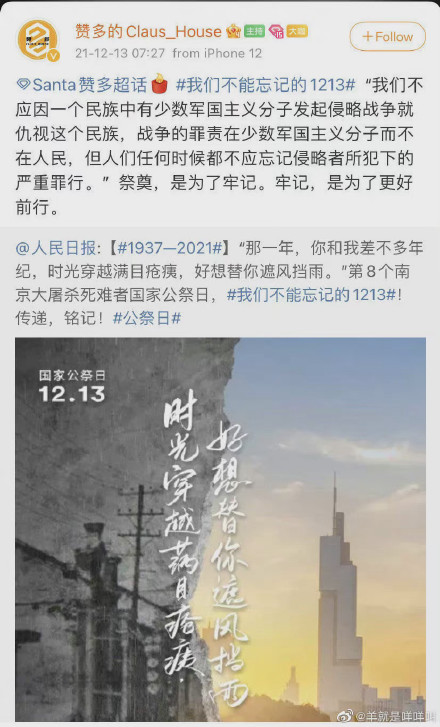

On December 13, the moderator of a Weibo supertopic page dedicated to Uno Santa, a Japanese member of a Chinese boy band, reposted a People’s Daily commemoration of the Nanjing Massacre and added the caption: “‘We should not despise a nation because a small cadre of militarists in their midst instigated an invasion. Those few militarists are guilty of war, not the people. Yet at no time should we ever forget the serious crimes of the invaders.’ We mourn so that we may remember. We remember so that we may better move forward.” The moderator, @赞多的Claus_House, immediately came under attack by little pinks—understanding why (and why the little pinks’ onslaught was folly) offers a snapshot of the mood on the Chinese internet.

The post that inspired so much controversy.

Nationalists immediately heaped vitriol on @赞多的Claus_House for supposedly excusing Japan’s World War II atrocities: “Race traitor,” “Japanese devil,” “What right do you have to forgive on behalf of our ancestors?” “You idolize pop stars so much you’ve lost your mind.” The outburst captures an interesting phenomenon: fan culture and nationalism often intersect, increasingly so after the state initiated a clean-up of the “chaos” in China’s online fan culture earlier this year. Over 100 fan groups (such as the one for Uno Santa) suspended their normal activities on the National Memorial Day for Nanjing Massacre Victims. Many online fan groups copied and pasted the same message: “On this special day when we respect the dead and mourn our compatriots who died during the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, please do not publish entertainment content related to celebrities on online platforms.” Many e-commerce and social media platforms temporarily changed their home pages to black-and-white in a digital memorial, perhaps for the first time ever:

Some of China's biggest ecommerce and streaming sites are now switching from color to black and white mode to commemorate the Nanjing Massacre that started December 13, 1937. pic.twitter.com/6dB3PnZaNt

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) December 12, 2021

It is new to me, and since it's a hashtag on Weibo now with people discussing it I do think it's the first year this happens.

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) December 12, 2021

Amidst the frenzied atmosphere, none of the little pinks attacking @赞多的Claus_House noticed a crucial detail: the Weibo post was a quote. But from whom, exactly? As Weibo user @jakobsonradical later pointed out, the quote came from none other than Xi Jinping, in a 2014 address commemorating the massacre:

The quote was featured in a 2019 Xinhua compilation under the headline, “Lest History Be Forgotten: Powerfully Resonant Quotes from Xi Jinping.”