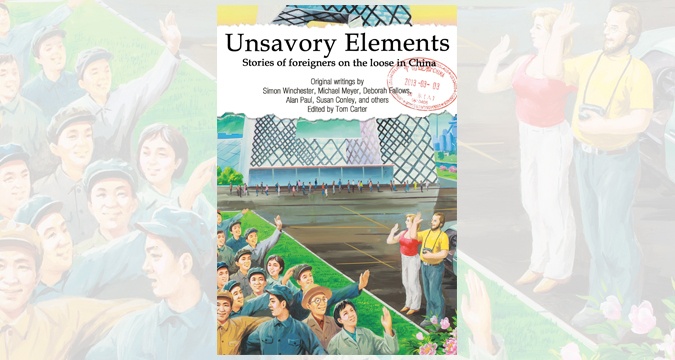

Originally from San Francisco, photographer and explorer Tom Carter spent two years backpacking 35,000 miles across all 33 Chinese provinces and has made his home in Asia and China for the past ten years. In the words of writer Anchee Min, his first book, CHINA: Portrait of a People, earned him a reputation as “an extraordinary photographer whose powerful work captures the heart and soul of the Chinese people.” Carter’s most recent book, an anthology called Unsavory Elements: Stories of Foreigners on the Loose in China, explores the expatriate experience through 28 independently authored essays.

I corresponded with Carter via email about thematic choices in Unsavory Elements, his controversial closing essay on prostitution in China, and his future plans:

China Digital Times: This collection of essays featuring expat life in China begins with the story of a man, Michael Levy, whose efforts at teaching Chinese high school students end up with the realization that he must falsify their college admissions essays. In “Paying Tuition,” a broke Matthew Polly finally learns how others play dirty after he is swindled multiple times at a kung fu academy. Peter Hessler experiences a moment of lost innocence when, in a dash of madness, he beats a thief in his hotel. In Deborah Fallow’s story “Bu Keyi,” she quickly begins to break the rules in public, telling lies and cutting lines to get ahead among other Chinese. What do we take away from this theme of foreigners who go to China only to become corrupted in a short time span?

Tom Carter: While it may appear to anyone perusing the pages of this book that these are simply chronicles of corruptible Caucasians in China, I’d hope that readers would glean a deeper cultural subtext, whereby we the writers are struggling to adapt in a pseudo-socialist society where laws are notoriously fluid; where invariably the only way to survive is to set aside our own Western black-and-white concepts of morality and ethics and learn to navigate the vague China Gray.

Bu keyi is the perfect example for this, China’s “phrase of choice for all things forbidden,” as linguist Deb Fallows writes, and then goes on to explain that the phrase in fact vacillates – as do all laws and rules in China – with circumstance. And if I can be a bit cheeky, not even the most corrupt Communist Party official in China knows when they are breaking the law here. Graham Earnshaw (publisher of Unsavory Elements), writing about illegally running an underground magazine in Shanghai by outsmarting the Propaganda Bureau, says it best: “Nothing is allowed but everything is possible. It’s just a matter of finding the right way to explain what you’re doing.”

CDT: The final essay which you narrate, “Unsavory Elements,” features a story of three men who visit a brothel where one man, Claude, becomes the “crass, complaining, and culturally insensitive” centerpiece. This story has generated significant media interest. Why do you think people responded especially to this particular story, and what do you make of the reactions?

TC: China has the highest per capita of prostitutes of any nation in the world – everyone’s doing it, but nobody is writing about it! Take any mass market memoir or travelogue about westerners in China that has ever been published, you won’t find any mention of prostitution, not because the authors are oblivious to its proliferation, but because they are confined by the narrow-minded editorial standards of Western Big Publishing. It’s disingenuous to readers and I refused to be party to the literary lies.

Of course I expected I’d be lynched by reviewers for portraying prostitutes in a humorously honest light instead of the tragic victims our media has for so long mythologized them as. Some say that it’s because I, a white male, am automatically disqualified from making light of their lives. Meanwhile, certain Chinese-American authoresses have best-selling books romanticizing the lives of 1930s Shanghai courtesans, completely glossing over that their circumstances were much, much worse than today. Write a clichéd period piece about prostitutes and you are praised by reviewers, but write a true tale about the working girls of modern China and they call for your deportation.

CDT: You noted that prostitution is illegal in China but that “the reality is that sex is for sale in just about every district in every large or small city across the People’s Republic” in large part because of the imbalanced gender ratio where many men cannot find a woman. In your story, children run around the brothel. You even check up on your friend in the act and chat with the prostitute while they are in bed together. Is the atmosphere around prostitution in China generally as casual as you depict in this story?

TC: It is and it isn’t. I think the crackdown in Dongguan that recently made international headlines best illustrates China’s love-hate relationship with prostitution. Dongguan’s GDP is co-dependent on all those wealthy businessmen and Communist officials conducting shady business deals together at KTV while pretty girls feed them seeds. And yet, the CCTV exposé that incited the sweep cowardly targeted the women who work at these venues instead of the corrupt Party members who patronize (and privately fund) them, thereby failing to eradicate the root of the issue. As such, it will be business as usual by next week, mark my words.

But it’s not just that prostitution is a necessary evil to which China’s government turns a blind eye to keep their single male masses at bay; there’s really nothing “evil” about it. These women are not being trafficked like certain NGOs with an agenda want us to believe; these are mercenary albeit marginalized businesswomen who said f*ck you to the evil factory bosses and are making a very comfortable living by exploiting China’s vast gender gap. As I ask in Unsavory Elements, “why stand on your feet all day for slave wages when you can get rich on your back?”

CDT: You were born and raised in San Francisco before moving to China on a whim with a longing for adventure. Do you go back to the U.S.? Have your feelings about America and your American identity changed since you left for your epic backpacking trip and since you made a life for yourself in China?

TC: I celebrate my ten years in China/Asia this month – this week in fact – and have only been home once. I miss San Francisco, but I don’t miss what America is becoming, and the irony is not lost on me that in the past decade the U.S.A. has devolved into a police state while China, an authoritarian regime, is now less so.

A television station in Tianjin recently produced a documentary about my time and travels in China, which was very flattering. Apparently it’s a rare thing for a foreigner to stick around China this long, and they genuinely appreciate that. So, you know, stay in America to have your phone tapped and your skull thumped for the smallest infraction by the pigs in blue, or come to China and have a television show made about you.

CDT: What’s next for you? Do you plan to work on any more writing projects or photography books similar to CHINA: Portrait of a People?

TC: I’m hoping to someday return to photography, which is my first love, and I have a few photo-book proposals with my agent, but the harsh reality of today’s photographic industry is that nobody is going to pay you to go take pictures anymore. In these times, most photography books need to be Kickstarted, a tactic that I have not yet warmed up to.

In the meantime, I have a couple more anthologies in mind that I would like to create, because I enjoyed working closely with writers and crafting their stories. But assembling authors for an anthology is extremely challenging for an independent editor like me who has no Big Publishing backing or budget. Unsavory Elements took two years to put together, so I fear it may be a while yet for the next one.