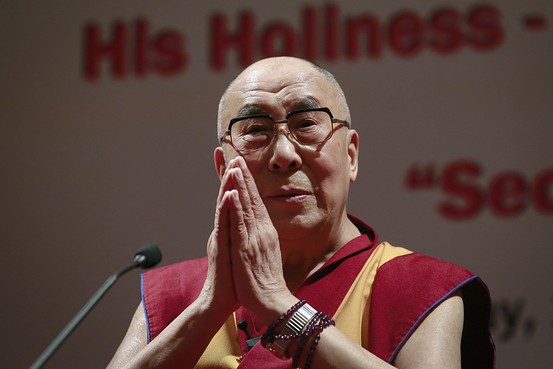

On Monday, July 6th, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, turned 80 years old. In a lengthy report filed from Dharamsala ahead of the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader’s birthday, the LA Times’ Barbara Demick outlined the complex political situation surrounding him and the homeland he fled after a failed 1959 uprising against CCP rule:

On the cusp of the Dalai Lama’s 80th birthday Monday, which he will mark during a three-day visit to Anaheim, China’s rising economic clout is slowly strangling the movement for Tibetan independence and, in the process, nudging the charismatic Tibetan spiritual leader off the world stage.

[…] The 94,000-strong Tibetan community in India, which for years has operated a government in exile headquartered in this mountain resort, is shrinking as a result of tighter Chinese controls on borders and passports that keep the 6 million Tibetans living in China from leaving.

At the same time, after a decades-long exodus, a new phenomenon is occurring: Tibetans are quietly requesting Chinese documents to go home, implicitly acknowledging that China’s rule over Tibet is here to stay.

“Everybody knows that the economic situation is better over there than here,” said a Tibetan engineer in his 30s who is preparing to return soon and asked not to be named for fear of reprisals. “We’re paid very well back in Tibet and people feel it is better to go back home than to live here in a shack.”

And yet Tibetans at home are not happy. Since 2009, 140 Tibetans have immolated themselves to protest Chinese policies that limit their freedom of movement, speech and religion, especially their right to venerate the Dalai Lama. […] [Source]

Demick’s report also includes details on economic, development, and security policies in Tibetan regions of China; foreign governments’ diminishing diplomatic engagement with the Dalai Lama as China’s economic clout continues to grow; Beijing’s recent dismissal of his suggestions that he may not reincarnate after his death; and the mixed reactions of exiled Tibetans about his “middle way” approach of seeking genuine cultural autonomy, not independence. (The Dalai Lama officially adopted this stance in 1979 but Beijing has since continued to view him as a separatist.) For more on contentious state policy and continued reverence for the Dalai Lama in Tibetan regions of China, also see a recent feature from India Today by Ananth Krishnan.

As the Dalai Lama was preparing to celebrate his birthday in Anaheim with more than 18,000 attendees (and countless more supporters worldwide), an English-language news website operated by Xinhua linked the occasion to an exiled Tibetan’s poverty-inducing request for money to ensure his graduation from Drepung Monastery. The report highlights continuation in the exiled monastic community of the feudal theocracy that the CCP’s “peaceful liberation” of Tibet asserts to have overthrown and reiterates the CCP narrative of benevolent sovereignty over Tibet:

[…] Since Ondrangkyi’s income could hardly cover her son’s required graduation amount, she was forced to consider selling the family’s belongings. The move could once again plunge the family into poverty, but she was determined to take the risk, because her son promised to come back home after getting the diploma and reunite with her and other family members.

The family saw a ray of hope when the price of their house soared in last winter, reaching a value of 90,000 yuan. Ondrangkyi gave the order to put it on sale.

[…] After a private agreement was signed between the family and a local buyer, Ondrangkyi had no choice but to move back to the family’ s pasture home with Jamokyi, her elder daughter, who has been taking care of her.

[…] What Ondrangkyi did not know was that part of the sum the younger son demanded would also be used for the celebrations of the Dalai Lama’ s 80th birthday. Jamokyi said once her younger brother told her in phone if the family could commit some money to the birthday celebrations, they would receive high recognition.

[…] Such a plan was aborted and the family’ s struggle was put to an end after their home sale was not approved by the government. Regulation governing the affordable houses program forbids such transactions for the sake of protecting people’ s livelihood. [Source]

In April, Beijing released a white paper praising central policy in Tibet and accusing the Dalai Lama of separatism, which English-language state media covered in extreme depth.

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed to mark the Dalai Lama’s birthday, American actor Richard Gere and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi criticized Beijing for its efforts to banish his influence from Tibet, and foreign governments for failing to exert greater pressure:

Perhaps one of the most remarkable achievements of the leader known to his people as “Kundun,” meaning “presence,” is his profound and unbreakable connection with the people of Tibet. They sometimes offer a simple greeting to visitors: “Listen to him.” It is too dangerous to say his name, but they mean the Dalai Lama. Many young Tibetans use a phrase in Chinese on their social-media profiles that means “I learn to be strong in waiting for the great teacher to return from afar.”

[…] The nonviolent nature of the Tibetan struggle should serve as an inspiration for a world riven by conflict and shattering acts of violence. Inside Tibet today, a younger generation now leads the nonviolent struggle to protect Tibetan freedom, religion and culture. Schoolchildren link hands and march to government education offices to protest when textbooks use Chinese and not Tibetan language. Teenagers write poetry in their own language in literary journals, expressing pride in their Tibetan identity. Young monks study the precepts of their religion in monasteries rigidly controlled by Chinese government cadres, even though the monks know that if they fail to denounce the Dalai Lama, they could be dragged away in the middle of the night and imprisoned.

At a time when China has increasing diplomatic heft, other nations grant too much accommodation to a government that imprisons its artists, free thinkers, lawyers, poets and human-rights activists. Indulging such a government undermines the values and interests of all democracies. We need to develop a more honest and clearheaded relationship with the current Chinese leadership—one that encourages China to become a better and more responsible global citizen. [Source]

In an essay for the Huffington Post, High Peaks Pure Earth editor Dechen Pemba recalls expressions of sincere longing for the Dalai Lama from Tibetans that she’s encountered in China and through her work from abroad:

Upon hearing that I was a Tibetan from inji-lungba (literally, the land of English people), the first question would invariably be, have you ever seen or met His Holiness? From Lithang in Kham to Labrang in Amdo through to Lhasa in central Tibet, in all three traditional provinces of Tibet, it was the same question over and over.

[…] I almost felt bad to say that I had, on several occasions. […]

[…] Later when I became a student in Beijing in 2006, I taught English as a volunteer to Tibetan students and had been warned not to make the classes “political” in any way. Imagine how I broke into a sweat when in my first ever class, a young man from Amdo decided to use the self-introduction round as a chance to speak in English about the situation in his home village, describing in detail how Chinese settlers were coming in in large numbers and the lack of religious freedom. One of my other classes was on the topic of “holidays”. When I asked the class, where they’d like to travel to on holiday, one by one they all answered India. I should have seen that one coming really.

[…] The term Kundun in Tibetan literally means “presence” but the Dalai Lama’s absence from Tibet is an all too real pain that is impossible not to feel. Or in a strange way, it could be interpreted as an overall presence in noting the absence.

In contemporary Tibetan songs and writings, themes of missing someone, often a parent, are common, as well as longing for a distant far off place. These poetic expressions are often ambiguous to avoid censorship and political problems, many have been translated into English on my website High Peaks Pure Earth. […] [Source]

Also see High Peaks Pure Earth’s translation of a birthday poem to the Dalai Lama by Woeser, or an article from The New York Times recalling earlier coverage of the Dalai Lama—from the death of the 13th in 1933 to the arrival of the 14th to India in 1959.