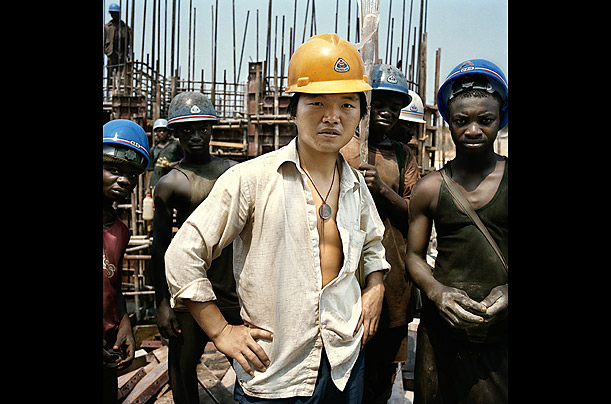

Beijing continues to prioritize China-Africa ties, especially in investment, with Xi Jinping recently pledging another $60 billion in new projects at the triennial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). However, in recent months, there have been increasing concerns about Chinese companies’ racist and discriminatory practices. These include Kenya deporting a Chinese motorcycle trader for his racist diatribe against Kenyans as “monkeys,” and reports that Kenyans working on the debt-saddling $4 billion Standard Gauge Railway were underpaid and subject to unspoken segregation practices. These increasingly widespread claims of racism and worker mistreatment have left many wary of China’s growing presence. Joseph Goldstein at the New York Times reports:

“They are the ones with the capital, but as much as we want their money, we don’t want them to treat us like we are not human in our own country,” said David Kinyua, 30, who manages an industrial park in Ruiru that is home to several Chinese companies, including the motorcycle company where Mr. Ochieng’ [man who filmed the motorcycle trader’s remarks] works.

[…] Other Kenyan workers explained how their office bathrooms were separated by race: one for Chinese employees, the other for Kenyans. Yet another Kenyan worker described how a Chinese manager directed his Kenyan employees to unclog a urinal of cigarette butts, even though only Chinese employees dared smoke inside.

[…] The experience of Mr. Ochieng’ and other workers speaks to the future of relations between the two countries. He took a job as a salesman, thinking it would secure a prosperous future, but when he showed up to work he found a different reality. The pay was a fraction of what he was initially offered, he said, and it was subject to deduction for a long list of infractions.

“No laughing,” was one of the injunctions printed in the company rules. Each minute of lateness — sometimes unavoidable given Nairobi’s notorious traffic — came with a steep fine. An employee who was 15 minutes late might be docked five or six hours’ pay, he said. [Source]

Strained ties are especially apparent during election seasons across the continent. At the Washington Post, Professor Richard Aidoo cites several examples and delves into causes of anti-China sentiment:

1. African elections are essentially about the economy, and China is a significant economic player.

[…] Opponents can blame the incumbent’s willingness to accept an expanding Chinese economic influence that fails to address the country’s economic woes — but if they win, they may decide to follow through with their anti-China pronouncements, or not. Recently, newly installed President Julius Maada Bio of Sierra Leone canceled a Chinese-funded airport project signed by his predecessor, after referring to Chinese projects as “a sham” during a campaign debate.

2. African economies are largely extractive, and China is heavily engaged in this sector.

[…] As extractive sectors are often at the core of African economies, foreign involvement or domination of such sectors can easily elicit popular discontent. China’s increased interests in these sectors no doubt sparks intense political debates, especially when there are reports of mistreatment of local mine workers or increased Chinese involvement in unregulated mining activities. Sociologist Ching Kwan Lee, for example, details the hardships of Zambian mine workers in Chinese-owned mines, which explains the anti-China popular fury that fueled Michael Sata’s victory in 2011.

[…] 3. China has flooded African markets with poor-quality products.

A 2016 Afrobarometer survey of 35 African countries indicated an average of 35 percent of respondents perceived the quality of Chinese products in Africa as problematic for China’s image. Despite the benefits of providing cheaper options of products to African consumers with meager incomes, consumers don’t want to see substandard materials in infrastructure building, or risk purchasing fake pharmaceutical products.

And some African politicians often like to remind voters that cheap Chinese textiles and other goods compete with local products. [Source]

Beijing has also focused on extending soft power into Africa via cultural initiatives such as Confucius Institutes and exporting domestically produced television content. However, it has also converted financial muscle into political muscle by pressuring media censorship and strict academic controls. Geoffrey York at the Globe and Mail reports:

At a major South African newspaper chain where Chinese investors now hold an equity stake, a columnist lost his job after he questioned China’s treatment of its Muslim minority.

In Zambia, heavily dependent on Chinese loans, a prominent Kenyan scholar was prevented from entering the country to deliver a speech critical of China. In Namibia, a Chinese diplomat publicly advised the country’s President to use pro-China wording in a coming speech. And a scholar at a South African university was told that he would not receive a visa to enter China until his classroom lectures contain more praise for Beijing.

Mr. Xi’s promise to African leaders in early September was the latest reiteration of a frequent Chinese boast: a non-interference pledge that often wins applause from a continent with a history of Western colonialism and conditional World Bank loans. China routinely touts its financial engagement with Africa as a “win-win” situation for both sides, in contrast to exploitative Western policies.

[…] One of the most obvious examples is the increasing isolation of Taiwan. Three years ago, four African countries still gave diplomatic recognition to Taiwan, to the displeasure of Beijing. Today, three of those four countries have switched to Beijing’s side, lured by Chinese aid. Only the tiny kingdom of eSwatini (formerly known as Swaziland) still supports Taiwan. [Source]

Against this backdrop, President Trump signed into law a bill that would create the United States International Development Finance Corporation, which will provide $60 billion in loans, loan guarantees, and insurance to companies willing to do business in developing nations. Glenn Thrush at the New York Times argues Trump’s new support for foreign aid is chiefly motivated by the desire to counteract China’s investment projects worldwide:

The new bipartisan push to increase foreign aid began under the Obama administration, but it was rebranded as a means of competing with China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” which has a goal of distributing $1 trillion in construction aid and investments to over 100 countries.

[…] [China’s] investments have raised concerns that poor and emerging nations like Djibouti and Sri Lanka could be increasingly beholden to China, which can seize local assets if countries default on loans.

[…] “If a country can’t pay, they will take assets they want,” [Derek M. Scissors, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute] added. “But they aren’t setting a debt trap. This is about expanding their reach and exercising passive power.”

[…] The new agency will supplant the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, established in 1971 as a lending facility to encourage American companies to invest in developing countries, and will have twice its overall lending capacity. The new entity, like the old, is funded primarily through fees, and will provide loans, loan guarantees and political risk insurance to companies willing to take the gamble of investing in developing countries.

[…] Significant questions remain about how the fund will operate in its new expanded form. The key to its success, development officials said, is to create a new system that will carefully vet investments for maximum economic and political impact — and to ensure that projects don’t fail as a result of corruption and mismanagement, a problem that has plagued China’s investments in Malaysia and elsewhere. [Source]

For more on China’s rising global influence, listen to NPR’s special series China Unbound, and read a MERICS report on how Chinese scholars are questioning Western ideas and discussing how China will lead a potential new global order.