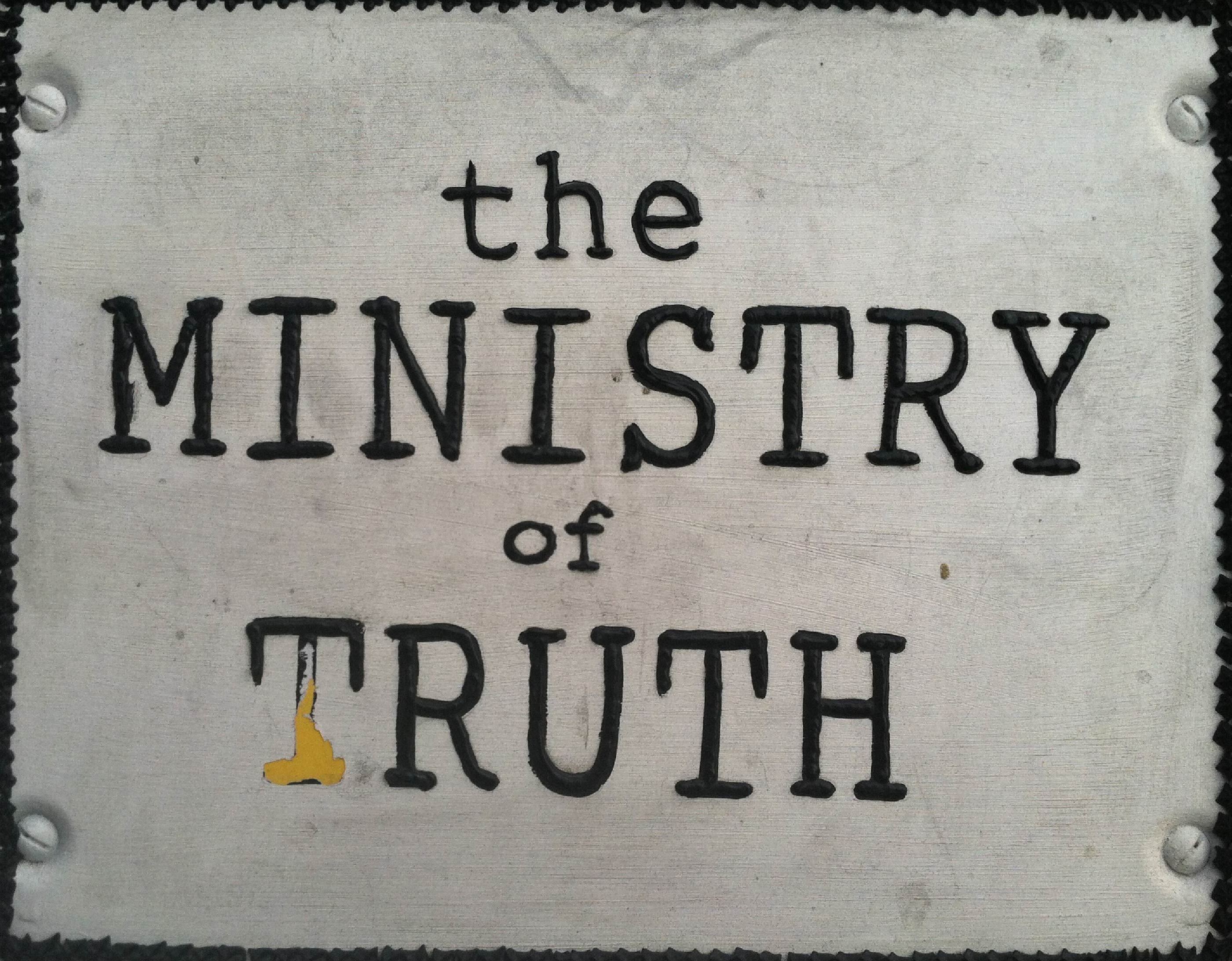

The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

Concerning the Beijing city campaign to regulate and purge illegal structures, all web portals immediately shut down related special topic pages, control interactive sections, refrain from reposting related content, and resolutely delete malicious comments. Print media must give prominence to policy reports, and stop independent focus on the topic. Non-local media cannot release related reports or commentary. (November 28, 2017) [Chinese]

Following a fire in a textile manufacturing district in southern Beijing that killed 19 on November 18, Beijing authorities launched a 40-day crackdown on unsafe dwellings. The ongoing crackdown has so far resulted in eviction for tens of thousands of migrant workers in the city, which according to the South China Morning Post has “sharply accelerated the authorities’ drive to move migrant workers out of the city as it tries to cap population growth.” While censors ordered media to follow official coverage of the fire, the disproportionate number of migrants that have been affected by the city campaign has stoked public outrage. Official denials that the campaign is targeting Beijing’s “low-end population” (低端人口)—a term earlier used in official documents to refer to the migrant population—has exacerbated public focus and outrage at the ongoing crackdown.

At Whats On Weibo, Manya Koetse translates excerpts from the media and online discussion of the evictions, noting comments on the official drive to control related discourse:

In “The Non-Natives After the Fire: Where Do We Have to Go?” [大火之后的异乡人:我们该到哪里去?] journalist Wang Shan (王珊) at Sanlian Life Week, an influential Beijing-based weekly news magazine, reports on November 26 that the Daxing area is a place where thousands of migrant workers from all over China live together.

According to Sanlian Life Week‘s report, there were plans to vacate the area before, but the big Daxing fire accelerated the plans. Residents did not receive an official announcement about when the evacuation was taking place and in a “race against time” had to collect their belongings and leave their homes or workshops behind.

[…] On Chinese social media, the evictions have become a major topic of discussion. Photos of people leaving their homes are widely being shared on WeChat and Weibo, although many netizens complained that their posts on this subject were being “harmonized” (censored).

[…] Some netizens, unhappy with the campaign, shared a video of the 2008 Olympics song “Beijing Welcomes You.” One video, posted on November 26, was shared over 2500 times in a day, receiving thousands of likes. “Beijing still welcomes you,” some commented: “It just depends on where you come from.” [Source]

At The China Collection, Donald C Clarke has translated a handwritten note by legal scholar He Weifang—who has turned to the archaic information sharing method after giving up social media due to the repeated harmonization of his accounts—in which He argues that “a harmonious city must have the complementarity of people of different income levels.”

At Radii China, Jeremiah Jenne compares the building safety crackdown that is affecting Beijing’s migrant population to another tragic Beijing news topic that authorities are working hard to regulate coverage of: alleged instances of sexual and physical abuse at a Beijing kindergarten. Jenne comments on how the official response to the two tragedies appear to impact members of very different socio-economic levels (although many middle class renters have also been caught up in the evictions). This, he suggests, may serve as a wake up call to those in the more privileged group:

It’s a dangerous game. There have long been grumbles by the moneyed class that many of the city’s problems are rooted in an overly permissive attitude to migrants from other provinces, foreigners, and the seemingly unregulated and chaotic neighborhoods popular with businesses run by members of these two groups. […]

[…] The child abuse scandal at RYB cuts to the heart of a sacrosanct — although mostly fictional — belief that economic success and relative wealth can protect the urban elite from the harsh realities faced by most other Chinese citizens. The urban elite believes they can spend their way out of life in substandard housing and provide their children the best education and healthcare money can buy. When policies affect their well-being or status, this group has also for many years consistently punched above its weight. But there are limits.

Chinese leaders, especially over the past 28 years, have perceived linkages — whether horizontal across geographical boundaries or vertically connecting grievances among social classes — as dangerous and destabilizing. The events of this week in Beijing, twin tragedies affecting different worlds in the same city, are sad reminders of realities often forced out of view by anxious authorities and the self-preserving elite. [Source]

We have four maps, based on clean-up notices collected online and from media coverage, showing how many neighborhoods/blocks are influenced by beijing’s latest expulsion: https://t.co/eV2GlECdkp #ddj

— Silva Shih 史書華 (@silvashih) November 29, 2017