Cartoonists Rebel Pepper and Badiucao address the ongoing uproar over toymaker Lego’s refusal to fulfil a special order for activist artist Ai Weiwei. The company says that it avoids “actively engaging in or endorsing the use of LEGO bricks in projects or contexts of a political agenda.” Ai, though, has called the decision “an act of censorship and discrimination,” and many see it as the latest example of Western corporate and governmental “kowtowing” to a rising China.

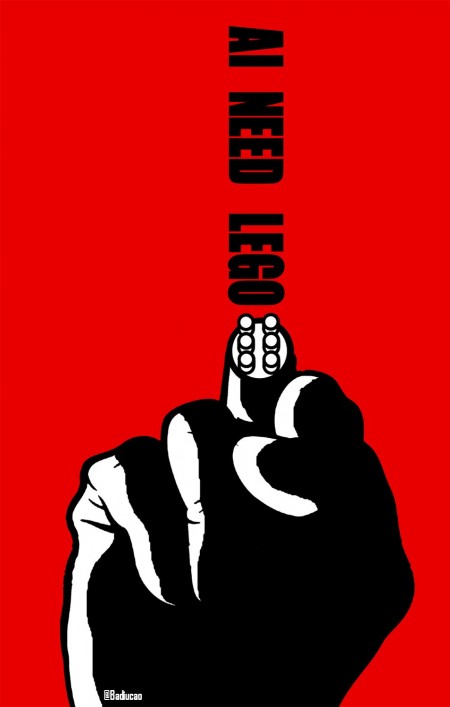

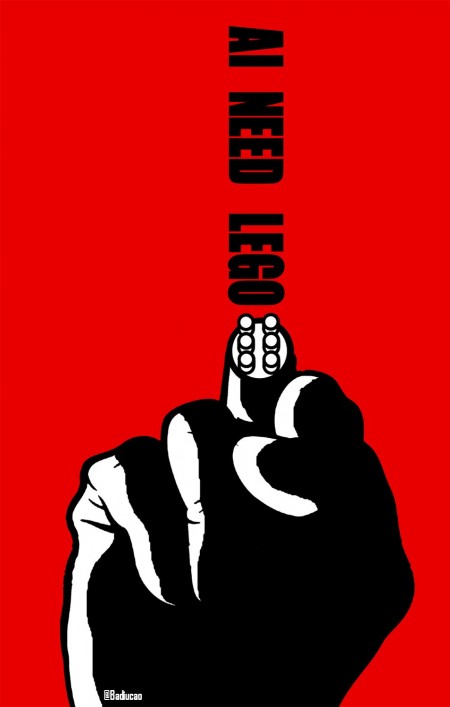

Supporters have now offered to step in to provide the required bricks. Badiucao portrays the donation drive as a push to restore Ai’s iconic middle finger:

On Instagram, Ai provided details of the donation program:

Ai Weiwei Studio is organizing a number of Collection Points in different cities.

Ai Weiwei would like to rent, borrow or buy second-hand a BMW 5S Series sedan, of which the color can vary, as a Lego container. The vehicle must have clear windows and a sunroof that can be fixed open with a 5 cm opening so that people can insert Legos. It should be free of any advertising or other decoration.

The car should be parked and locked in a central location of the city that can be easily accessed by the public. The vehicle should remain in the parking space for one month or a longer period of time, preferably in a location related to arts or culture, indoor or outdoor.

Ai Weiwei Studio will be solely responsible for the custody and removal of the Lego container.

Ai Weiwei will indicate the location of the containers on his Instagram and Twitter @aiww.

A mailing address will also be provided for donors.

[Source]

At The New York Times, Amy Qin described the previously planned exhibits and their evolution:

According to Mr. Ai, the rejected order was for several million Lego bricks that would have been used to create two works for an exhibition titled “Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei,” scheduled to open on Dec. 11 at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Mr. Ai said that for one of the works, he planned to use the Legos for a re-imagining of his 1995 photo triptych titled “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn.”

In the second, tentatively called “Lego Room,” the artist said he intended to create mosaic portraits of 20 Australian advocates for human rights, and information and Internet freedom. They include prominent rights lawyers like Michael Kirby and Geoffrey Robertson, as well as divisive figures like the WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange.

[…] Although the status of the two planned artworks is unclear, Mr. Ai said he was “excited” to see how things would evolve. He is now setting up Lego collection points after numerous offers of Lego donations on social media. [Source]

Ai has suggested that Lego’s decision was a concession meant to safeguard a recently announced Legoland park in Shanghai. Legolands are not operated by the Lego Group itself, though the company’s owners hold a substantial minority stake in the park operator. But the toymaker is also expanding production in China, which, despite issues with piracy, has become a major source of growth in recent years.

A report in the state-owned Global Times similarly presented the affair as a result of China’s growing stature. From Xie Wenting and Li Ruohan:

Feng Yue, a political science expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times that Lego’s reaction shows that Western countries, companies and individuals are beginning to see China as multi-dimensional as the country prospers and approaches the global arena with an open attitude.

Ai, a contemporary Chinese artist, is renowned for creating political artworks and openly criticizing the Chinese government.

[…] Some experts also believe that Lego’s refusal reflects Ai’s growing alienation from the West. [Source]

The company, however, maintains that the decision simply reflects its long-running policy to avoid political entanglement, and has nothing to do with China in particular. From comments received by email from press officer Roar Rude Trangbæk:

While we by principle cannot comment on the dialogue we have with our customers, partners, consumers or other stakeholders, I would like to clarify that we respect any individuals’ right to free creative expression, and we do not censor, prohibit or ban creative use of LEGO bricks.

We acknowledge, that LEGO bricks today are used globally by millions of fans, adults, children and artists as a creative medium to express their imagination and creativity in many different ways. Projects that are not endorsed or supported by the LEGO Group.

However, as a company dedicated to delivering great creative play experiences to children, we refrain – on a global level – from actively engaging in or endorsing the use of LEGO bricks in projects or contexts of a political agenda. This principle is not new.

In cases where we receive requests for donations or support for projects – such as the possibility of purchasing LEGO bricks in very large quantities, which is not possible through normal sales channels – where we are made aware that there is a political context, we therefore kindly decline support.

Any individual person can naturally purchase LEGO bricks through normal sales channels or get access to LEGO bricks in other ways to create their LEGO projects if they desire to do so, but as a company, we choose to refrain from actively engaging in these activities – through for example bulk purchase.

Citing client confidentiality, Trangbæk declined to provide earlier examples of this policy in action. Several episodes offer some support for the claim that it is a long-standing policy rather than a new concession to China, though a 2008 ad campaign featuring the fall of the Berlin Wall and Tiananmen’s Tank Man appears to show that this has not been entirely consistent.

[Updated at 22:19 PDT on Oct 26, 2015: According to Trangbæk, the Lego Making History campaign is “a very good example of creative use of LEGO bricks where we had nothing to do with the project. It was not sponsored nor endorsed by us.” Although reported to have been made in cooperation with a Lego PR manager, “the content as illustrated is not official approved LEGO content.”]

In March, Lego rejected a product proposal for figures of the four female justices on the U.S. Supreme Court. It later allowed its resubmission with three generic female justices.

In 2012, Lego sued the Czech Pirate Party over Lego-themed political advertising. One of the company’s demands was that the Party publicly state that Lego figures had been used without the company’s permission or support.

In 1996, Lego’s Polish branch did provide bricks for a concentration camp-themed art project, which then prominently claimed official endorsement. The Danish parent company took legal action against this, but dropped it in response to public outcry.

Ai told The Times that Lego had also provided bricks for use in “Trace,” a carpet of Lego portraits of political activists shown on Alcatraz last year. Chen Guangcheng, one of the work’s subjects, tweeted his support for Ai along with his own Traced image:

@aiww Upset to hear that @lego_Group has refused your request to purchase #lego for your artwork. pic.twitter.com/fOf2jcul7E

— 陈光诚 Guangcheng Chen (@iguangcheng) October 25, 2015

Ai added, though, that the company may have been unaware of the political nature of the exhibit. Trangbæk declined to comment on Lego’s involvement, or to say whether it had received any complaint about the exhibit from Chinese authorities or other quarters; he simply reiterated that “it is our general policy not to actively engage in or support projects with a political agenda – it is not new, nor is it limited to any specific region of the world or specific projects.”

At the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Chris Berg of the Institute of Public Affairs defended Lego against the charge of censorship, but suggested that its “peculiarly utopian ethic about the nature of play and creativity” does not readily translate into practical business strategy:

For instance, Lego avoids making realistic military kits or weapons because its founder, Ole Kirk Christiansen, didn’t want to make war seem like child’s play. Star Wars branded Lego has been central to the firm’s recent success. But as David C Robertson points out in Brick by Brick: How Lego Rewrote the Rules of Innovation and Conquered the Global Toy Industry, Lego nearly passed on the Star Wars license because “the very name … was anathema to the Lego concept”.

[…] Lego is not a company well-geared for political controversy. At first glance their policy on controversial uses of their product is sound and clear. No politics, no religion, no military. Chinese democracy activists won’t get Lego’s approval, but then nor will Klu Klux Klan members. Lego wants to remain above the grubby material concerns of politics.

Such anti-political neutrality is obviously impossible. Whether they like it or not, Lego is a player in the cultural life of the human species, and in a way that any of Mattel and Hasbro’s competing brands are not. Lego profits handsomely from that status. Perhaps a truer form of political neutrality would mean paying no attention to the ultimate use of bulk Lego sales. [Source]