At China Media Project, Qian Gang traces the abandonment of Xi Jinping’s early rhetoric on constitutionalism—”ruling the nation in accord with the constitution”—following the omission of a major speech on the subject from a newly published collection.

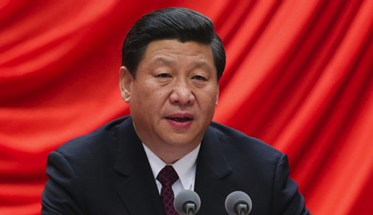

On December 4, 2012, Xi Jinping made a speech in Beijing to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the promulgation and implementation of China’s constitution. This speech attracted a great deal of attention both inside and outside China. In the speech, Xi Jinping said: “Rule of the nation by law means, first and foremost, ruling the nation in accord with the constitution; the crux in governing by laws is to govern in accord with the constitution” (People’s Daily, December 5, 2012). For Xi Jinping to use the words “first and foremost” and “crux” in these remarks represented a marked departure from the language of his predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

[“Ruling the nation in accord with the constitution” and “governing in accord with the constitution”] were Xi Jinping’s most jarring slogans after taking the Party’s top post in 2012, and they were closely tied to the subsequent championing of “constitutionalism” that we saw among intellectuals in China. The rise and fall of these terms reflects internal political sensitivities. In January 2013 — the month that the Southern Weekly incident erupted in Guangzhou around the censoring of the New Year’s message on constitutionalism — the terms did not appear in the People’s Daily. Then, after appearing once each in February and March that year, the terms disappeared from the paper altogether from April to July. In August, there was one appearance of either term, just as the propaganda tide against constitutionalism reached its height. In October 2013, there was one appearance. In November, two appearances. In February, 2014, there was one final appearance — and since then we’ve not seen the terms at all. [Source]

Qian concludes that the wording of statements from next month’s fourth Party plenum, at which rule of law is set to be the primary focus, will be “an important test of how and whether the agenda has shifted.” On Monday, Fordham Law School’s Carl Minzner wrote at East Asia Forum on the likely characteristics of a “new orthodoxy” on law that might emerge from the meeting.

First, it is extremely likely to import language from recent Communist Party propaganda efforts (that is, the ‘China Dream’) that emphasise China’s cultural distinctiveness. Similar lines have already appeared elsewhere. Several months ago, Xi Jinping commented to the Greek prime minister, Antonis Samaras, ‘your democracy is the democracy of Greece and ancient Rome, and that’s your tradition. We have our own traditions’. Naturally, this would help ideologically cage the efforts of Chinese liberals who seek to push for deeper reform based on Western legal models and international standards (as was the case with efforts in the late 1990s to bring China into compliance with WTO norms).

Second, it is probable that central authorities will confirm a heightened role for the Communist Party’s own extra-legal disciplinary system. This apparatus has already been bureaucratically strengthened as part of an intense anti-corruption campaign, in part as a tool to remove supporters of Xi’s rivals. Expect to see the definition of ‘ruling China according to law’ appropriately stretched.

Last, it will be worth watching to see how Chinese authorities attempt to reconcile recent judicial reform efforts with their increasing invocation of extra-legal mechanisms taken straight out of the 1950s and 1960s. […] [Source]

According to a Global Times report on the looming plenum, “analysts say [rule of law] holds the key to almost all challenges confronting China,” but “although China has been marching toward this goal over the past three decades, the pace slowed after the new millennium.” At China U.S. Focus last week, Tong Zhiwei of the East China University of Political Science and Law laid blame for this setback at the feet of fallen former security chief Zhou Yongkang, but many observers are skeptical that his removal will bring much improvement.

Read more on efforts to promote China’s adherence its own constitution, including Qian Gang’s earlier analysis of the movement’s fate, and on duelling conceptions of rule of law in China, via CDT.