsewhere, a Hong Kong journalist has been released after he was detained in Beijing earlier this week while covering the hearing of human rights lawyer Xie Yanyi. Sum Lok-kei at South China Morning Post reports:

Chui Chun-ming, a cameraman for Now TV, was released at 1pm after being hauled away at about 9am. The State Council’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office had “mediated” at the request of the Hong Kong government.

Speaking to Hong Kong media after his release, Chui said he was made to sign a “statement of repentance”.

[…] Chui and other crew members were covering a Beijing Lawyers Association hearing that involved human rights lawyer Xie Yanyi on Wednesday.

The Post understands the hearing related to Xie’s past work defending Falun Gong practitioners. Xie was one of the lawyers arrested in the “709 crackdown” of 2015, during which the Chinese government arrested about 300 lawyers and activists. [Source]

Rights Lawyer Ding Jiaxi was prohibited from boarding a plane to visit his family in the U.S. after authorities cited national security reasons for the travel ban. Ding was involved in the New Citizens’ Movement that called on Chinese officials to publically reveal details of their wealth. He was detained in April 2013 and handed a prison sentence a year later by Beijing’s Haidian District People’s Court for “gathering a crowd to disrupt public order.” From Radio Free Asia:

Ding Jiaxi, who has previously served jail time for calling on top officials of the ruling Chinese Communist Party to reveal details of their wealth, was stopped by police at Beijing International Airport on Thursday as he tried to board a plane to visit his wife and daughter in the U.S.

Ding said he was at the departure gate on Thursday, preparing to board the aircraft, when he was approached by two unidentified officers.

“Two of them came over and announced to me that they had a notification from the Beijing police department that I was a threat to national security, and I was to be prevented from leaving the country,” Ding told RFA.

“At no point during this process did they tell me their names, nor did they show me any official ID,” he said. “They also refused to give me the notification in writing.” [Source]