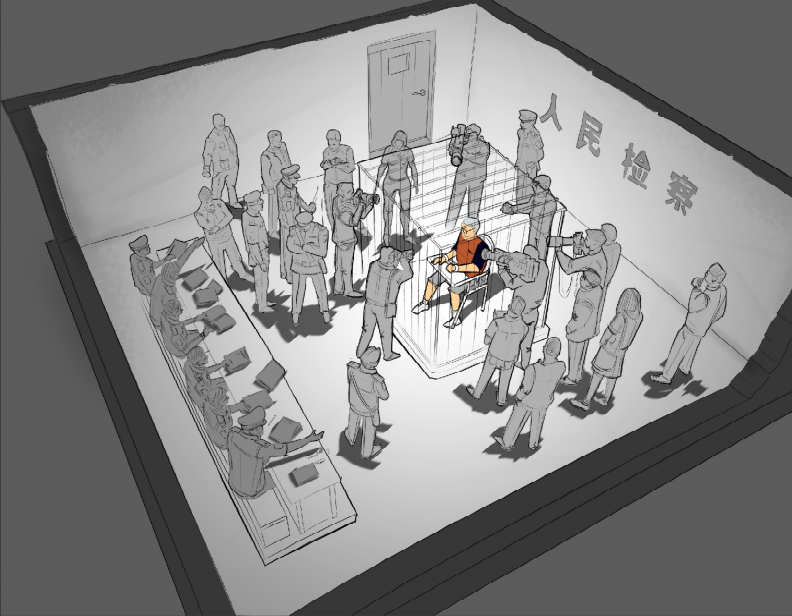

The past five years have seen growing alarm at the use of televised confessions, particularly in high-profile political cases. This week, Safeguard Defenders launched an in-depth report into the methods, motives, and consequences of these broadcasts. The report emphasizes the highly choreographed nature of the confessions, which are the product of close direction, tight scripting, calculated costuming, careful staging, intense rehearsal, multiple takes, and sometimes heavy editing. (As CDT has previously covered, this artifice extends beyond the detention center to the courtroom and social media.)

The report details some 45 confessions recorded since 2013, 60% of them by journalists, bloggers, publishers, lawyers, NGO workers, or activists. It draws on accounts from victims including “Black Friday” detainees, lawyer Wang Yu, her husband Bao Longjun, and lawyer Chen Taihe; Hong Kong-based bookseller Lam Wing-Kee and the daughter of his Swedish colleague Gui Minhai; British corporate investigator Peter Humphrey and Swedish NGO founder Peter Dahlin; and several pseudonymous rights defenders. It excludes both the routine broadcasts of confessions from ordinary criminal cases, and those produced by anti-corruption investigations under the Party’s internal disciplinary system, which is itself the focus of serious rights concerns. “Irrespective of the case,” it notes, “the broadcast of any confession on state or regional television should be regarded as a violation of human rights and the right to a fair trial and is equally condemned by Safeguard Defenders.” Most of the included confessions took place between 2013 and 2016, before the average rate of one per month slowed to just two in 2017, and one so far this year. The authors note that this decline has coincided with an increase in the broadcast of courtroom footage, including confessions, to achieve many of the same ends.

⁂

The report highlights three key motives for recording the confessions, particularly in rights related cases: to Deny, Denounce, and Defend. Some, like those of Gui Minhai, rights lawyer Xie Yang, and his alleged accomplice Jiang Tianyong, are intended to deny accusations of torture, kidnapping, or other mistreatment by the authorities that have spurred protest. “When the criticism is from overseas governments or organizations,” the report says, “the televised confessions become a foreign policy tool, that can either be viewed as a disingenuous effort on behalf of the Chinese state to refute the criticism or simply as a show of power.” Awareness of foreign viewers is also implied by the use of less overtly custodial settings and dress in rights cases, possibly “to ‘soften’ or disguise the coercive environment for a more critical overseas audience.”

“Denounce” statements include self-criticism or accusations against others, and “appear to be a deliberate attempt to discredit individuals or groups, such as human rights lawyers, activists, and bloggers.” Observers such as rights lawyers Teng Biao and Li Fangping and legal scholar He Bing have compared this forced self-criticism with the public shaming of the Cultural Revolution, with He quoted as saying that “the street parades of yesterday have become the televised parades of today. The political movement has overtaken the law.” (Zhu Zhengfu, deputy chairman of the All-China Lawyers Association, and senior judge Zhang Liyong are also cited as domestic critics of the confessions’ legality.)

The denunciation of others is particularly corrosive, leading to later suspicion and resentment among peers, however understandable the victims’ compliance or misleading the broadcast. While some may be more sympathetic, this itself further fragments communities by driving apart the two groups. (U.S.-based legal activist Chen Guangcheng has written elsewhere about the “divide and conquer” strategy behind the broadcasts.) Rights lawyer Lin Qilei is quoted warning against blaming the victims, saying that “if we make a moral judgment on the ‘confessor’ and accept the ‘confession,’ then we have […] fallen into the CCP’s plan.” But forgiveness can be difficult: journalist Zhao Sile, who highlighted the divisive effects of the confessions, said that “I have sympathy, but it’s also very hard for me to work with them again because I know that when they are interrogated or caught they may say my name.” (The transcripts in the report show the determination with which many victims avoid incriminating or denouncing their colleagues, however.) Wang Yu reports initially being mocked for her confession even by her own son and husband. In cases where the recording is not or is only partially broadcast, this threat continues to linger: as rights defender “Guo” wrote, “the recording must be sitting somewhere, collecting dust, ready to be used if they ever think it could be useful to discredit me, perhaps, or to ruin my reputation.”

“Defend” statements “are those that express support for the CCP or any of its agencies or actions,” and “may be aimed at reinforcing CCP legitimacy, a display of state power, or simply attempts to humiliate the detainees.”

Rights defender “Li” sums up the authorities’ motives for the confessions as follows:

The Party wants the detainee to incriminate themselves, to humiliate the detainee and make them look morally bad in front of the Chinese people, so they stop caring about the people who are detained. The detainees will lose their only source of moral support, and ultimately they can only end up being destroyed by the Party.

These TV confessions intimidate public intellectuals, they make everyone feel insecure, censor themselves, to never dare to say anything or do anything against the Party. It’s a white horror. [Source]

⁂

The confessions are typically obtained using promises of leniency or release; threats of worse treatment, death, or retaliation against family members or even lawyers; and deceit. These are sharpened through abuse such as sleep deprivation, intimidation, solitary confinement, stress positions, shackling, and beating.

Wang Yu was first surprised with a photograph of her son in detention, and then told that “my attitude would decide whether my son could be saved.” Threats against Xie Yang’s wife, daughter, brother, and nephew were used as leverage. Peter Dahlin was told that his girlfriend, a Chinese citizen who was also detained, would be held in torture-prone Residential Surveillance until he confessed.

The report cites several points in support of interviewees’ retractions and claims of coercion. Several victims were tried on different charges than the ones they had confessed to, or not tried at all despite the apparent gravity of their crimes, inconsistencies the report describes as “an indication that the charges themselves were fabricated and that the public confession was the price paid for freedom.” The report cites NYU legal scholar Jerome Cohen’s 2016 comment that “to say that [Wang Yu’s] confession was ‘probably’ the product of coercion is silly since she has been held in an intensely coercive environment for over a year.”

In case after case, detainees’ cooperation is secured under false pretenses. Many victims are told that the recordings are not for broadcast at all, but rather as “background research” or to help move their cases forward by persuading higher security or judicial officials of their contrition. Wang Yu, for example, was filmed the first time using a computer webcam, and told “you can see that we’re not putting you on television, if we were, we would be using a professional camera.”

⁂

The report also details victims’ efforts to navigate and mitigate the process. Several refused outright to denounce their colleagues as “criminals.” One insisted on only answering questions with questions when he suspected his captors were attempting to gather footage, in order to make it impossible to edit into a plausible confession. Peter Humphrey wrote that he tried to speak only in conditional sentences—saying that “if I had violated the law […] that I did so unknowingly and I’m sorry”—an effort he believes was thwarted by heavy editing. Peter Dahlin describes his eagerness to include the scripted confession that he had “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people,” to the extent that he repeatedly stumbled over the line. “I knew for sure that including that incredibly crass line also meant that the media frenzy would go into overdrive. Everything else they wanted me to say would be negated by that one line. I might as well say: ‘I’m being forced to do this against my will, and no one has any reason to believe any of this is true.'”

Besides the loss of trust and fragmentation of communities, victims are left with the psychological marks of “an intensely distressing and humiliating experience.” Peter Humphrey told the authors that more than four years after his confession, it “figures very high in my post-traumatic stress disorder syndrome. It is one of those horror moments that often comes back to me and upsets me even now.” Wang Yu reported that “I am still struggling to get over the trauma.”

A particular focus of the report is the role of the media in the confessions’ creation and propagation. While state broadcaster CCTV is their main distributor through its various national and local channels, state-funded news site The Paper and Hong Kong’s Phoenix TV and Oriental Daily have also carried them. South China Morning Post receives particular scrutiny as “the first English-language, non-state media that collaborated with the Chinese police to circulate a televised confession.” This, and particularly its distribution of Gui Minhai’s third confession in February, was a central complaint by critics in the online debate following a recent New York Times article on Beijing’s influence over the now mainland-owned paper. Safeguard Defenders also warn that other media could also become complicit if they relay confessions without qualification. Dahlin addressed this in a separate op-ed at Hong Kong Free Press, coinciding with the report’s launch:

So how should responsible media report on Gui’s, and all the other forced TV confessions? It certainly needs coverage, and such coverage is key to exposing how China is undermining the international rules-based system we have for long taken granted. It’s also key to put the spotlight on the victims, like Gui.

Continued coverage will also certainly help the growing calls for the EU to sanction Chinese media just like is has with Iranian media, and push the U.S. to treat Chinese media the same way it now treats Russian state-backed media. Coverage is key.

However, responsible media should not let themselves be played as pawns by the CCP. They should not focus on the words of the confession – which we all know are not Gui’s words – they are the words of the CCP. Those words should simply be ignored, and certainly not quoted, as they have no value of any kind, and to reprint them simply serves the purpose of the CCP.

The next time China airs a forced TV confession – pre-trial and probably even pre-arrest, the media should report it with responsibility and humanity and report it for what it is – a repugnant violation of both human rights and the right to a fair trial. [Source]

There should be no doubt after reading this report that China’s televised confessions are gross violations of both domestic law on the right to a fair trial and basic international human rights protections. There should also be no doubt that they are staged theatre, written and directed by the police with the cooperation of the media. From our analysis of what suspects are forced or manipulated to say, and when they say it, there is also little doubt that China is using these televised confessions as a propaganda weapon for both domestic consumption and as a foreign policy tool for an overseas audience.

There is little to distinguish them from the repugnant practices of Mao-era public struggle sessions or Stalin’s infamous show trials. Interviews for this report revealed how the confessions are extracted through torture, beatings, threats and fear. The fact that media collaborate does not just reflect a shocking lack of journalistic ethics but direct culpability with this outrageous abuse of human rights of both Chinese citizens and foreign nationals. Furthermore, China’s use of forced televised confessions warrants urgent global attention as Beijing steps up its aggressive push to globalize its state media—including on social media channels banned at home—to “tell the China story”.

Scripted and Staged: Behind the scenes of China’s TV confessions reveals these confessions for what they really are: systematic and widespread abuses of human rights to serve the political interests of the CCP. Our recommendations are:

• The People’s Republic of China: should immediately halt the use of televised confessions, provide all detainees with the legal protections already enshrined in domestic law and review the existing legal framework to prevent further violations.

• Overseas governments: should unequivocally stress to the People’s Republic of China:

- the need for stronger protections in law and in enforcement for due process; o that it must immediately cease broadcasting televised confessions of detainees;

- that there will be consequences for ongoing violations of fundamental rights and freedoms.

• International media has an obligation to ethically and responsibly report on China’s televised confessions, by exercising caution and adding crucial background that explains how the practice violates both Chinese law and international human rights protections; that threats and torture are routinely used as coercion; that they are often scripted and staged by the police; and that they are very likely a vehicle of Party propaganda.

• Immediate action should be taken against Chinese media responsible for the broadcast of televised confessions. This report identifies CCTV and its channels – CCTV1, CCTV4, CGTN (formerly known as CCTV9) and CCTV13 as the main vehicles for China’s televised confessions. Recommended actions are:

- Utilize the Foreign Agents Registration Act (in the US) and equivalent in other countries, to force CCTV and responsible media to register as a foreign agent.

- Utilize existing tools to sanction (travel bans and asset freezes) on key CCTV executives. This would follow similar action taken on Iran’s Press TV in 2013 by the EU after its broadcasts of forced televised confessions.

- Introduce Magnitsky-style legislation in jurisdictions without a Magnitsky Act, and use that to pursue further action on all CCP-owned or controlled media, including CCTV. [Source]