With the 25th anniversary of the 1989 protest movement and subsequent crackdown, many observers are reflecting on how those events have helped shape China over the past quarter century. How did decisions made by Deng Xiaoping and other leaders at the time change China’s course? And how are current policies a response to events 25 years ago? Columbia University professor Andrew J. Nathan writes that 1989 marked a moment of choice for China’s leaders:

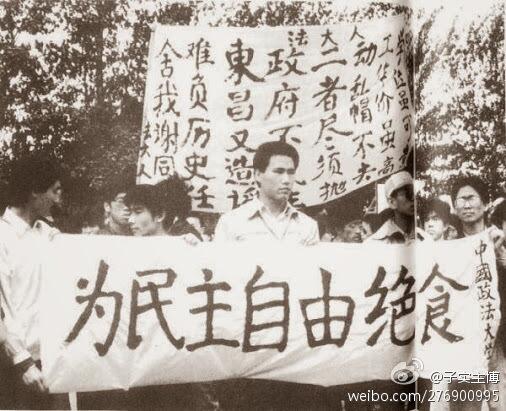

The regime’s attack on the pro-democracy movement in Tiananmen Square was an inflection point, one at which it could have chosen liberalization or repression. Zhao Ziyang, who was the leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), favored dialogue with the students. He argued that they were patriotic, that they shared the regime’s goal of opposing corruption, and that if the leadership told the students that it accepted their demands the students would peacefully leave the square. Li Peng, the prime minister, countered that if the CCP legitimized opposition voices by negotiating with them, the party’s political rule, based on a monopoly of power, would crumble. In the end, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping sided with Li.

Having picked the path of repression in 1989, the regime has had to steadily step it up. Here, too, the May 3 meeting is emblematic. The participants were calling for the regime to acknowledge that the student demonstrations were not dongluan, “a turmoil” — the official term for the demonstrations, which implies that they were a violent rebellion. They also requested that the government acknowledge that its killing of people in the square was a mistake, absolve those who had been convicted in connection with the protests, and identify those killed and offer compensation to their families. Such demands are not exactly radical, but they fly in the face of the government’s preferred method for dealing with 1989: forgetting it. Even today, the regime is unable to hold a dialogue with citizens on this or any other substantive topic for fear of losing control. [Source]

Lessons from 1989 made it clear to many that, once the decision to crack down on protesters was made, political reform was no longer an option to be discussed. As Verna Yu reports for the South China Morning Post:

An elderly former official, speaking anonymously out of fear of reprisal, says many people learned after Tiananmen that “if you rely on Deng [Xiaoping], there is no hope for democracy and freedom. Only dictatorship will continue”.

After the protest was suppressed, political reform became taboo. Deng, however, insisted that market reforms continue. Those changes fuelled stellar economic numbers and prosperity for many as the economy grew to be the world’s second largest.

But without checks on official power, it spawned unbridled corruption, one of the widest rich-poor gaps in the world and social discontent, analysts say.

“Corruption … is made much worse in an authoritarian system where there are no independent checks on power – free press, independent courts, independent NGOs,” says [Perry] Link.

Despite the problems it has brought, including rampant corruption, current leaders are sticking firmly to the path chosen by their predecessors, according to Edward Friedman in the China Policy Institute blog:

CCP ruling elites in the PRC are persuaded that paramount leader Deng Xiaoping did the right thing when he ordered the CCP’s military to crush China’s spring 1989 popular, nationwide democracy movement on June 4. The Beijing Massacre supposedly allowed the CCP’s leftist conservatives, at least after January 1992 when Deng defeated anti-economic reformers, to rise and amass the wealth and power which allows the PRC to use coercive diplomacy to assert its political will on behalf of extraordinary territorial claims all over Asia, especially in maritime territories.

The result of June 4, in contrast to August 1991 in the USSR when the Soviet Union imploded and the CPSU was toppled, is a confident, expansionist PRC in international relations and a paranoid politics at home. To avoid what happened to the Soviet Union, a paranoid CCP cruelly crushes societal efforts by Chinese to improve life and dignity for the Chinese people. The victims range from Uyghurs seeking to preserve their culture to Han seeking to move China away from the pains caused by greedy, self-serving, corrupt CCP networks which treat Chinese efforts for justice and fairness as existential threats to the CCP. Courageous Chinese working for justice today must, in the mind of the paranoid CCP, be destroyed, as Deng destroyed Chinese democracy supporters in 1989. [Source]

According to Ellen Bork in the Daily Beast, quoting Perry Link, the events of 1989 lay the groundwork for the current dynamic between the Chinese populace and government:

Anniversaries are typically backward-looking affairs, but for China, the events of 1989 are intimately linked to the future of Communist Party rule. After Tiananmen, writes Perry Link, a China scholar and an editor of a collection of leaked Party documents about the crackdown, China’s paramount leader Deng Xiao-ping embarked on “a systematic effort to extinguish [people’s] political longings and to mold them into ‘patriotic’ subjects focused on nationalism and money.” Mao’s brutal ideological campaigns of the 1950s and ’60s may have been more damaging, according to Link, “but Deng’s formula for the Chinese people of ‘money, yes; ideas, no’ … laid the foundation for so much of what we see in China today … ethical deterioration … fear … dread … [and] intimidation.” [Source]

Despite economic gains, the failure to allow discussion of the past, rather than securing the government’s hold on power, is threatening its legitimacy, according to Elizabeth Economy in USA Today:

Collective memory is powerful. Beijing must already contend with a continuous trickle of tortured personal accounts by those who participated in the upheaval of the Chinese Cultural Revolution more than four decades ago. Tiananmen, while much briefer in duration, is far more recent and, thanks to the presence of the foreign news media, was witnessed by more of the world than the Cultural Revolution. No matter how hard Beijing tries to ignore or revise its history, the facts are there for the world to see.

The result is that Beijing is stuck. Even as China has transformed into a global power through its economic achievements and growing military prowess, Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Communist Party’s ambitions for legitimacy at home and abroad remain mostly unrealized. Within China, the party’s mad dash to legitimize itself in the eyes of the Chinese people through anti-corruption efforts, self-criticism and attempts to “learn from the people” all fall short in the face of the party’s refusal to deal with its own history.

How can the people’s trust be granted to a leadership that cannot acknowledge past mistakes? [Source]

And while the explicit violence of June 4th has not been repeated, Elizabeth Lynch argues on her China Law and Policy blog that the repression of dissenting views is just as severe today as it was in 1989, but is manifested differently:

No longer is its violence against dissent as public as it was the morning of June 4, 1989. And no longer does the CCP come off as a lawless regime. Instead, its cloaks its crackdowns with a veneer of legality. Since April 2014, in preparation for the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, the Chinese government has detained – either criminally or through unofficial house arrest – over 84 individuals. But these individuals are not detained under the guise of being counter revolutionaries like the students of the 1989 movement. That would be too obvious. Instead, the Chinese government has slapped the vague and overly broad crime of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles.” After 20 years of Western rule of law programs, the CCP has come to realize that the easiest way to deflect global criticism is to follow legal procedure, no matter how abusive, vague or entrapping that legal procedure might be.

If the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen means anything, China’s new strategy – the use of law to suppress dissent – must be examined and criticized. China’s activists are being violently detained and imprisoned in record numbers “in accordance with the law.” But that suppression of dissent is no different than what happened in 1989. It is another method of killing the chicken to scare the monkeys – ensuring that the violence against a few “troublemakers” teaches the rest of society not to rock the boat. This time though the rest of the world is increasingly complacent. [Source]

John Garnaut of The Age notes that many of China’s highest-profile political activists today got their start during the 1989 protest movement. He interviews Pu Zhiqiang, who was detained in May after attending a private symposium on 1989, about how and why he now works within the system to effect change:

His tone changed when he placed his jar of green tea on the table, next to my recorder, and talked through the calculus of when to step outside the line:

“You must see that sometimes it can feel too dark to achieve anything. But you can also see more and more people using law as a tool to defend their dignity, property, land and rights.

“…I will speak the facts and let journalists write so that there will be more and more pressures on individual cases and the people will see there is a way for them to get relatively fair treatment and handle issues without bribing judges with money and sexual opportunities. I am focused on the process as well as the result. The process is a process of raising awareness about human rights.

“No matter what, we must not lose confidence in justice and human nature. We believe this will overwhelm the leviathan. Our aim is not to knock it over but to ensure a peaceful transition after its fall. Even when the ghost of communism evaporates, society still needs to move forward. We can’t afford another revolution. [Source]

* 25 years later, Tiananmen Square still colors U.S.-China relations, by Tom Malinowski, assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor, in the Washington Post.

* Why Tiananmen still matters, by Carrie Gracie of the BBC

* How The Chinese Communist Party Turned Tiananmen Square To Its Advantage, by Matt Schiavenza, in International Business Times

* 25 Years On, Can China Move Past Tiananmen? a ChinaFile discussion

Also see CDT’s Xiao Qiang join Louisa Lim, author of People’s Republic of Amnesia, on Newshour to discuss how June 4th still resonates in Chinese society. Both Xiao and Lim also joined Orville Schell for a discussion at the Council on Foreign Relations.