China’s November 23 announcement of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) has stoked Sino-Japanese tensions and overshadowed U.S. vice president Joe Biden’s trip to Asia this month. But while Sheila Smith writes for the Council on Foreign Relations’ Asia Unbound blog that it may take some time to draw conclusions from the conversations Biden had in China, Japan and South Korea, The Washington Post’s Chico Harlan writes that Chinese and Japanese diplomats still “see little chance to talk it out:”

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Chinese President Xi Jinping, both in office for roughly a year, have spoken just once — for a matter of minutes. The Japanese and Chinese foreign ministers haven’t held formal talks in 14 months. There is zero contact between their coast guards and militaries.

“There used to be so many channels” of communication, said a senior Japanese Foreign Ministry official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive information. “But that has all but stopped.”

The decline in high-level contact, the most pronounced since Japan and China normalized relations 41 years ago, points to fundamental shifts in both countries that have made it harder for diplomats to control and solve problems. In particular, hardening nationalism in China and Japan has reduced the ability of officials to appear conciliatory. Japanese Foreign Ministry officers who appear to be sympathetic to China have been largely sidelined over the last 12 years, according to two former senior-level officials who handled Asian affairs. [Source]

The Sydney Morning Herald’s Andrew Hunter commented on Monday that the ADIZ reflects a predictably patient and long-term Chinese strategy to slowly accumulate a relative advantage over Japan on the issue of the East China Sea. For Foreign Affairs, David Welch claims that China’s announcement “clearly makes things worse, not better:”

The common wisdom, no less wise for being common, is that China declared an ADIZ in the belief that it would aid in its dispute with Japan over the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands. Chinese leaders could have believed this for one of two reasons: first, they believed that an ADIZ signals or confers sovereign rights; or, second, they believed that declaring an ADIZ covering the disputed islands would enhance their bargaining position. The former is demonstrably wrong; if this is what they believed, they should immediately fire their international lawyers. The latter belief would only be justified if bargaining was taking place and if Washington and Tokyo could be cowed. This has proved demonstrably wrong, too, and if this is what they had in mind, they should fire their political analysts.

It is evident that China miscalculated. But China is not the only country that is worse off as a result. East Asia has suddenly become a more dangerous place. [Source]

For The Diplomat, Zheng Wang concedes that the situation is dangerous but proposes that the parties declare a “zone of peace” in the air and waters around the Diaoyu Islands:

A zone of peace has been used as a tool for conflict management in many deep-rooted conflicts, from international to ethnic conflicts as well as between communities. As with any peace proposal, difficulties and challenges must be overcome. Given that the tension has already developed into something symbolic, it is highly probable that both governments would consider accepting such a proposal as a withdrawal from their current positions, leading to domestic opposition. With rising nationalism in China and Japan, the governments have little flexibility in their handling of the bilateral relationship. There are also particular obstacles for both sides. As the Japanese government believes that the islands are administered by Japan, this may lead them to consider the acceptance of this proposal as equivalent to relinquishing administrative power. In Beijing, the government may worry that the acceptance of a new zone of peace would in essence negate the ADIZ that they just announced.

To overcome this, Chinese and Japanese leaders first need to demonstrate their vision, courage, and determination to make peace. The establishment of the zone of peace is a crisis prevention tactic. It will not change any legal claims or the status of the territorial claims. If they want to avoid conflict, especially one arising from a small incident, they should take measures to decrease the likelihood of such accidents through using tools such as the zone of peace. Responses sparked by the risk to honor and face are not the work of rational actors. Next, the United States has to be brought in to play a critical role in the deal-making. The domestic difficulties in China and Japan make it unrealistic to expect either country to initiate the negotiation process with the other. Another party needs to take the first step to promote the zone proposal. Even though the United States is not a neutral third party, it can still adopt the role of facilitator. And this would be in the interests of the United States. [Source]

Meanwhile, former Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani writes in The New York Times that China may have “done the world a favor” by declaring its ADIZ – it was not the first country to unilaterally created such a zone, and its announcement may push global powers to the table to discuss who really owns the skies:

Do we really want to live in a world where each country follows the example of America and China and establishes unilateral claims to international airspace? This hardly seems wise at a time when global air traffic has doubled every 15 years since 1980 and is forecast to double again over the next 15 years.

Recognizing the threat that noncompliance might pose to civilian aircraft, the Federal Aviation Administration advised American commercial airlines to abide by China’s rules. This concession also helped China save face, but we are moving toward a more dangerous world if we permit every country the right to create air defense zones with distinct and different rules. A multiplicity of rules will lead to confusion for civilian airlines and pilots. Instead, we should create simple and clear multilateral rules binding for all countries.

U.S. officials accompanying Mr. Biden said that the status of the new zone is now “up to China.” But the world needs the United States to take the lead. The question is whether America will give up its own claim to unilateral action to do so. [Source]

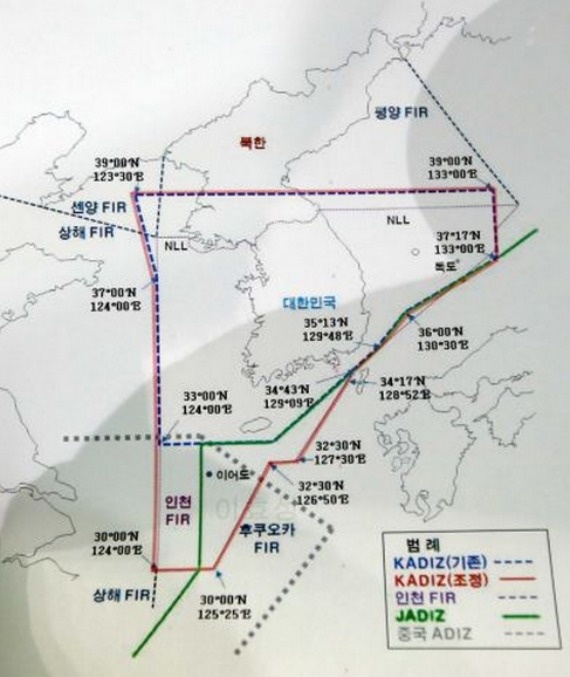

In addition to Japan and China, South Korea also claims the tiny islets in the East China Sea that lie within the ADIZ and have been the subject of numerous rounds of brinksmanship between the neighboring powers and other Asian countries. In a widely-expected move, South Korea announced that on December 15 it will expand its own air defense zone to incorporate a small rock that lies within China’s ADIZ. From The Wall Street Journal:

Seoul also raised objections because the new Chinese zone overlaps with South Korea’s air-defense zone and covers a submerged reef called Socotra Rock. South Korea and China have for years contested the rock, known as Ieodo in South Korea and Suyan in China, and economic rights to the ocean area around it.

South Korea built a nautical research station on the rock in 2003, giving it effective control. It lies southwest of the Korean peninsula, about 105 miles from the nearest South Korean land territory and 180 miles from the closest Chinese land.

In November, Seoul called on Beijing to redraw its air-defense zone to reflect its concerns. After the demand was rejected, South Korea said it would consider expanding its own zone. [Source]

The Wall Street Journal noted, however, that South Korea’s announcement was unlikely to infuriate tensions further – China reacted calmly as both the U.S. and Japan have accepted the plans.

See also previous CDT coverage of the East China Sea.