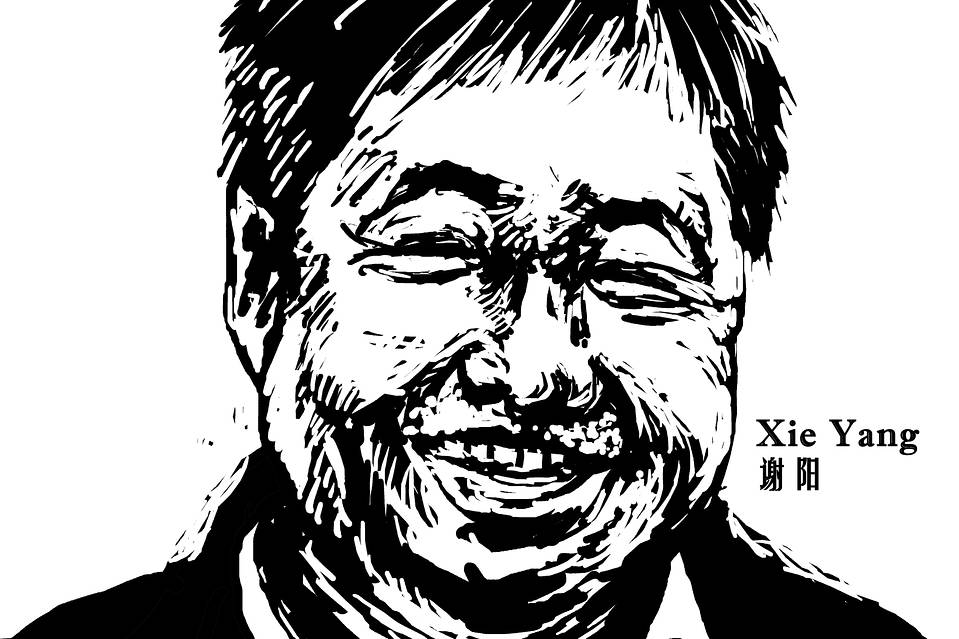

Developments in the crackdown on rights lawyers that began with the “Black Friday” or “709” sweep in July 2015 have continued into the New Year. Recent news on the topic has been dominated by reports that several of those detained have suffered physical and emotional torture. Xie Yang described his ordeal in a lengthy interview with his own legal representatives; Li Chunfu was released in a deeply traumatized state, unable to speak coherently; and his brother Li Heping and fellow rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang are said to have been subjected to abuses including intense electric shocks. A Washington Post editorial highlighted the first two cases on Friday, arguing that “in China, torture is real, and the rule of law is a sham”:

A nation under the rule of law must have a commitment that no one is exempt from justice. China has courts, judges and lawyers, but the Communist Party remains above the law. Two recent cases have dramatically illustrated how brutal and arbitrary punishment from the Chinese party-state can be, including its use of torture to silence dissent and break dissenters.

Imprisonment, forced confessions and deprivation are hardly new in China, but the fresh examples are raw and disturbing. The victims were lawyers committed to peaceful advocacy of human rights and dignity.

[…] The United States has regularly spoken out about the universal values of human rights and rule of law. President Trump has shown no interest in either and has endorsed the use of torture in interrogations. That can only embolden China’s leaders the next time they decide to apply thumbscrews to the champions of democracy and rule of law. [Source]

While some fear that Trump’s election “represents the biggest possible blow to everything that has been achieved in the realm of international human rights since the late 1940s,” others hope that his apparent willingness to confront China on an issue as sensitive as Taiwan’s status offers hope for a stronger line on rights issues. Prominent Chinese activists including Hu Jia, Chen Guangcheng, and Teng Biao established the China Human Rights Accountability Center earlier this month. The group aims to promote the use of recent U.S. legislation to sanction foreign officials involved in such abuses.

Others are turning elsewhere: the wife of more recently detained lawyer Jiang Tianyong, having appealed to the U.S. government in the past, wrote to German chancellor Angela Merkel last week in the hope “that she will pay attention to [his] situation and ask, ‘Where is he locked up?’ Can German diplomats meet him and tell us if he’s dead or alive? If he has been tortured? Has he been given his blood pressure medication? Have they been giving him other drugs, strange things?” On Wednesday, E.U. ambassador to Beijing Hans Dietmar Schweisgut expressed concern at the reported mistreatment of Xie Yang, and promised to “continue to take up this and other cases” with Chinese authorities. On Saturday, an E.U. spokesperson issued a further statement on Xie’s case and others:

The European Union expects that the competent authorities in China will investigate, without delay, the account of torture in the case of Xie Yang and the allegations of torture in the cases of Li Heping and Wang Quanzhang. Pursuant to Article 18 of China’s Criminal Procedure Law, if the accounts of mistreatment or torture are confirmed, this should result in the punishment of the responsible persons. In the meantime, all necessary measures to ensure the safety and wellbeing of these individuals need to be taken.

The release of human rights lawyers Xie Yanyi and Li Chunfu is a positive step. We reiterate our call for the release of the lawyers and human rights defenders who remain in detention, including Jiang Tianyong. [Source]

Within China, early January saw the formation of a “709 Trial Observation Group” “to bear witness to the illegal methods of the ‘709 model’ of persecution as well as the bravery of the 709 heroes […] from inside and outside the courtroom, in China and outside China.” Last week, dozens of mainland lawyers pledged to help Xie Yang sue his alleged abusers. Far from being cowed into inaction, some rights lawyers are even expanding their activities, with one group mounting a “mostly symbolic” legal challenge to authorities’ “severe dereliction of duty” in battling air pollution.

Another international protest at the 709 detainees’ treatment came on Monday, when a group of 20 lawyers and jurists published an open letter in The Guardian to mark the “International Day of the Endangered Lawyer” on January 24. Echoing another letter sent last year, they described denial of access to lawyers, pressure on families, “release” into effectively extended detention, defamatory media reports and apparently forced confessions, and alleged torture and other abuses including inappropriate medication.

We, the undersigned lawyers, judges and jurists, now write again to express our continued grave concern over subsequent developments in China, in particular the treatment of the lawyers and legal assistants named in our 18 January 2016 letter, as well as some of their close colleagues, supporters and family members.

[…] Xi Jinping has repeatedly stated that “China is a country ruled by law” and that “every individual [Communist] party organisation and party member must abide by the country’s constitution and laws and must not take the party’s leadership as a privilege to violate them”. Yet the events just described appear to move farther and farther away from those commitments.

China has signed and ratified the UN convention against torture and signed the international covenant on civil and political rights. By detaining and disappearing these lawyers and law firm staff, China is in breach of its international obligations as well as Chinese domestic criminal law and constitutional principles. It is also violating the UN basic principles on the role of lawyers, the UN declaration on human rights defenders and the UN body of principles for the protection of all persons under any form of detention or imprisonment.

In order to vindicate its claim to be a responsible stakeholder in the international community and to be a respected global superpower, it is imperative that China honour its international commitments to international conventions and human rights. […] [Source]

Read more on the letter from the American Bar Foundation.

Amnesty International’s Nicholas Bequelin also marked the International Day of the Endangered Lawyer with an op-ed at South China Morning Post:

Xi took office with the bold promise to “put power in a cage”, or deter official abuse of power, and followed through by giving fallen political rival Bo Xilai (薄熙來) the closest thing to a transparent trial by China’s standards, abolishing the notorious system of re-education through labour, and picking “the rule of law” as the theme of the fourth party plenum in 2014.

China has since put in motion an ambitious plan to address admitted deficiencies in its judicial system: corruption, abuse of power, political interference, miscarriage of justice, forced confessions and torture.

But at least two things are threatening this agenda. The first is the failure to recognise that rights granted on paper are effective only if redress is available when they are denied or violated. Without effective remedies, rights on paper are worthless, and lawyers are indispensable to securing these remedies.

Lawyers are not always popular figures, and China is no different. Chinese lawyers are accused of being useless and a waste of money, and even rabble-rousers. But the role of the legal profession remains crucial in the administration of justice, if simply because lawyers are the only ones within the justice system whose main duty goes to the plaintiff or the defendant. This is all the more important in a system that does not recognise judicial independence: without lawyers, ordinary citizens have virtually no hope of claiming their rights against powerful state machinery. [Source]

The account of Xie Yang’s torture comes from interviews conducted during meetings with his lawyers Chen Jiangang and Liu Zhengqing. Xie was charged last month with inciting subversion of state power and disrupting court order, and accused of having “long been influenced by the infiltration of anti-China forces and gradually formed his idea of overthrowing the current political system.” Xie’s interrogators sought to extract a confession from the lawyer, as well as statements implicating his fellow lawyers and supposed co-conspirators. One focus of questioning was a “Human Rights Lawyers Group” on Wechat, which the authorities appear to have regarded as a formal political organization rather than a casual chat group. They subjected Xie to deprivation of sleep and water, relentless interrogation, beatings, stress positions, and threats of harassment, violence or death against Xie, his friends and family, including his children. From a four-part translation posted at China Change:

It was around 6 a.m. when we arrived at the station, at the crack of dawn. Someone took me to a room in the investigations unit and had me sit in an interrogation chair—the so-called “iron chair.” Once I sat down, they locked me into the shackles on the chair. From that point, I was shackled in whether or not they were questioning me.

[…] The police had an auxiliary officer stay with me. He didn’t let me sleep at night and kept me shackled like that up until daybreak. For the whole night, the auxiliary officer kept a close eye on me and didn’t let me sleep. As soon as I closed my eyes or nodded off, they would push me, slap me, or reprimand me. I was forced to keep my eyes open until dawn. [Source]

Xie was subsequently transferred to another location for “residential surveillance”:

Yin Zhuo gave me three choices for how I should explain my actions as a rights lawyer: “Either you did it for fame, for profit, or to oppose the Party and socialism.” Looking at the case file now, many of the things I wrote or the interview transcripts they kept were not included. They said those documents were no good because they didn’t fit with those three explanations. In one interview I said that I handled cases in a legal way, but they thought that this didn’t fit with the three options they’d given me and forced me to write something myself.

[…] Since they’d set out three options, I could only smear myself. I did it for fame and profit, to oppose the Communist Party and the current political system—those words are in there. I had no right to choose whether to write them or not or sign my name to them. All I could do was write, sign. Whatever was written or whatever is in the transcripts, I had no choice. I could only choose from the three options they gave me—fame, profit, or opposing the Party and socialism. [Source]

They have a kind of slow torture called the “dangling chair.” It’s like I said before—they made me sit on a bunch of plastic stools stacked on top each other, 24 hours a day except for the two hours they let me sleep. They make you sit up there, with both feet unable to touch the ground. I told them that my right leg was injured from before, and that this kind of torture would leave me crippled. I told all of the police who came to interrogate me. They all said: “We know. Don’t worry, we have it under control.” Some also said: “Don’t give us conditions—you’ll do what we tell you to do!”

[…] They said I wasn’t being cooperative in the way I was writing statements. They wanted me to write according to what they wanted, even if it didn’t match the facts at all. They tried to force me, and I refused. There were other times when I was simply too tired and I couldn’t even pick up the pen. Mostly it was during the fourth shift, from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. When I couldn’t write, they would beat me. [Source]

They deliberately tortured me past the point I could bear it. I wanted to kill myself. To prevent me from doing so, they increased the number of “chaperones” (陪护人员) from two to three. The three of them surrounded me, watching me carefully lest I try to kill myself. After the first seven days, they interrogated me during the daytime and stopped at night. After about 20 days, they were afraid I’d kill myself and the number of chaperone shifts increased from three to four, with the number on each shift increasing from two to three. They watched me closely every minute, afraid that I would try to kill myself by ramming my head against the wall. In that state of wanting to die but not being able to do so, if I didn’t follow one of the three options they gave me and say in my statements that I acted for fame, for profit, or to oppose the Party and socialism, I would have been tortured to death. I had no other choice. [Source]

Speaking to The Guardian’s Tom Phillips, the American Bar Foundation’s Terry Halliday addressed the credibility of Xie’s account, saying that such treatment is “par for the course” in political cases:

“It all rings true,” he said. “Nothing would surprise me about the degree to which the authorities will go in order to get the kind of response they want.

“It seems to me that part of the evil genius of the Chinese security apparatus has been that they have perfected forms of enormous pressure on individuals that are so powerful that they can compel almost any individual to comply, but yet they are not so manifest with broken bones, or the shedding of blood or external marks that can be used by the media or advocates around the world to criticise the government for inhumane treatment,” Halliday added.

“It’s torture behind a veil. We are left in the position of having to believe or not the person describing what happened to them, with very little evidence externally that allows us to validate that.” [Source]

While Xie described the interrogation process itself, Li Chunfu’s sister-in-law Wang Qiaoling offered a series of accounts of its aftermath, which were also translated at China Change. She began with Li’s return home to his wife:

When she tried to pull him in by the hand, he was terrified and pulled away. Relatives who lived nearby heard that he’d been dropped off and rushed over, but rather than greet them Li became agitated and upset, jumping up and pushing them away, yelling “Get out of here! Danger!” Friends and family could do nothing but back away and sit at a distance from him.

Today (January 13), Li is still in a state of terror and confusion. When he saw his wife making a phone call, he shot his arm out and gripped her tight around the neck, growling: “Who are you calling?! You want to harm me!” As he yelled, he dug his fingers in, strangling her. Luckily, a relative was there and took control of the situation, pulling him away. [Source]

He recognized that I was his sister-in-law and tried to talk to me, but he trailed off before finishing the first sentence, hanging his head low as though in pain. He kept saying that he had a pain in his heart. His wife told us: “Last night he was saying that he felt like insects were biting his body inside, that his heart had been eaten away by bugs bit by bit, and there wasn’t much of it left!” The sadness we felt as we heard this while gazing on his lifeless face is difficult to put into words.

[…] This wasn’t the lawyer Li Chunfu of 18 months ago. That Li Chunfu dropped out of school at age 14, went south for work, got stabbed, slept in a cemetery, then managed to become a lawyer after six years of gruelling self-study. He had been taken into custody because of the human rights cases he had taken on — he had been locked in a steel cage, battered, and threatened, but that hadn’t changed him. I never imagined that 18 months of jail would torment him to the point of a mental breakdown, leaving him broken and paranoid. [Source]

Sitting outside the clinic, Chunfu’s eyes would fix on whoever he was looking at, and he had trouble communicating with people smoothly. At one point he blurted out to the lawyer friends with us: “By the first six months of residential surveillance I’d already gone mad. I was shouting and screaming.”

I felt a cold sweat when I heard those words come from Chunfu’s mouth all of a sudden. I didn’t question him further. I just fixed my gaze on him, not daring to think or speak. He continued: “On January 5 they took me out of the detention center. They didn’t go through any procedures. A lot of people are going to lose their jobs! They did everything to me. But I didn’t do anything illegal; all I did was, once, stand outside the public security bureau in the Northeast with a placard demanding my right to see my client. They wanted me to write a confession, but I wouldn’t do it no matter what. I knew that if I did it they would capture it on camera behind me, and my brother Li Heping and other lawyers would all be harmed!” He paused for a moment, then added: “Don’t tell anyone this. A lot of people will be hurt.” These are Chunfu’s exact words, and I’m not sure everyone understands what he means. [Source]

As we sat on the sofa and finished talking over medical treatment, Chunfu suddenly screamed: “Tell me! What are you still hiding from me!” I was struck dumb. I could only look upon Chunfu’s face, twisted up with a sinister expression, and his eyes, full of ominous glint.

Addendum by lawyer Chen Jiangang: Li Chunfu is in a state of paranoia, dread, and alarm. He’s always fearful. Fearful of something going wrong, fearful of people coming to take him away. When he sees an old friend he’s a little better, but even when it’s a friend talking to him, he’s still full of suspicion, foreboding, and dread. For example, when we went to eat a meal together, someone asked him to order. He responded: “What’s that mean? Is something going to happen?” When asked whether he wants to eat dumplings or noodles, he responded by repeatedly asking what that question was supposed to mean, and “why are you making me choose?”

*Translator’s note: Several human rights lawyers and activists reported that “Tell me! What are you still hiding from me?!” is what interrogators frequently yell during interrogations. [Source]

Human Rights Watch’s Maya Wang commented:

It’s no mystery what shattered him. Human Rights Watch has long documented the Chinese government’s use of torture, and human rights defenders are frequently treated harshly. Beatings, being hung up by the wrists, prolonged sleep deprivation, indefinite isolation, threats to one’s family – these are common techniques that can cause long-term physical and psychological harm.

It is less clear why Li Chunfu was targeted. Perhaps it was his 2014 demonstration outside a Heilongjiang police bureau, demanding access to his client. Perhaps it is guilt by association, since he is the brother of another prominent rights lawyer, Li Heping. Increasingly Beijing tries to tar activists as agents of hostile governments, and perhaps the authorities had painted Li Chunfu and fellow lawyers as such to justify more draconian treatment.

The Chinese government owes Li and his family answers – why Li was detained, what happened to him in custody, and who was responsible for his mistreatment. More than that, it has a legal obligation to pay for his medical care and rehabilitation and prosecute those responsible. Beijing will have zero credibility on the rule of law both at home and abroad so long as individuals are tortured with impunity. Li will likely never be the same after this horrific experience – and neither should Beijing. [Source]

There seems to be little prospect of transformative change, however. Some steps have been taken and others openly discussed to address the use of torture to extract confessions. Yet another post at China Change describes Li Heping’s long-running anti-torture activism, which it credits with prompting some of the limited reforms of recent years. But the U.N., Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty have all reported that abuses remain widespread, and are even integral to the way the legal system functions. New safeguards have been particularly ineffective in politically sensitive cases, in which the authorities can exploit loopholes in the name of national security. At her China Law and Policy blog, Elizabeth Lynch examined such “paper promises” in the case of Jiang Tianyong:

Not surprisingly, Jiang, who has yet to give up his advocacy, is back on the Chinese government’s radar, this time with much more serious charges that could land this civil rights attorney in prison for life. But there is one thing that should make this time different from Jiang’s prior detentions: the implementation of China’s new Criminal Procedure Law (“CPL”), amended in 2012. When these amendments passed, they were herald as more protective of criminal suspects’ rights, much needed in a system with a 99.9% conviction rate. In October 2016, the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”), Supreme People’s Procuratorate (“SPP”), and the Ministry of Public Security (“MPS”) doubled down on the 2012 amendments, issuing a joint opinion, reaffirming each agency’s commitment to a more fair criminal justice system.

But as Jiang’s case highlights, these are just paper promises. For Jiang, some of the provisions of the CPL are outright ignored. But more dangerously, the Chinese police have placed Jiang under “residential surveillance at a designated location,” a form of detention that was added to the CPL with the 2012 amendment. In the case of Jiang, this amendment is being used to keep him away from his lawyers and, with his precise whereabouts unknown to the outside world, in a situation where torture while in custody is highly likely. So much for better protecting criminal suspects’ rights.

[… S]tarting with the 2015 crackdown on lawyers and now continuing with Jiang Tianyong, the Chinese government has demonstrated that it will use the label of “endangering national security” to forgo the rights that it says it is committed to providing criminal suspects. In late 2015 and early 2016, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate issued two sets of rules ostensibly to curb the police’s abuse of residential surveillance in a designated location. But, as others have noted, the new rules seem to be designed more to ensure that everything looks good on paper than to guarantee criminal suspect’s rights and access to due process. The case of Jiang Tianyong appears to prove that even those new regulations have had no effect. [Source]

What hopes remain for effective reform suffered a further blow this month when Zhou Qiang, chief justice of the Supreme People’s Court, instructed workers in the legal system to “resolutely oppose the influence of Western ‘constitutional democracy,’ ‘separation of powers,’ ‘judicial independence’ and other harmful ideas. Make your stance clear, dare to use your force [….]” NYU legal scholar Jerome Cohen commented on his blog that “this statement is the most enormous ideological setback for decades of halting, uneven progress toward the creation of a professional, impartial judiciary. It has already provoked some of China’s most admirable legal scholars to speak out in defiance, and, despite their prominence, I fear not only for their academic freedom and careers but also for their personal safety.” The Washington Post’s Simon Denyer described the backlash:

Two open letters expressing outrage at Zhou’s remarks are circulating, one signed by 23 lawyers and another signed by 155 leading liberal intellectuals.

“In the past few years, the legal community has been working hard toward establishing an independent judicial system,” said Lin Liguo, a former lawyer based in Shanghai who wrote the lawyers’ letter.

Lin said Zhou’s remarks had burst reformers’ optimism. “What Zhou said is basically that we don’t need judicial independence at all,” he said. “That’s why people are so upset.”

[…] Eva Pils, an expert in transnational law at King’s College London, said Zhou’s speech came as a “real shock” to people in the legal system who had been educated to believe that China was striving for better rule of law and who found it unacceptable that their country was “departing so completely and so rapidly from the reform path.” [Source]

Zhou’s statement has not been the only discouraging sign, as Verna Yu explained at America Magazine:

In a separate address to law enforcement officials, Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed the primacy of “regime security.” Taken together the two statements indicate that the party is placing its own interests over the rule of law, and its ongoing crackdown on dissent may intensify, lawyers and human rights advocates say.

Just two days before Mr. Zhou’s speech, Mr. Xi told court officials and security officials that they must “heighten their sense of crisis and political alertness” to face all kinds of risks ahead of the 19th party congress, the most important political reshuffling event for the Communist Party that will take place later this year.

Analysts say these comments will embolden police and officials to step up an ongoing crackdown on government critics and amount to a reversal of China’s support of the notion of judicial independence in the past three decades. “The message from Zhou and Xi to police, prosecutors and courts is that they can brazenly crackdown on people who pose a threat to the regime,” said Beijing-based rights lawyer Yu Wensheng, who has handled many sensitive political cases and been tortured in police detention.

“To them, the security of their regime is the most fundamental issue. Rule of law is just a slogan for deceiving people,” he said. “For the sake of the regime and the establishment’s security, they are willing to do anything.” [Source]