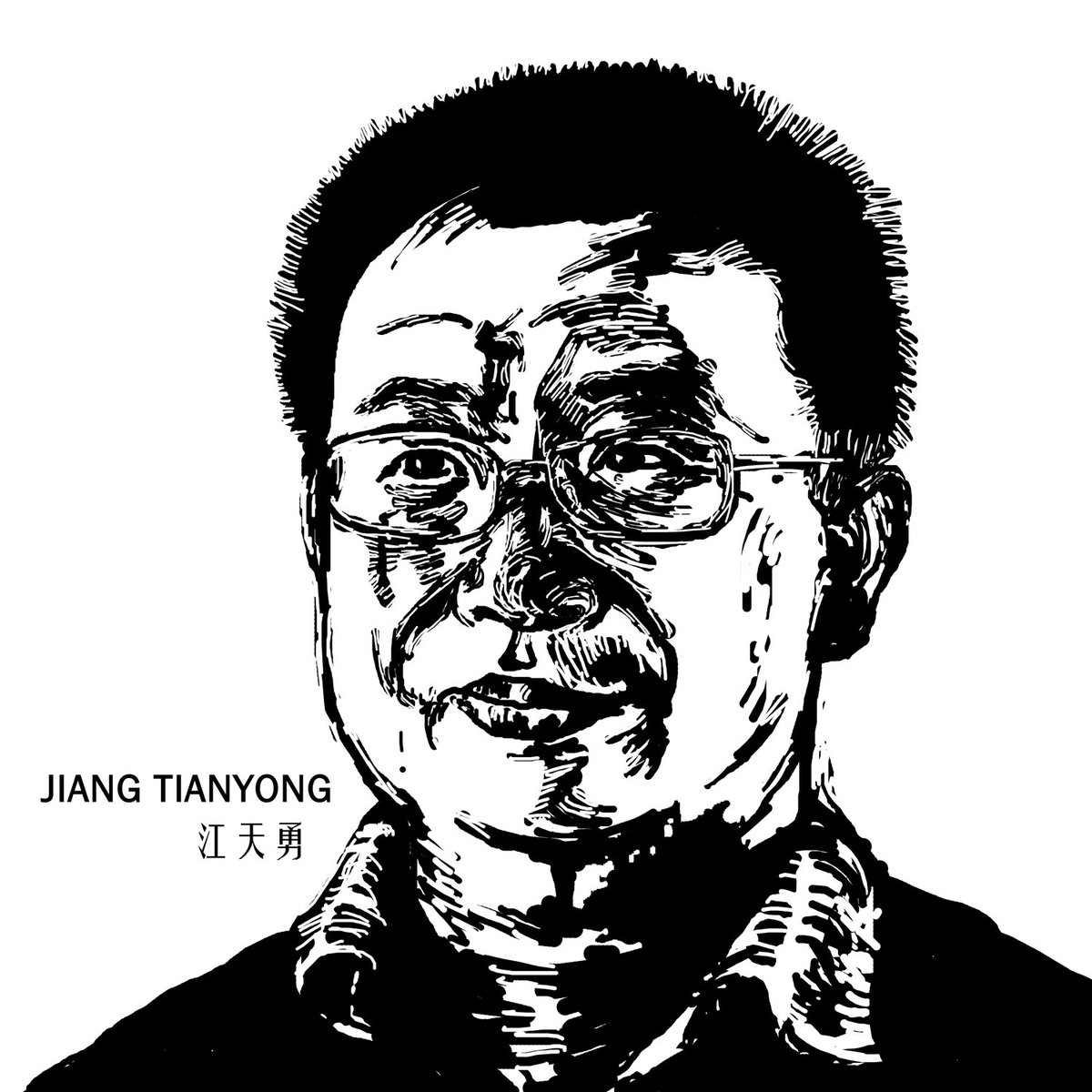

Jiang disappeared in November 2016 after traveling to central China’s Changsha city to provide advice and support to a fellow rights lawyer, Xie Yang. In December, authorities confirmed they were holding Jiang on suspicion of inciting subversion.

On Monday, six months later, the longest a suspect can be held without charge under Chinese law, his father received an official charge notice in the post, according to Jiang’s wife, Jin Bianling, who now lives in the United States.

The notice, dated May 31, said Jiang was being held on suspicion of subverting state power, a more serious crime, and was being held in Changsha City Number One Detention Centre, according to photos of the document seen by Reuters.

[…] "The crimes he (Jiang) is suspected of keep changing," Jin said. "It seems Jiang Tianyong has not admitted to any crimes, so they are going to keep torturing him until he confesses." [Source]

Jiang has spent the past six months under "residential surveillance," a form of secret detention that rights advocates warn places those held at risk of torture. Jin has claimed to have heard from a sympathetic official that Jiang has indeed suffered severe abuse, though local authorities have published video to rebut the accusation. Jiang also became involved while in custody in the torture allegations made by Xie Yang, ostensibly confessing to having helped fabricate them.

Jiang’s case, like many others since the 2015 Black Friday or 709 crackdown on rights lawyers, has been marked by the replacement of his original legal defenders, supposedly at his own request. The Associated Press’ Louise Watt reported on Friday:

Jiang’s wife Jin Bianling told The Associated Press that one of Jiang’s lawyers went to the Public Security Bureau in the central Hunan province city of Changsha on Wednesday to again request a meeting with his client. Jin said the lawyer was given a statement from Jiang declaring that he had dismissed his family-appointment lawyers.

"It must have been written by Jiang Tianyong under torture," Jin said by phone from California, where she moved in 2013 with the couple’s daughter to escape harassment from security agents.

[…] In March, one newspaper carried a purported interview with Jiang in which he said he concocted a story of a detained lawyer having been tortured by police. The interview was slammed by Jiang’s wife and rights groups as a sham, and his legal team questioned how reporters had been able to meet with Jiang when his relatives and lawyers have not.

Jin said Friday that her husband once told her and put in writing "that any statements, declarations or documents he signs under conditions of no freedom should be invalid because they do not reflect his real intentions." [Source]

Rights researcher Michael Caster recently noted a trend of similar pre-emptive disavowals by rights lawyers and other vulnerable figures as a defensive measure against forced confessions, statements, and changes of legal representation.

The NGO Chinese Human Rights Defenders described the practice of lawyer replacement in March 2016, detailing nearly a dozen cases:

[…] When families and family-authorized lawyers have demanded numerous times to meet the detainees to confirm any such “decisions,” police have rejected the requests. Police refusals to allow visits with the detainees to verify any changes of legal counsel raise the strong suspicion that the “decisions” have been coerced. All but one of the 11 cases that CHRD has documented are tied to the “709” crackdown targeting human rights lawyers.

[…] Though forced “dismissal” of defense lawyers is not unheard of in “politically sensitive” cases in China, it is alarming for there to be so many in such a short span of time, suggesting a systematic approach and decisions made in the high ranks of party leadership.

The suspected forced appointment of attorneys by police severely interferes with the independence of lawyers, and the detainees’ right to a fair trial will be seriously breached if they are tried while represented by attorneys forced upon them by authorities. Most of the individuals who have allegedly “fired” their lawyers have been arrested for “subversion,” a political crime for which a conviction carries a minimum of three years, and up to life imprisonment. Police appointed lawyers are unlikely to put forth a rigorous defense for a criminal suspect in a “politically sensitive” case, since such lawyers have been screened by authorities to ensure that they will stick to CCP-dictated guilty verdicts. For instance, police-appointed lawyers will not challenge “evidence” obtained through torture or coercion by police and get it thrown out in court, though such evidence, according to both Chinese law and international standards, is not legally admissible in court proceedings. [Source]

The China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group noted the practice in a comprehensive report on developments involving rights lawyers in 2016, published last week:

Most of the lawyers caught up in the 709 crackdown were pressured by the authorities to dismiss the defence lawyers that their families had chosen or ones that they had previously arranged to hire should they ever get into trouble. They were forced to accept lawyers appointed by the authorities, who proved to be unable to protect the defendants’ legal rights. During the investigation period, they often failed to submit evidence in favour of the defendants, they accepted evidence given by the prosecutors and gave up opportunities to question the defendants. In court trials, they raised no objection to the subversion charges.

Lawyers appointed by the families such as Li Baiguang (to represent Hu Shigen), Yang Jinzhu (for Zhou Shifeng), Ji Zhongjiu (for Gou Hongguo), Ge Wenxiu and Hu Linzheng (for Zhai Yanmin) were barred by the authorities from representing their clients. These lawyers, not recognized by the authorities, were in the dark about the dates of the trials until the day before or on the day of the trials when the court publicly announced the trials. According to Chinese law, courts should announce trial dates at least three days in advance. [Source]

The Asia-Pacific law association LAWASIA criticized this and other practices in a statement of continuing concern about treatment of lawyers in China late last month:

LAWASIA is compelled to express its deep concern regarding the reported treatment of lawyers in the People’s Republic of China (China).

LAWASIA previously stated its concern in July 2015, when it was widely reported that a large number of lawyers involved in ‘human rights’ cases had been arrested, detained or otherwise harassed by the authority of the Chinese government. As we approach the second anniversary of these incidents, it appears there has been no progress in the treatment of lawyers working on human rights or other public interest cases in China. The United Nations Committee Against Torture has indicated that some of those arrested during the incidents of July 2015 have since been subjected to torture or other forms of cruel or inhuman treatment during their detention. Further reports, available in the public domain, suggest that those prosecuted have been denied the right to access or retain defence counsel of their choice, as well as the right to a fair and public hearing by an impartial tribunal. Such treatment by the law enforcement authorities and judiciary of China would be in violation of the core human rights treaties and universal human rights instruments of the United Nations, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) (ICCPR) to which China is signatory. The Hong Kong Bar Association, a LAWASIA member organisation, rightly states that relevant obligations under international law are supported by provisions of the domestic law of China.

Given the information above, LAWASIA calls upon the government of China to:

i. observe its obligations under international human rights law;

ii. ensure that those prosecuted are afforded their proper rights to:a. access the assistance of a lawyer of their choice, and

b. a fair and public hearing by an impartial tribunal; andiii. ensure that lawyers in China are ‘able to perform all of their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference. [Source]

Besides pre-emptive disavowal, another approach to the replacement of preferred lawyers and other procedural issues came last week from Lee Ching-yu, wife of Taiwanese democracy activist Lee Ming-che, who was also arrested for subversion last week. His case has prompted protests from both current president Tsai Ing-wen and her Nationalist predecessor, Ma Ying-jeou. Following a series of tweets marking the Tiananmen crackdown anniversary on Sunday, she added:

I also want to use this opportunity to call on China to deal with #LeeMingChe case in a civilized manner & to let him come home

— 蔡英文 Tsai Ing-wen (@iingwen) June 4, 2017

But as Taiwan’s official Central News Agency reported last week, Lee Ching-yu appears to have little hope of such "civilized" handling, and has decided not to endorse the process by appointing a lawyer to defend her husband:

The wife of Lee Ming-che (李明哲), a Taiwanese human rights advocate who has been detained in China since March 19, on Thursday said she is not hiring a Chinese lawyer because China is ruled by men, not by law, and what she needs is the aid of legal consultants in Taiwan or other civilized countries.

This is the first time that Lee Ching-yu (李凈瑜) has made comments on why she has not hired a Chinese lawyer after her husband was arrested more than 70 days ago in China.

A Taiwan Affairs Office spokesman in Beijing said on May 26 that Lee Ming-che had been arrested on charges of "subverting state power" and had been in detention in Hunan Province since March 19.

Lee Ching-yu said she has no confidence in courts in China. If she hires a lawyer for her husband, that would mean she has recognized the Chinese courts are those in a "civilized" country and accepted the legitimacy of their rulings, which will undoubtedly put her husband in danger, she said.

A court in a state ruled by men is like a fascist theater, or a circus show, "so why should I spend big money to hire a lawyer to play a show with its director?" said Lee Ching-yu. [Source]

After unsuccessfully trying to travel to Beijing to seek information on her husband’s whereabouts, Lee Ching-yu testified on his case to a U.S. congressional committee last month alongside other members of the burgeoning advocacy movement among victims’ families.