Last week, Beijing prosecutors announced that no charges would be brought against five police officers involved in the death of Lei Yang, a Renmin University-educated worker at a state-affiliated environmental organization. Authorities acknowledged that the officers’ “inappropriate professional conduct” during Lei’s arrest for allegedly soliciting a prostitute had a “direct causal relationship” with his death, but cited Lei’s “fierce and persistent resistance” and “over-fed state” as mitigating factors.

The case has fueled middle class anxieties already agitated in areas from physical safety to education access and financial security. In a sign of its political sensitivity, a leaked media directive ordered “all websites, WeChat and Weibo accounts, and media apps [to] strictly control related comments.” (CDT has previously published two other directives related to Lei’s death.) Sina Weibo appeared to be automatically blocking all comments on posts including the phrase “Lei Yang case” (雷洋案), as well as searches for that term. At The Wall Street Journal, Chun Han Wong reports on reactions to last week’s news:

A number of prominent academics, lawyers and businessmen have publicly taken the prosecutors to task, saying the decision undermines the rule of law. A petition started by alumni from the university Mr. Lei attended has attracted more than a thousand signatures decrying the outcome as “inappropriate.” [See the petition’s text at CDT Chinese.] Some high-profile lawyers expressed willingness to represent Mr. Lei’s family in potential lawsuits against the five officers. [Lei’s family has since been awarded an undisclosed amount in compensation and decided not to sue the officers, citing “huge pressure” and exhaustion.]

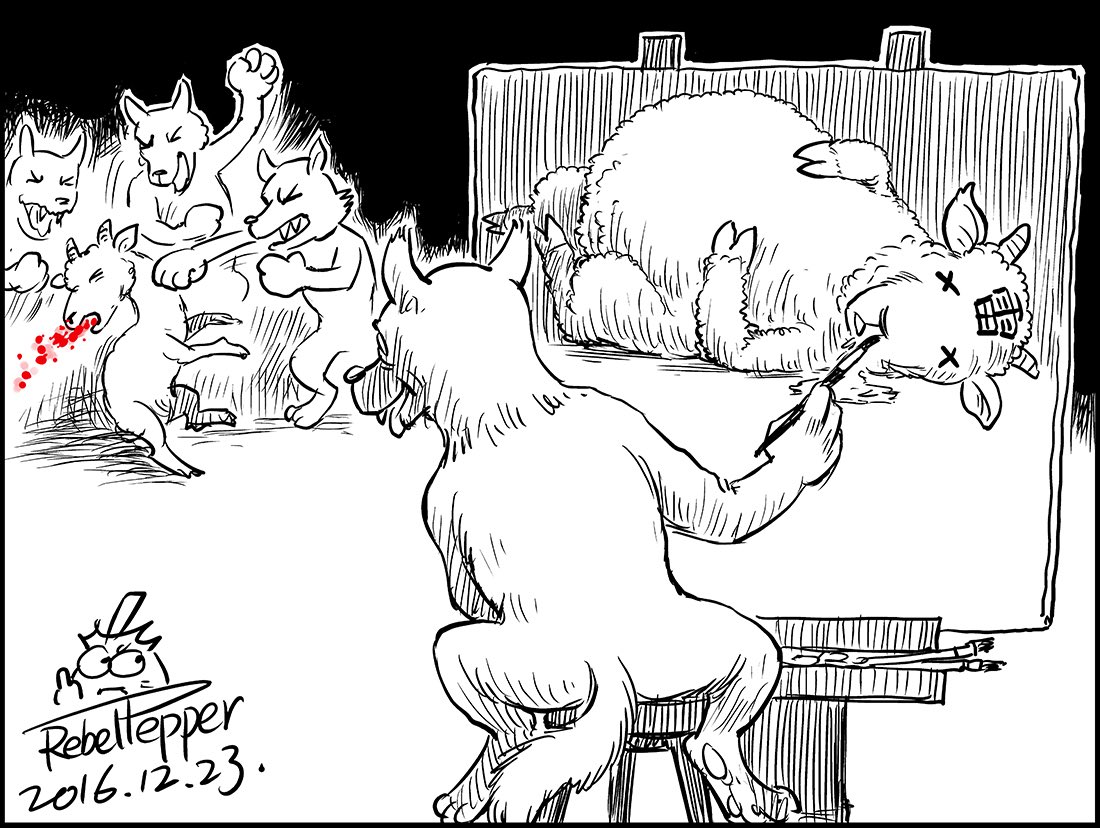

Though discussions of the decision were heavily censored on social media—and searches for Mr. Lei’s name blocked—two censorship-tracking websites, Weiboscope and Free Weibo, logged hundreds of deleted posts on the Weibo microblogging platform. [See some examples compiled by CDT Chinese.] According to WeiboScope, censorship on Weibo rose to a three-month high in the two days after the decision.

[…] The barrage of criticism amounts to a rare sustained burst of public anger by China’s burgeoning middle class. Though avid users of social media, white-collar professionals seldom respond collectively to government missteps or social problems. In recent years they have shied away from criticizing crackdowns on civil liberties’ lawyers and activists. [Source]

The Associated Press’ Gerry Shih looked further at middle class agitation over the case, and the disillusionment it has stirred with the country’s politicized justice system. In addition, he wrote, official moves to control commentary have only deepened some observers’ discontent:

Susan Finder, a Chinese law expert at Peking University’s School of Transnational Law, said Lei’s case sparked furor among China’s legal establishment, including corporate lawyers who normally pay relatively little attention to social justice cases.

What struck many of the establishment professionals, Finder added, was the sense that debate over a legitimate legal issue was being muzzled — a feeling many were not accustomed to. Several prominent legal professionals this week declined interviews.

“You wouldn’t think that the big firm lawyers would be so upset,” Finder said. “People feel like there’s no space for any other views.”

It was difficult to ascertain what online commentary was permitted. Censors took down an essay by a judge from Lanzhou city and even briefly blocked a legal analysis posted by a former Beijing government prosecutor surnamed Li, defending the city’s decision to drop charges.

Li, who refused to provide AP her full name though said she was now working in the private legal sector, said her post was unblocked after a day. In a follow-up post, she expressed incredulity at how she was censored in the first place.

“Did the relevant authorities hear the cries?” she wrote. “Freedom of speech is truly important.” [Source]

Online censorship was backed by offline warnings, according to Radio Free Asia:

Beijing-based rights activist Hou Xin said she was called in for questioning by police on Sunday after she posted a tweet supporting Lei, and was told to sign a guarantee of “good behavior” before being released.

“The police told me not to post anything else related to Lei Yang online. They told me I definitely shouldn’t do that, and they took my statement and made me sign it,” Hou said.

“They said they’d consult with higher-ups and then decide what to do with me; all I can do now is wait,” she said. “I signed the guarantee but I told them I couldn’t really make such promises because my civil rights were given to me by the constitution.”

[…] Rights lawyer Liang Xiaojun said he had received a police warning after giving interviews to foreign media on Lei Yang’s case.

“I have been told by the justice department that if I carry on doing that, they’ll deal with me,” Lilang said. “But I think these things need to be said, even if they do punish me.”

“I think that their demands [that I keep quiet] are unreasonable.” [Source]