Baozou Big News Events (暴走大事件), a “rage comic“-inspired Chinese internet variety show that has swelled in popularity in recent years, has been silenced along with other providers of the genre following the reposting of a four-year-old clip now considered illegal under a new law. The newly passed law, the Law on the Protection of Heroes and Martyrs, went into effect on May 1 and is seen as a the latest in a series of moves by the Xi administration to combat “historical nihilism,” or attempts to question the Party’s sanitized account of the past. At Sixth Tone, Lin Qiqing reports on the clip that violated the law, and the variety show’s (referred to as Baozou Manhua by Sixth Tone) subsequent censorship on Chinese platforms, and other recent punishments under the new law:

The accusation relates to a 58-second Baozou Manhua video clip that was posted to content aggregator Jinri Toutiao earlier this month. First released in 2014, it joked about two Chinese civil war figures: Ye Ting, an army general, and Dong Cunrui, a People’s Liberation Army soldier who destroyed an enemy bunker in a suicide bombing.

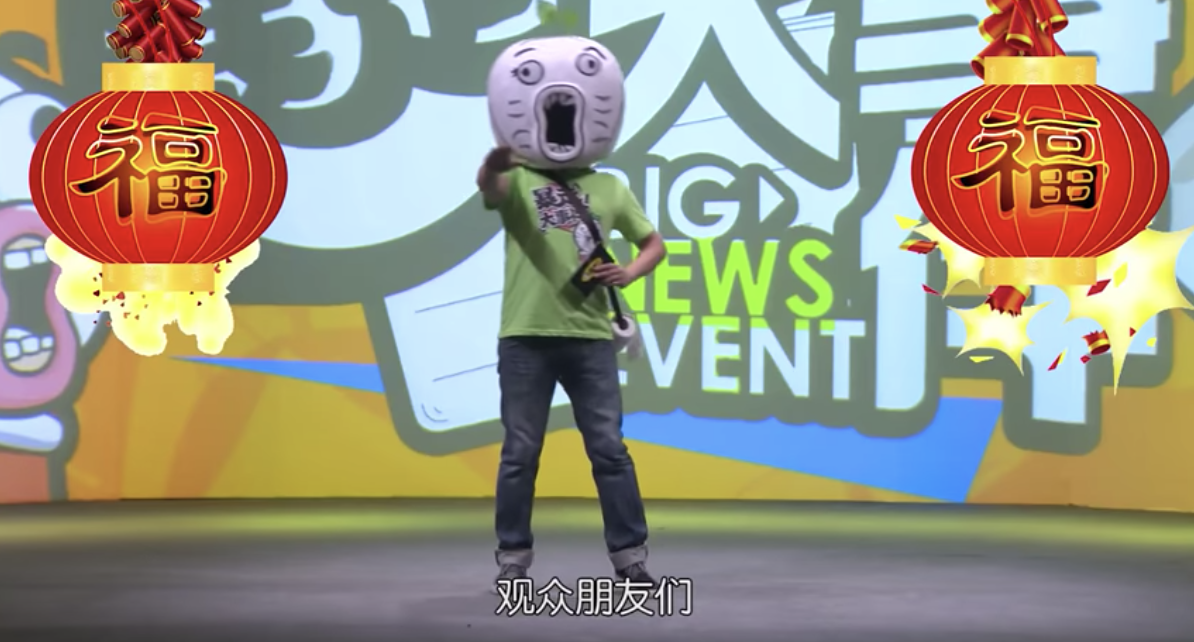

In the clip, host Wang Nima dons a rage face mask and narrates: “Dong Cunrui stared at the enemy’s bunker, his eyes bursting with rays of hate. He said resolutely, ‘Commander, let me blow up the bunker. I am an eight-point youth, and this is my eight-point bunker.’” The script was a pun on a KFC sandwich available for a limited time in 2014.

[…] Baozou Manhua is not the only target of China’s ramped-up history wars. Several people have been detained this year for making disrespectful remarks about the Nanjing Massacre, and Weibo announced that it had shut down 16 accounts — including Baozou Manhua — for joking about civil war and Korean War martyrs.

Baozuo Manhua CEO Ren Jian issued a public apology on Thursday. “The company will start internal rectification from today,” the statement said. “We’ll stop posting new content and organize for all of our staff to learn relevant laws and regulations.” [Source]

Jinri Toutiao, the popular aggregator where the 2014 sketch was shared this week, was ordered to shut down several entertainment-focused social media accounts early this year as internet media regulators expanded their jurisdiction over online news.

At Whats On Weibo, Manya Koetse reports on the massive growth in popularity of rage comics in China, spurred on largely by the efforts of Wang Nima and his recently censored brand, and translates netizen commentary on the censorship:

Baoman became more popular in mainland China when ‘Wang Nima’ (@王尼玛 on Weibo) launched the website baozoumanhua.com (now offline) in 2008, inspired by the success of the webcomics on English-language online communities (Chen 2014, 690).

[…] In 2012, the website officially registered the copyright of their Baoman products, as baozoumanhua.com started receiving 5000 to 8000 daily submissions of new comics (Chen 2014, 692-695); Chinese ‘rage comics’ then also became more widespread on platforms such as Weibo or Wechat, where these ‘rage faces’ are commonly sent as emoticon-like stickers during chat conversations.

[…] According to baozoumanhua.com founder Wang Nima, the Baoman genre provides Chinese gao gen (grassroots) netizens “a ‘lance’ to express themselves” (Chen 20154, 693); meaning this kind of humour can also serve as a frivolous way of resistance, using humor as a weapon to talk about daily frustrations.

[…] Although sarcasm and crudeness are very much inherent in the Baoman humor, this does not mix well with the new law that has recently been implemented in mainland China to ‘protect’ its national heroes. […] [Source]

Netflix recently paid $30 million for streaming rights to an English version of the Chinese computer animation film Next Gen, which is based on a rage comic by Wang Nima and bankrolled and produced by Baozou. It is currently unclear whether Wang’s current legal troubles in China could affect this deal.

The apparent targeting of rage comics may be difficult to effectively enforce. As of now, only channels known to distribute similar content have been targeted. The user-generated, memetic nature of the genre, along with its reliance on humor and sarcasm, likens it to the resistance discourse long used by netizens to ridicule and skirt censorship online. CDT maintains the Grass-Mud Horse Lexicon, a glossary of the memes, nicknames, and neologisms created by Chinese netizens and encountered in online political discussions. See also CDT’s translation of a Baozou Big News Events sketch on privacy in the era of big data from last month.

For more on the rise of rage comics and “facial expression” (表情 biǎo qíng) memes in China, see a 2016 field guide by Christina Xu at VICE.