On Monday, China Law Translate highlighted a public notice from county-level public security authorities in Henan regarding the death of a suspect while in custody:

On March 12, 2017,a suspect died while our bureau’s criminal investigation squad was handling the a case of a telecommunications fraud ring. Upon preliminary investigation by an inspection detachment from the Jiaozuo Municipal Public Security Bureau, the people’s police handling the case are suspected of using torture to extract confessions and collect evidence, and the Wen County procuratorate has opened a case for investigation. The public security organs will actively cooperate and resolutely punish case-handling personnel who have violated rules or laws. Any progress in the situation will be promptly released.

Henan, Wen County Public Security Bureau

2017/3/13 [Source]

The bureau’s ostensible openness represents a notable departure from similar cases in the past, such as that of Lei Yang, a young Beijinger who died soon after being beaten during his arrest for allegedly soliciting a prostitute. Because of Lei’s educational, professional, and family background—he graduated from a prestigious Beijing university, worked for a state-affiliated environmental organization, and had recently become a father—his case resonated widely among middle class Chinese. Authorities responded with a flurry of censorship measures: CDT published two leaked directives restricting coverage of Lei’s death. A third ordered “strict control” of online comments on the decision not to prosecute the officers involved, despite acknowledgement of the “direct causal relationship between Lei’s death and [their] inappropriate professional conduct.”

AFP’s Joanna Chiu reported on the Jiaozuo notice’s apparent break from this pattern:

“This is not the first time Chinese police admitted use of torture, but it is the first time the police released such information on a public network,” Chen Guangzhong of the China University of Political Science and Law told AFP.

“This seems to be a new communication tactic,” said Jeremy Daum of Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center in Beijing. [Daum is also the founder of China Law Translate.]

“If people believe that the situation is being reviewed openly in accordance with law and handled justly, they are more likely to wait and see what happens rather than take their concerns to the streets,” Daum told AFP.

Chinese courts have a conviction rate of 99.92 percent, and concerns over wrongful verdicts are fuelled by police reliance on forced confessions and the lack of effective defence in criminal trials. [Source]

A high-profile series of overturned convictions in recent years has seen several men exonerated after long prison terms or even execution. Last year, delegates at the legislative and advisory Two Sessions meetings in Beijing unsuccessfully proposed measures to prevent such errors in future. Some reforms have been adopted, but a U.N. panel, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International have all reported that pre-trial torture remains routine.

The state-run tabloid Global Times reported approvingly on the notice’s publication:

The police notice has been viewed by more than 13 million times, which shows the progress the government has made in terms of transparency, according to data provided by the administrator of a government affairs account on Sina Weibo, who goes by the alias “Zhengwuxinmeitixueyuan.

The account added that most people praised the police for admitting possible misconduct. “This is the first time that the police have stepped up and admitted some of their officers tortured those in custody…There is hope for a society ruled by law,” commented ” Lee miaomiao,” a Henan-based commentator, on Wednesday, in reposting the police notice.

“The notice is short but powerful … it shows the attitude of the police, the law enforcers. By doing so, the public is made aware of the facts,” wrote “Jimodexingzou,” an Anhui-based news reporter. [Source]

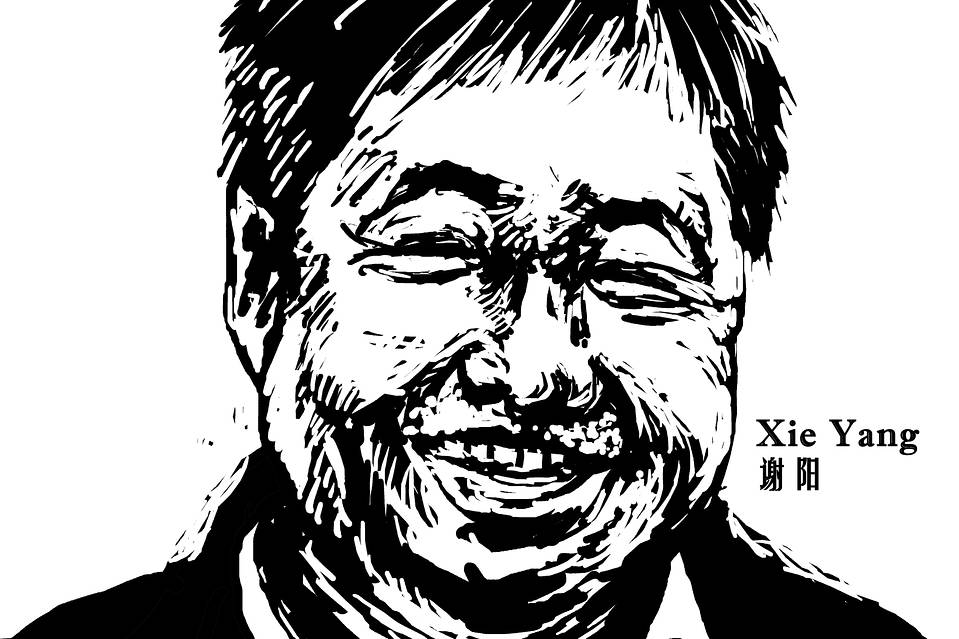

Besides the divergence from past cases like Lei Yang’s, the handling of the Jiaozuo case also contrasts with that of allegations of torture in the more politically sensitive cases of rights lawyers in the wake of the “Black Friday” or “709” crackdown in 2015. State media have denounced lawyer Xie Yang’s leaked account of his mistreatment as “cleverly orchestrated lies.” In turn, Xie’s own lawyer Chen Jiangang and others have rebutted the accusation. On Thursday, Nathan VanderKlippe reports at The Globe and Mail, Chen’s law firm was scheduled to be inspected by Beijing justice officials in what Chen and his supporters describe as retaliation for his continued advocacy.

“Why are they coming for me? It’s because of Xie Yang’s case,” Mr. Chen said in an interview.

“They want me to be silent.”

[…] But rather than remain cautiously quiet, Mr. Chen has grown more outspoken. On Wednesday, he posted to Twitter a photograph of himself holding a banner that says, “Oppose torture, support Xie Yang.”

He has also publicly sparred with state media over the accuracy of Mr. Xie’s story.

[…] The inspection of Mr. Chen’s workplace days later is China “tightening the screws and increasing pressure. It’s a way of threatening him and threatening the firm,” said Yaxue Cao, the founder of chinachange.org, which has translated and published the lawyer’s reports of torture. [Source]

The official backlash against Xie’s account may have been triggered in part by a private diplomatic letter from Australia, Canada, Japan, Switzerland, and seven E.U. member states, urging investigation of his claims. After news of the letter emerged this week, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs denounced it as a violation of judicial sovereignty and “the spirit of rule of law.” Notably absent from the list of signatories was the United States, an absence which agitated already deepening worries about the new Trump administration’s commitment to human rights advocacy. A Globe and Mail editorial on Tuesday argued that “the U.S. should show some courage and add its name.” At The Washington Post, though, Simon Denyer noted other possible explanations for the absence of signatures from the U.S., the E.U. as a whole, and the majority of its individual member states.

In fact, diplomatic sources said the decision not to sign the letter apparently was made within the State Department’s bureaucracy, rather than by Tillerson or any of his team. That may be a function of the chaotic nature of the transition since Trump took over — with several senior positions still unfilled — and the lack of a clear strategy on how to deal with China, rather than a sign of a fundamental shift in stance.

“I tend to think this is more to do with the fact that U.S. policy is so disorganized right now,” said Paul Haenle, who served in the National Security Council under George W. Bush and stayed on into the Obama administration. “Transitions are always really disorganized and confused, but this one is at a level I have never seen before.”

[…] Diplomats, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive matter, said Hungary had prevented the E.U. from signing as a bloc and threatened to do so in all such future cases. The Hungarian Embassy in Beijing declined to offer a comment.

[…] Yet it is also notable that 20 other E.U. nations besides Hungary also declined to sign the February letter on an individual basis. [Source]