Canadian journalist Nathan VanderKlippe, The Globe and Mail’s Beijing-based Asia correspondent, was detained in Elishku Township, Xinjiang on August 23 for over three hours. VanderKlippe in 2014 won an Amnesty International media award for his reporting on Uyghur repression and violence in Xinjiang amid an ongoing terror crackdown in the region. His detention came as foreign journalists in China are experiencing increased harassment, and as state security policies in Xinjiang continue to tighten. At The Globe and Mail, Ann Hui reports:

Mr. VanderKlippe arrived Wednesday evening in a small village in the Elishku township in Xinjiang province. He had been attempting to interview locals for less than 15 minutes when a police officer pulled up next to him on a motorcycle. Two more police officers soon followed, along with others who appeared to be government officials. He identified himself as a journalist, and was told to follow the men back to a local government office.

“At one point, I asked, ‘Am I free to go?’ And one person said ‘of course.’ But the other said, ‘let me check,’” Mr. VanderKlippe said. “It was pretty clear I was not free to go.”

At the office, the men demanded to search through his belongings, including a bag and camera. He initially pushed back, but eventually relented. “They said the regular rules don’t apply to them.”

The officials then demanded to look through his computer. Again, Mr. VanderKlippe pushed back, and this time the officials backed down. He was taken to a nearby restaurant for a small meal instead. But upon return to the office, they again demanded to see his computer – this time taking it away from him.

[…] Globe and Mail editor-in-chief David Walmsley called the harassment of the journalist “deeply disturbing.” […] [Source]

After being released, VanderKlippe tweeted:

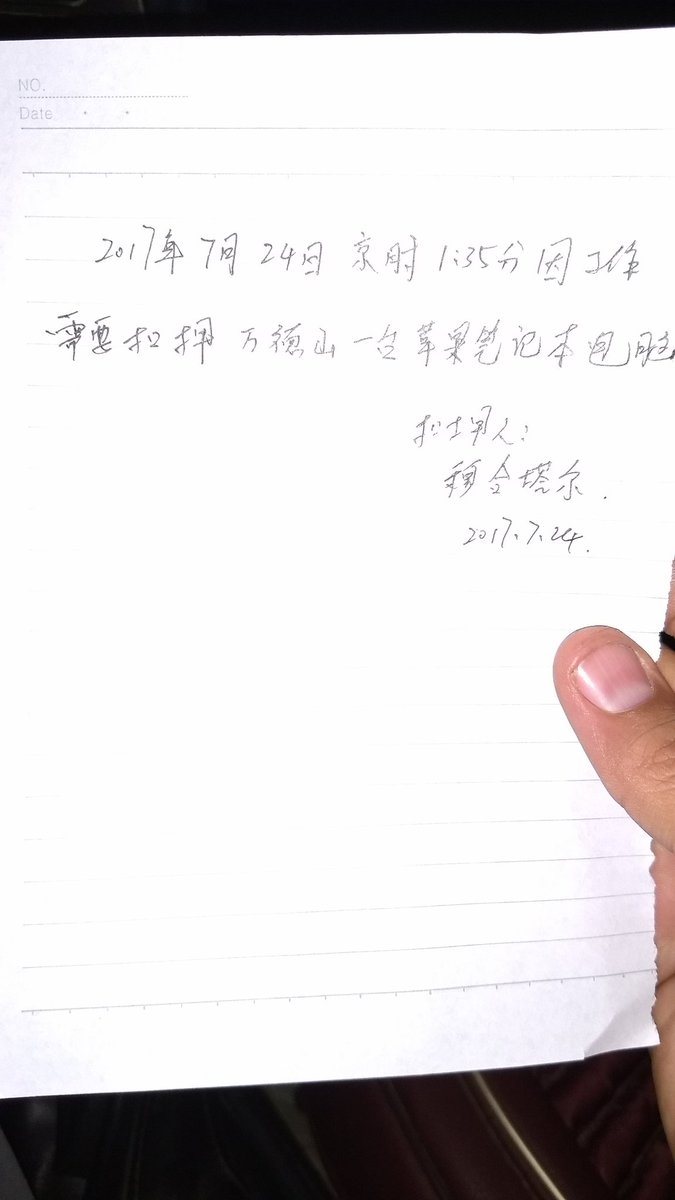

Was detained for more than three hours in Xinjiang tonight. Authorities have now seized my computer, wrote only a handwritten seizure note.

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 23, 2017

Just to be clear, I am no longer being detained. But I am being followed as I drive 200 kms back to a hotel that accepts foreigners.

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 23, 2017

My computer is now with the Chinese Ministry of State Security, who told me normal rules on seizures etc don't apply to them.

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 23, 2017

This is as formal as it gets when China's Ministry of State Security seizes a foreign journalist's computer. pic.twitter.com/dEJFVxzYgx

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 23, 2017

My secret police tail has left me. And their car, of all the strange things tonight, has a maple leaf on the back.

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 23, 2017

Mark McKinnon, VanderKlippe’s predecessor for The Globe and Mail in China, was similarly expelled from Xinjiang in 2009.

Xinjiang is the frontline of a controversial nationwide crackdown on terrorism that began in 2014. The campaign has been criticized by human rights advocates for targeting members of the Uyghur ethnic minority, which some observers see as further enflaming ethnic tensions. While China’s nationwide media controls have long been tighter in sensitive ethnic minority regions, since the ongoing campaign began authorities have enhanced their measures to control the media narrative on the region. Journalists are regularly barred from scenes of unrest and are closely monitored when there, giving official media outlets a near monopoly on coverage. Amid this tight control, information is often first reported by advocacy groups and foreign government-funded media organizations, whose reporters have also seen China-based family members harassed.

VanderKlippe has tweeted a few updates on the status of his seized laptop, and on the levels of security sensitivity in the region:

Official now tells me my laptop had to be seized because "there are a lot of fake journalists in Kashgar right now"

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 24, 2017

While brought to global attention recently by U.S. President Trump, the term “fake news” has long been employed by Chinese authorities to counter unfavorable coverage.

Apparently I was a mere lost luggage case. Kashgar official tells me my computer has been "found" and will be delivered to me.

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 24, 2017

Well this is good news. My computer was apparently seized for my "safety." And there apparently is no Ministry of State Security in Kashgar

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 24, 2017

Not a single bottled beverage in boarding areas at Kashgar airport. Apparently they can't get them past security. pic.twitter.com/sggAqEXZSU

— Nathan VanderKlippe (@nvanderklippe) August 24, 2017

Among his tweets, VanderKlippe recommended that those concerned about reporting conditions in China follow the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China (@fccchina)‘s regular updates. This week, FCC China tweeted two incident reports of foreign journalists and reporting assistants experiencing harassment while attempting to report:

Incident report from de Volkskrant correspondent Marije Vlaskamp on interference she faced reporting in northeastern China: pic.twitter.com/4IvctM667a

— Foreign Correspondents' Club of China (@fccchina) August 21, 2017

VOA journalists report being physically restrained, falsely accused, forced to delete footage while covering a trial in Tianjin. Details: pic.twitter.com/KNsLNbuwGh

— Foreign Correspondents' Club of China (@fccchina) August 23, 2017

In March, a BBC reporting team was attacked and forced to sign a confession during their efforts to cover a petitioner en route to Beijing ahead of this year’s top national political meetings. In April, an AFP reporter was detained in Changsha while trying to cover the scheduled (but postponed) subversion trial of a rights lawyer Xie Yang.

Read more about media conditions and control, foreign correspondents, and Xinjiang, via CDT.