Minority languages in China are increasingly under threat. Over the past week, the language learning app Talkmate and the online video streaming site Bilibili appeared to remove Tibetan and Uyghur languages from their platforms as a result of government policy, while continuing to allow Mandarin Chinese and numerous foreign languages. The move reflects the CCP’s shift toward a more assimilationist stance on linguistic and ethnic diversity.

On Friday, Talkmate’s Weibo account announced that Tibetan and Uyghur courses were indefinitely removed due to “government policies.” By Monday, the post itself was no longer available. Ironically, Talkmate prides itself on having been “selected by UNESCO to become the only application platform of World Atlas of Languages to promote […] multilingualism and linguistic diversity worldwide.” Its partnership, which dates back to 2016, was updated ahead of the 2019 Year of Indigenous Languages. A UNESCO news brief on the partnership described Talkmate’s commitments and goals:

The joint partnership between UNESCO and Talkmate on the World Atlas of Languages aims at developing an innovative and scalable ICT-supported platform to access data on linguistic diversity around the world. This partnership is not only contribute to the promotion of languages learning via the cyberspace, but also encouraging the collaboration of stakeholders to raise awareness on the importance of multilingualism by the effective application of ICTs, which are vital educational and communicational tools that help communities and organizations to access education, share information, provide services and goods, to which citizens are entitled in the context of open, pluralistic, participatory, sustainable and inclusive knowledge societies.

In a long-term the partnership will contribute to fulfil the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development as a whole, to ensure a multilingual cyberspace by the effective application of ICTs, which are vital educational and communicational tools that help communities and organizations to access education, share information, provide services and goods, to which citizens are entitled in the context of open, pluralistic, participatory, sustainable and inclusive knowledge societies.

UNESCO, together with Talkmate, is committed to safeguard the world´s diverse linguistic, cultural and documentary heritage. [Source]

It seems that today there has been a realatively widespread crackdown on Tibetan and Uyghur scripts on the Chinese internet today, with Bilibili and Talkmate both removing/banning the languages, I suspect there are several more apps doing the same. https://t.co/z2LfVNGSeL

— Nathan Ruser (@Nrg8000) November 1, 2021

Bilibili revealed similar signs of censorship. On Monday, users appeared unable to comment on videos using Tibetan or Uyghur script, while languages such as Hebrew, Russian, Thai, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese were permitted. When one user tried to use Tibetan or Uyghur, the resulting error message read “评论内容包含敏感信息” (“Comment content contains sensitive information”), which commonly refers to politically-sensitive content. Bilibili’s previous history of censorship includes suppressing certain LGBTQ+ content deemed “inappropriate” in 2018, after sharp criticism from regulators for hosting “vulgar content.”

Nasdaq-listed Chinese video platform Bilibili @bilibili_en has seemingly banned Uyghur & Tibetan.

I was just able to post "Interesting" in English & Mandarin, but Uyghur or Tibetan wasn't allowed.

Error message = "评论内容包含敏感信息" (Comment content contains sensitive info) pic.twitter.com/MMCQgOVYH4

— Fergus Ryan (@fryan) November 1, 2021

CDT translated several netizen reactions to the bans on Reddit:

Lubiaoyang: We respect minority cultures. Derp.

True-Pension5772: Come on, we printed those minority languages on the yuan, didn’t we? /s

Madazuo: Why don’t you look at how America wiped out its indigenous peoples? Which is more humane: killing them or erasing their languages?

Accomplished-Cat8996: Why don’t you look at how humans wiped out mammoths? [Chinese]

The suppression of China’s minority languages is the result of increasingly assimilationist government policies. In January, Shen Chunyao, head of the National People’s Congress’ Legislative Affairs Commission, stated that the use of minority languages in classrooms was “incompatible with the Chinese Constitution,” despite article four of the constitution guaranteeing all ethnic groups the “freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages.” In September, the National Ethnic Affairs Commission’s childhood development policy draft omitted that guarantee of language freedom and replaced it with the phrase “promoting the common national language.” Assimilationist policy changes regarding minority languages demonstrate the arrival of “second-generation ethnic policies,” which promote ethnic unity over diversity and are being formally rolled out on a nationwide level.

In this tightening political climate, use of the Uyghur language has been particularly dangerous, as the CCP campaign against the “three evils of terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism” conflates linguistic and cultural expression with national security threats. In the network of mass internment camps that have reportedly housed over one million Uyghurs, detainees are forced to undergo intensive Mandarin language classes. Authorities have targeted and detained numerous Uyghur writers, translators, poets, and intellectuals in these camps, where some have subsequently died. In some cases, Uyghur books have been blacklisted and removed from bookstores, and Uyghur textbooks have been banned and their authors arrested for inciting terrorism. Authorities have banned the Uyghur language in certain Xinjiang schools and sent an estimated 500,000 Uyghur children to state-run educational institutions, where some children have faced physical abuse for speaking Uyghur instead of Mandarin.

Despite heavy censorship, some internet users still find ways to share their experience of the current state of ethnic languages in China. A Han Chinese tourist who traveled to Xinjiang earlier this year noticed the lack of indigenous scripts in some regions:

Outside Kashgar, you can hardly see traces of indigenous culture on the storefronts. When we arrived in Ghulja, our travel buddy from Tieling [a city in Northeast China] made a joke: “Welcome to the melting pot of Sichuan and Dongbei.” Sichuanese restaurants were everywhere; so were the grayish or yellowish buildings that looked similar to those in Dongbei. There were rows upon rows of chain stores such as Dicos, Miniso, Chabaidao and other knock-off brands.

Upon entering a tea shop, I tried to crack a joke with a Han Chinese shop assistant and asked why there were no Kazakh characters on the store sign. The staffer suddenly became serious and answered me in a raised voice: “We are all Chinese people. Why should we use two different languages?” I was taken aback and not sure how to respond. [Chinese]

The Tibetan language has also suffered under state policy. The growth of bilingual education has sidelined Tibetan in favor of Mandarin and raised concerns at the UN. Public signs and banners have officially imposed Chinese characters above Tibetan script, reversing a norm dating back to the 1980s. In 2015, Tibetan language-rights activist Tashi Wangchuk was arrested on charges of separatism, allegedly tortured during his two-year pre-trial detention, and remains under official surveillance since his release in February 2021.

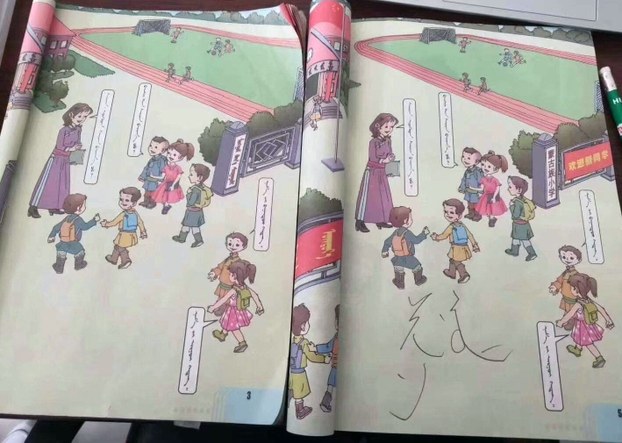

Mongolian is another minority language under threat. Authorities cracked down on a wave of protests across Inner Mongolia in late 2020 over proposed language education reforms that would gradually replace Mongolian with Mandarin. To silence the popular unrest, local governments shut down over 70 Mongolian WeChat groups, suspended Mongolian-language online social networks, detained at least 23 people, and offered rewards for identifying suspected protesters. In early 2021, state media allegedly began replacing Mongolian content with Han Chinese cultural content in a campaign whose official slogan is “Learn Chinese and become a civilized person.” CDT Chinese has published numerous examples of how increasingly restrictive language education policies in Inner Mongolia are gradually transforming the materials used in classrooms:

Caption: In the original textbook (at left), the signs on the school gate were written in Mongolian script. In the new textbook, the signs on the school gate are written in Chinese script. (Source material: from volunteers / Editor: Qiao Long)

Caption: Mongolian textbooks deleted nationalist poems about Mongolian people’s love of their hometowns, culture and mother tongue. (Twitter screenshot provided by Qiao Long.) [Source]

Alex Yu contributed to this post.