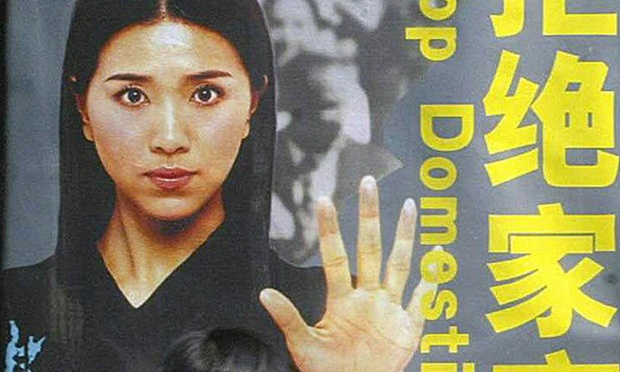

As China edges towards greater legal protections for sufferers of domestic abuse, a Sichuan court passed a suspended death sentence against one prominent victim on Friday. Li Yan killed her husband in 2010 after he reportedly burned her with cigarettes, locked her out on their balcony in winter, cut off part of her finger, and finally threatened her with an air rifle. She was sentenced to death the following year, but her case prompted a huge public outcry. On reviewing the case, the Supreme People’s Court ordered a retrial, which was held last November.

Reactions to the new sentence have been mixed: Li is now unlikely ever to be executed, but the law firm representing her described the verdict as the “second worst” possible. From Emma Graham-Harrison at The Guardian:

“It is not a precedent in the common law sense, but nonetheless it is a landmark case[,” said Amnesty International’s Nicholas Bequelin. “]It will serve as a foothold to future cases and also gives a measure of legitimacy to people who are pressing for more activism on the issue of domestic violence.”

[…] Li’s supporters say she had tried desperately to get help before she killed her husband. She had begged police and local women’s affairs officials for assistance, but even after one outburst of violence put her in hospital, they left her to fend for herself.

[…] “I think the court has given in to the pressure from the society which has yet to fully grasp the concept of domestic violence,” said Feng Yuan, feminist and longtime campaigner against domestic violence.

“I am very disappointed. Not that I had very high expectations before the retrial, but according to the latest guidelines on cases involving domestic violence issued by the supreme court, Li Yan’s case should not be counted as murder.” [Source]

In a separate statement, Amnesty warned that any encouragement the verdict offers is overshadowed by the recent five-week detention of and continuing pressure on five feminist activists.

Recent rhetoric on rule of law notwithstanding, the legal merits of Li’s case may have been overridden by outside pressure,Josh Chin reported at The Wall Street Journal.

Courts in China are often ordered to consider “social stability” in deciding on verdicts, giving them an incentive to decide in favor of those parties it sees as most likely to stir up trouble, legal scholars say. Ms. Guo and other supporters of Ms. Li’s said they suspected political concerns factored into both the original sentence and Friday’s decision.

In particular, they said, they thought the court was afraid of angering Ms. Li’s in-laws, who they described as being influential in local politics and who have clamored loudly for Ms. Li to be put to death.

Members of the Tan family cursed and attempted to attack Ms. Li’s lawyers inside the courtroom on Friday, according to the lawyer, Ms. Wan, and Xiao Meili, the women’s-rights activist. At one point, two of Mr. Tan’s relatives removed their shoes and threw them at the lawyers, missing each time.

[…] In the past, family members had threatened to commit suicide if the court gave Ms. Li a lenient sentence, said Ms. Guo, the lawyer. “For this to be the verdict, maintenance of social stability had to be a factor,” she said. [Source]

The prioritization of immediate social stability is also a common pattern in authorities’ handling of environmental protests, but has often proved short-sighted.

At The New York Times, Didi Kirsten Tatlow writes further on Li’s case and it’s context. During the retrial last year, she reported, a member of Tan’s family yelled that the female defense lawyers “should be raped 500 times.” Threats from Tan’s sister to court staff also appeared this week in an article by Tatlow on the court security doors which have “become a symbol of the antagonism between the people and the law.” Earlier this month, another female lawyer Cui Hui was allegedly beaten by court guards after trying to block one of these escape routes.

In a similar case this week, unidentified people in the central city of Hengyang beat several lawyers as they tried to cross a security barrier into a courthouse to pursue allegations of torture in police custody. Again, lawyers signed a petition protesting the assault.

“Security doors are very common in courts here. Judges don’t feel safe,” nor are they respected, Mr. Liang said. “Social conflict is running high, and it’s often expressed in courts. Any judge who makes an unpopular decision is believed to be corrupt. And litigants can be very unreasonable. They don’t understand the law and may react violently.”

So tricky has exercising the law become that judicial personnel are fleeing their jobs. The result is a shortage of qualified judges, according to Chinese news reports. [Source]