In February, Yu Huan from Liaocheng in Shandong received a life sentence for stabbing several loan sharks—one fatally—who were harassing his mother. The case prompted a popular outcry, both over the harshness of the punishment and the alleged negligence of police officers who had previously left the scene without ensuring Yu and his mother’s safety. (Similar suspicions also arose in the sensitive case of a Sichuan schoolboy’s death in April. The officers in Yu’s case were later found not to have acted improperly.) On Friday, the provincial high court revealed the outcome of Yu’s appeal: no exoneration, but reduction to a five-year sentence. From Philip Wen at Reuters:

Yu, from Liaocheng in Shandong province, was sentenced to life in jail in February after he used a knife to attack four of his mother’s creditors who taunted and exposed themselves to his mother while demanding a 1 million yuan ($146,000) debt be repaid in April last year, according to state media. One of the creditors died.

In demanding repayment, one of the creditors exposed his “nether regions” and “gyrated” in front of Yu’s mother while flicking cigarette butts at her and forcing her to smell Yu’s shoes, the Shandong High Court said in its judgment.

Widely referred in media as the “Dishonored Mother case”, the initial sentence evoked widespread sympathy for Yu, whose defense of his mother resonated in a country where filial piety is considered a core value.

The court said that while Yu acted in part to protect his mother, a five-year sentence was appropriate given his actions went beyond reasonable self-defense, and that he later resisted arrest when police arrived. [Source]

The case has continued to attract widespread public attention with this latest development. The reduced verdict has triggered some concern about the influence of public opinion, and whether the legal merits of the case or the political imperative of dampening popular anger had won the day. From Javier C. Hernández And Iris Zhao at The New York Times:

Fu Hualing, a law professor at the University of Hong Kong, said the case had posed a predicament. On the one hand, officials may have been eager to show some sympathy for the harsh circumstances the defendant had faced. On the other, Professor Fu said, the government most likely wanted to signal that it would not tolerate violent acts.

“The state doesn’t want society to use violence on its own, regardless of how legitimate it might be,” Professor Fu said. “The state wants to monopolize the use of violence, to tell people, ‘Come to us, we will help you out, but don’t do it on your own.’ ”

[…] Public reaction to the ruling was mixed on Friday. While many people praised the lighter sentence, calling it reasonable, others said they were distressed that the court appeared to have been swayed by popular opinion.

“After you kill someone, all you need to do is spend a little money to hire some people to cause a stir online, then you’ll be commuted,” one person wrote on Weibo. “Too easy!” [Source]

Efforts to use public opinion as a lever in the courtroom have been blasted by the authorities: rights lawyers held in the 2015 Black Friday or 709 crackdown were accused of operating a “criminal gang” to employ such tactics. At the same time, official bodies have not hesitated to try to sway public opinion against defendants such as the detained lawyers, airing confessions widely suspected to have been extracted by torture or coercion, and sharing accusations that they were part of foreign plots against China. The contrast reflects official views on the purpose of China’s legal system: read more on rule of law and the crackdown on lawyers from The Economist, via CDT.

The goal, an editorial at Global Times argued, should be “constructive interaction between law and public opinion”:

In recent years, a significant portion of heated debates on the Internet have involved judicial issues and most debates target a specific case. This is certainly a brand new phenomenon in the process of China’s building of the rule of law. How can courts handle a case according to the law without being interfered with by public opinion? To what extent should judicial proceedings be subject to the supervision of public opinion? What is the boundary between the two issues? Chinese society has gradually developed an understanding as cases which spiral into high-profile events igniting public debate have emerged one after each other.

Court decisions are generally not against the opinion of the majority of the public. However, once such a discrepancy occurs, we need to narrow it. The discrepancy may result from two circumstances. There can be problems with the rulings issued by grass-roots judges and their verdicts sometimes need to be overturned. The public may be misguided given the insufficient information available to them or they may not have an adequate understanding of the law and relevant regulations. In the latter case, it is necessary to make adequate and correct information available to the public.

[…] In an era which embraces diversified opinions, public opinions may not all be mainstream but they are all part of the forces which drive society forward. Constructive interaction between law and public opinion can play an indispensable role in promoting the rule of law on all fronts in China. How can China achieve constructive interaction between law and public opinion? China is exploring possibilities and it has been said that its efforts have yielded noticeable results. [Source]

An English-language commentary posted to People’s Daily’s Facebook account (and shared on its similarly Great Firewalled Twitter feed) hailed the new verdict as having “taught the whole nation a class of rule of law”:

China has mobilized law enforcement authorities to popularize law, which is reflected in restoring the case in detail as much as possible, as well as in the strict, comprehensive and objective Judgment in accordance with the law. According to the court verdict of the second trial of Yu Huan, the certifications of fact were more detailed and the court had also responded to different opinions respectively. It was like a fair and objective report, which allowed the public easily and comprehensively regard Yu’s legal responsibilities. As the jury trial in the U.S. justice system, it protects the course of justice and plays a positive role in education of rule of law at the same time.

When the case touches the most sensitive nerves of society, no matter which country’s courts, must face the complex relationship between law and public opinion. It should be noted that the public opinion played a significant role during the whole process of Yu’s case. It not only allowed us to think about the benign interaction between public opinion and ruling of law, but also let more people realize that only maximum judicial openness can eliminate misunderstanding and dispel suspicion. [Source]

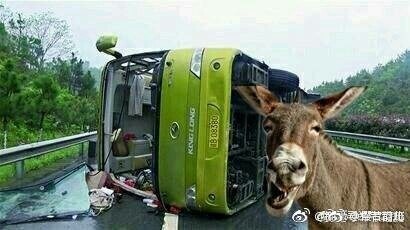

An earlier round of online debate over the role of public opinion in Yu’s case spawned the self-deprecating term “Donkey People,” a CDT Word of the Week in March.