As Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign nabs “tigers and flies”—corrupt officials at all levels of government—concern about the sweep’s true goals and efficacy are rumbling. Sometimes these doubts get louder, but they are quickly silenced. An open letter calling for Xi’s resignation, published on a state-sponsored website last month, described the anti-corruption campaign as “merely a power struggle.” Freelance journalist Jia Jia and the families of several activists living abroad were detained in connection with the letter, though none of them claim any role in it. Meanwhile, relations of eight current and former Politburo Standing Committee members are named in the leaked Panama Papers, including Li Xiaolin, the daughter of former premier Li Peng, and Xi’s brother-in-law, Deng Jiagui. That former security czar Zhou Yongkang could be given life in prison for amassing ill-gotten gains, while other elites remain free, feeds into the sense that the anti-corruption campaign is “a political purge to consolidate power,” as Chun Han Wong wrote in the Wall Street Journal. But the suppression of reportage and commentary on the Panama Papers hobbles its impact.

There is also doubt that the anti-corruption campaign can actually stamp out corruption by punishing those who simply followed the norm in a system that tacitly condones, even encourages, bribery and graft. “After decades of marketization, is it even possible to find a government official on the inside of the system with clean hands?” asked human rights activist Wang Debang in 2014.

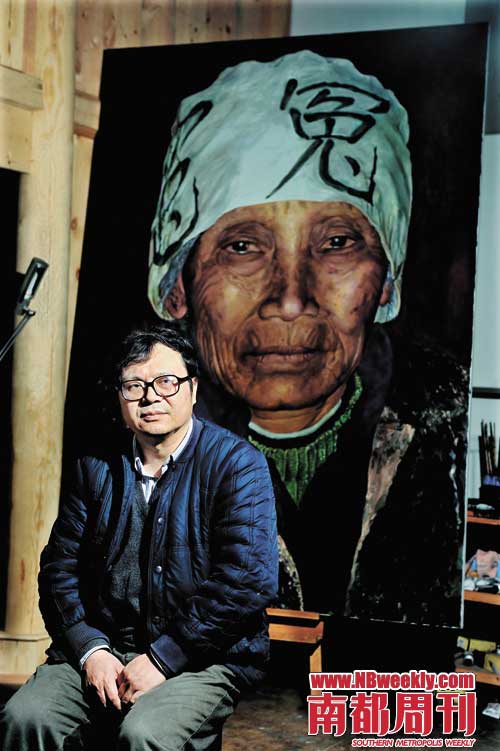

Rural sociologist Yu Jianrong shares this concern about the system that created corrupt officials. In the essay below, he talks about Li Jia, a Guangzhou official who is under investigation for “serious violation of discipline.” Yu remembers the thoughtful, though embattled, relationship he had with Li, and wonders whether the government attracts or molds the corrupt.

We Must Reflect on the System that Manufactures Corruption

Li Jia, the Guangdong Provincial Party Standing Committee and Zhuhai Municipal Party Secretary, has been sacked. When I heard this news, even though I had predicted it, I still felt a bit emotional, and even a bit distressed at yet another high official being reduced to an element of corruption.

Li Jia and I have crossed paths. It was a few years ago. At that time, he was still the Meizhou Municipal Party Committee Secretary. A Guangdong government unit was hosting an event at a famous scenic spot in Meizhou, and I had been invited to give a talk. Li Jia was in the audience. After the talk, Li Jia invited me to tea, on the basis of our sharing the same hometown. At tea, he told me he had a bachelor’s degree in engineering, a master’s degree in economics, and a PhD in philosophy from Sun Yat-sen University. He had gone from the university Communist Youth League committee to the provincial Youth League committee, and then to his position in Meizhou. He said that in places like Meizhou, where agriculture was the primary industry, one had to pay close attention to the three rural issues. He had therefore read practically every book and article I had written on the three rural issues.

This won me over. It is truly rare for government officials at his level to be able to accurately cite one of your opinions. I felt that I had encountered a kindred spirit. I poured out my concerns about pollution, land erosion, and hollowing out of the countryside, and the deterioration of grassroots organizations. He listened attentively, periodically nodding in agreement or directly challenging me, and expounded on his Green Meizhou project. We had a great conversation. He invited me with great sincerity to serve as a development consultant for Meizhou, and I happily agreed.

As a consultant, even though I received no compensation, I still felt that it was an important responsibility, and that I needed to fulfill this duty earnestly. Over the phone and by other means, Li Jia and I exchanged ideas about the establishment of grassroots governance, rural environmental protection, and ecological agriculture. He responded enthusiastically, but appropriately. That is to say, at that point we had fundamental respect for and trust in each other.

Later, something changed our relationship. Some farmers in Meizhou reached out to me to complain about a forced demolition project. I called Li Jia to tell him about it. He emphasized that there was a big project in the works. The farmers didn’t know what was needed for the interests of the whole. There was no choice but to carry out the forced demolition. Rapid economic development was the task that the Provincial Party Committee had handed him. He had to fulfill his obligations to the Provincial Party Committee leaders, who had given him such great authority. I maintained that the primary obligation of those in power is to guarantee that the nation’s laws are carried out, and that they should be responsible to the people. They should provide appropriate compensation for demolition and displacement. They should not allow farmers’ legal rights to be trampled for the sake of political achievement and commercial benefit. We got into a heated debate, and he hung up the phone. From that point onward, I never called him again, and paid much less attention to Meizhou’s development.

Not long after, Li Jia became the secretary in Zhuhai. During that time, relevant government units in Zhuhai invited me to teach a course to Zhuhai Municipal Party cadres, but I didn’t see him. But there was a time when one of his subordinates passed his greetings to me, along with his hope that I would be able to understand how much pressure he was under in his current role. I smiled and said nothing. I left Zhuhai right after I was finished teaching the course.

Now he’s being investigated. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection states that Li Jia and others were putting on airs while in public, only to violate Party discipline and abuse the law in private. They had maintained the appearance of propriety while indulging in an extravagant lifestyle. Or, as ordinary people would say, when the lights were on, they were people, and when the lights were off, they were ghosts.

I don’t know what crime Li Jia committed, but I trust that if the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection say it, there must be evidence. But I’m wondering, are the Li Jias of the world born this way? If they are, why is it that the Li Jias, who by nature hover between the human and the ghostly, are elevated to such important leadership positions? And if they’re not, what kind of force is compelling them to make such a change?

Based on my limited interactions with Li Jia, he has exceptionally high IQ and EQ. He received an excellent education at an elite school. If he hadn’t entered the government, it’s entirely possible that he would have become an engineer, a famous professor, or even a business tycoon. But he entered the government. Perhaps the Li Jias benefit from a political ideal born of their political position. But in the midst of actual political logic, they gain power, as determined by their superiors; and they are only responsible to their superiors, and are supervised only by their superiors. This authority outside the supervision of the public turns them into people that they themselves didn’t recognize. In this sense, Li Jia and others are the benefactors of this system, but are also the victims of this system. [Chinese]

Translation by Heidi.