After successive waves over the past year, China’s #MeToo movement against sexual assault and harassment has flared up again with a series of accusations against prominent male activists, media figures, and most recently a senior Buddhist abbot. A pair of leaked directives published on Tuesday ordered sites not to “hype” related content, with particular emphasis on the case of star state broadcaster host Zhu Jun.

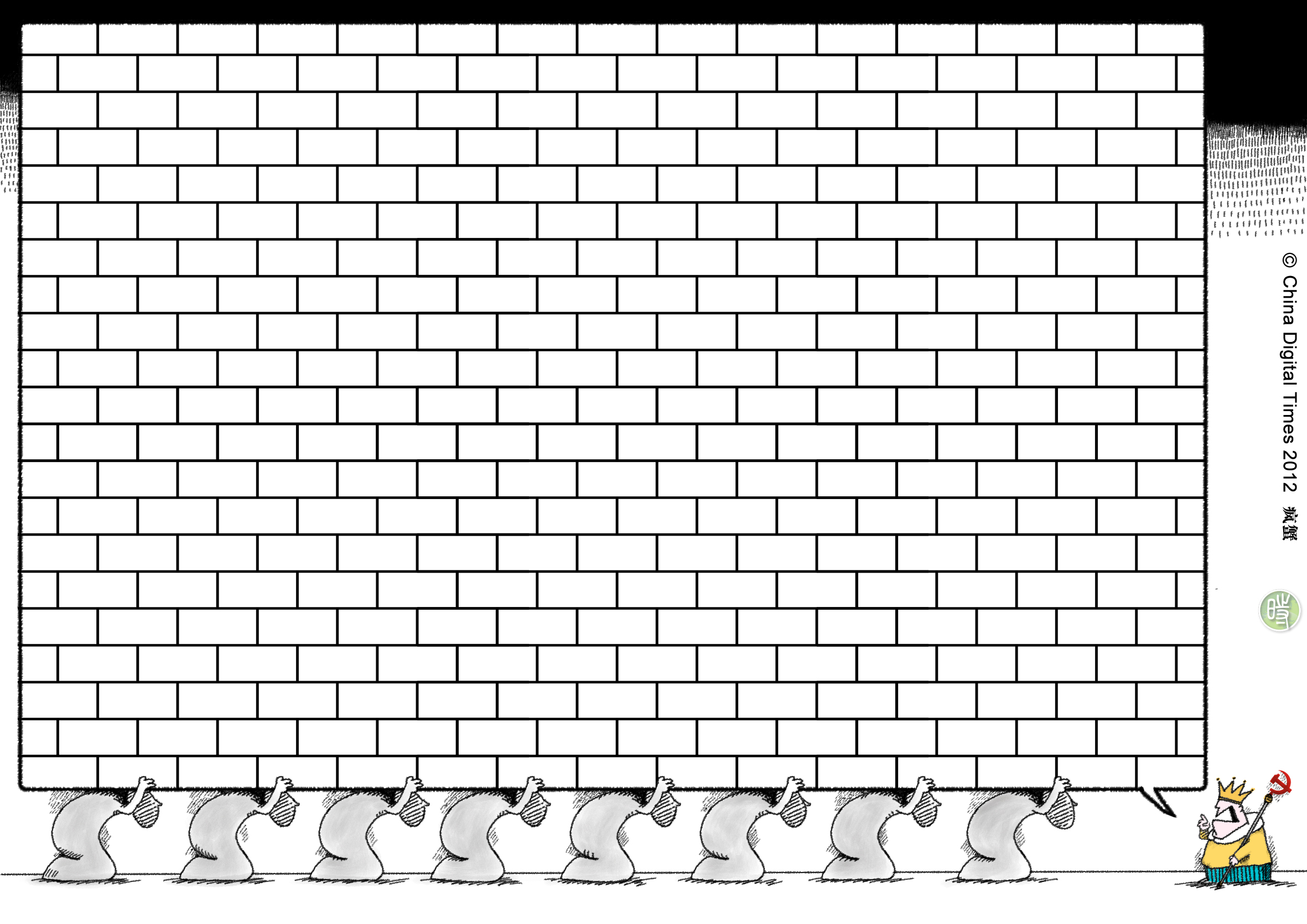

Last week, CDT translated a lengthy response to recent cases by one of China’s leading feminist activists, Li Maizi, on the need for greater awareness of gender issues across Chinese civil society. In another, shorter recent essay, writer Mo Zhixu comments on the need for his fellow male activists to confront their dual roles in resisting one form of oppression while participating in another. He cites an earlier piece written by journalist Chang Ping in 2015, titled “We Can’t Pretend We’re Not Bricks In The Wall.”

Mr. Chang Ping used this title, and I pay tribute here because I can’t say it any better. In a totalitarian society, men and women are both stripped of their rights. But in terms of social construction, totalitarian and patriarchal societies have much in common. A man in a totalitarian society has a dual status: at once both deprived of his rights and endowed with a sense of social superiority.

As a result, a paradox can arise in which a man is the resister, the downtrodden when he opposes totalitarianism and pursues freedom and democracy, but becomes the oppressor, the social stability maintainer, when it comes to matters related to gender. As Chang Ping put it, “I know clearly that in a totalitarian society, every man is born as a member of the patriarchy. Patriarchy is the foundation of this society, shaping our livelihoods, our thought and language, the rules of our society, and our professional achievements. If we reject it, we must start again from scratch. People, especially men, therefore want to maintain stability on its behalf.”

The problem is that the goals of gender equality are in fact precisely a part of, or an extension of, those of equal rights: to put it simply, rights mean an individual’s personal autonomy in relation to various authorities— this is more or less equal to their freedom. Equality means the individual’s likelihood of engaging in all kinds of affairs. Together, these constitute the foundation of a democratic system. Gender equality is in fact integral to equal rights/freedom and democracy as a whole, to the extent that, as Chang Ping puts it: “feminism saves China. On one hand I find it hard to imagine, in the modern world, what kind of legitimacy democracy could have without gender equality. On the other, feminism’s analysis of power structures helps us better understand autocracy. If we reflect a bit on how we treat women’s rights, we can understand how those in power treat human rights.”

The current #MeToo movement is not at all a matter of moral rectification, but rather of a kind of collective resistance to structural male social power. Of course, this also includes resistance to a dictatorial system that tramples on basic rights. To think of it only as a moral appeal, therefore confining it to the private sphere, is to overlook its public aspects, and in many cases to join in with the authorities’ various existing forms of suppression of women. These have also taken root in all aspects of social convention, custom, and even language and culture. None of these are subordinate to the private sphere, and their resolution requires not only conceptual, moral, and cultural reform, but corresponding political, legal, and social transformations.

Thus, when someone who pursues freedom and democracy simultaneously harbors unacknowledged views or behaviors regarding gender equality, then their own pursuit in fact becomes contradictory, or at least incomplete. For those like Chang Ping and I who’ve spent the greater part of our lives in a patriarchal culture pursuing freedom and democracy, to be on the receiving end of advocacy for equal gender rights can of course take us out of our comfort zones, but as long as we recognize the common ground between the two sides, we should not reject this advocacy.

Even if this advocacy constitutes an attack on our own past behavior, and reopens old wounds, I’m afraid there is no choice but to honestly confront it. Speaking for myself, I’ve had many drunken indiscretions. If these are brought to light, I understand that this is not merely a matter of moral image: this kind of past behavior is the greatest affront to my own actions in pursuit of equal rights, freedom, and democracy. If I still can’t honestly face it, it can only make a joke of my pursuit.

Our own pursuit of the values of freedom and democracy takes place in a time of deep change for the whole of society, including in terms of gender relations. As we don’t have the benefit of foresight, it’s very likely we will get caught up in our own difficulties. These difficulties certainly do not rest upon a small minority or even a handful of people. But the best way to resolve them can only be to let everyone take it upon themselves.

Under totalitarianism, China’s #MeToo movement is in fact pushed forward by a few people on the relative margins. It’s only because its volume was magnified in this social media era that it could attain this rare and perhaps short-lived influence. There is no way that its fundamental ideas and positions will be understood by society at large anytime soon, let alone accepted. But for intellectuals and activists who’ve long carried the ideals of freedom and democracy, it should not be hard to understand and support the #MeToo movement. Still less should they, like certain men, fall in line with the “online mass criticism” and go so far as to launch an “online Cultural Revolution.”

Limited by the environment in which we’ve grown up, we old men might find it difficult to cast off many restrictive notions, and still more so to detach from existing networks of reputation and interests. But it’s not too difficult to understand the connections between gender equality and the equal rights we’ve long advocated. It just requires a kind of empathic conclusion: when you and I suffer under the dictatorship’s pressure, please don’t forget that when it comes to the gender power structure in an unequal society, you’re also another brick in the wall. [Chinese]