Beijing-based women’s rights activist Xiao Meili recently introduced her friend Ma Hu with the first part of a three-part profile. Part one told the story of Ma Hu’s childhood, and how she dealt with her gender and sexual identity in a society that offered serious pressure for conformity on both fronts. CDT has translated part two, which tells of Ma’s experiences in Beijing, where she filed a lawsuit against China Post for gender discrimination, and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. All bold text was carried over from the original Chinese WeChat post. CDT will translate the third and final part of this profile shortly after Xiao Meili posts it. The essay begins as Ma Hu accompanies Xiao Meili on her 2013 protest walk:

I’m sorry to have kept you all waiting for so long,

And I’m sorry that The Story of Ma Hu will have a third part. There are just too many things I want to tell.

Later, I asked Ma Hu: “What was your first impression of me?”

Ma Hu said: “This person is so tanned!”

“I saw your picture online and thought you were tall, but not so much in person.”

“And then I saw your hands—so small.”

“They Seemed So Fascinating to Me”

[…] Ma Hu was drawn to this life where she could walk all day without talking. She thought it was very healing. “Henan braised noodles are so delicious. And, there are people who like eating raw garlic! Yes, you! Hahahaha. I felt at ease. In my hometown, only rural folks eat raw garlic. You’d be laughed at.”

There were friends who joined and left the Walk at different points. We were treated to two great banquets by people from Zhumadian [Henan], the so-called worst people in China. They also let us stay for two nights free of charge. We walked by empty towns and endless piles of trash. We walked by many coffins at night (Ma Hu remembered this vividly but I completely forgot). We walked from the greyish north to the greenish south.

As we arrived in Wuhan, we were welcomed by friends from Guangbutun Feminist and Lesbian Group. They helped arrange all sorts of lectures and sharing sessions in Wuhan. These girls, who were the same age as us, started this group on their own and gave it quite a rustic name. The group was completely volunteer-based and they were doing it out of their passion. Ma Hu didn’t talk much. She watched with curiosity: “I would love to hang out with these people. They seemed so fascinating to me. I would like to do something like this in the future, even if the conditions aren’t good.”

Did the Walk Change You?

And further down south, an internet friend called Mu Lan was the next one to take us in. Mu Lan and her husband didn’t want any children. On the day she came to see us, she had just been scolded by the seniors in her family for being anti-humanity. She majored in gender studies. Many of her classmates thought the best situation was “being able to both dive into the studies and also get out”: You follow the gender theories when you’re doing academics, but you live your life as it is. They thought Mu Lan was “diving in too deep.”

I had a great conversation with Mu Lan, but Ma Hu didn’t say a word. I was worried that she had been bored. Many years later, she told me that this conversation left a deep impression on her: “Although Mu Lan couldn’t step out to do things publicly, she has always been supporting us in her own way.”

Forty days had passed, but Ma Hu wanted to keep walking until the end. For a while, she was conflicted and worried that others might think she wanted to stay because she was in a relationship with me. But she was so drawn to this Walk. She thought this this was not only performance art, but also a form of resistance and assembly that could simultaneously help people in a real way. In the end, she walked with me for 104 days until we reached our destination, Guangzhou.

“Did the Walk change you?” I asked Ma Hu. She said: “Yes, I was absorbing things along the way. I felt my mind was made clearer. But at the time I didn’t yet connect the feminist perspective with my own life experiences… After that, I no longer wear my chest binder. During the Walk I realized people actually had the option not to wear a bra or chest binder.”

And after a while, Ma Hu said: “It was hard for me. I used to have a hard time discovering people’s kindness. I was disoriented at the time. And I ran into all these people, some of whom were feminists, and others simply strangers. And they were all very kind.”

Caochangdi Art District

After the Walk, I went back to Beijing and Ma Hu came along too. Looking for cheaper rent and a freer, more artsy atmosphere, we decided to move to Caochangdi Art District.

Just after we arrived at the destination, the mover asked while squatting in front of the alley, smoking: “What the hell is this place. There isn’t even cell phone reception. How much are you paying for this? … 1500 yuan?” Then he clicked his tongue and shook his head, as if we were two fools.

Caochangdi is an urban village located near Beijing’s Fifth Ring Road. Half of the village is art space. There are spacious red-bricked houses, the bricks exposed on purpose. The villagers thought these houses were unfinished, and that the builders ran out of money to cement the walls. The other half of the village is filled with self-built houses where migrant workers live. These houses are densely built, with very narrow spaces in between. At first sight, it looks like a miniature Hong Kong, but unfortunately the people are not scaled down. The cell phone reception was indeed bad—I had to climb to the rooftop everytime I needed to make a phone call. There were always so much poop in the alleys, and I’m not sure if it was from dogs or humans. Outside of the village, there is a long overpass that leads to the spaceship-like Wangjing SOHO. Beijing is like that, people living such different lives on the same piece of land.

(Source: Xiao Meili)

“I’m Going to Beijing!”

Ma Hu wanted to become an artist but didn’t know where to start. Having graduated only a short time ago, she wasn’t particularly worried. She wanted to gather some more experience. She found a job at an art auction house. Her daily duties were making phone calls to painters in the second and third-tier cities, most of whom were old men, and asking whether they wanted to auction off their paintings, then asking these same people to buy the paintings for a high price. That way, the auction house could collect service fees and the painters could claim their works were worth big bucks. “It was a rough job. Why did I do something like that?”

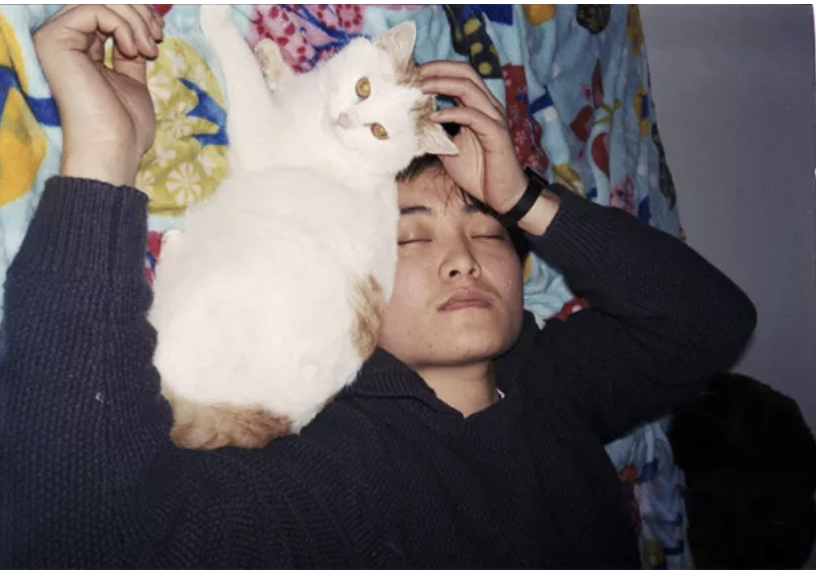

Ma Hu in Beijing (Source: Xiao Meili)

After she quit, Ma Hu looked for jobs at some painting studios but liked none of them. She became more of an introvert. She no longer wanted to go dancing with me at the art studios that we used to frequent. She didn’t want to attend my speeches. When I went to claim the Women’s Media Award, she adamantly refused to go.

The most excessive incident came when a friend asked us to have hotpot together. We prepared beef slices and lamb slices, but when we were on our way to the friend’s place, she went straight home as we walked past our apartment building. I tried to persuade her to go, but she just wouldn’t. She ended up not going. When she was not happy, she would not answer any of my questions. She was more stubborn than a donkey. This made me feel mad and powerless.

Ma Hu in Beijing (Source: Xiao Meili)

Later I asked her: “So what was with you at the time?” She said: “I thought I was trying to escape, I didn’t want to face a sad life. I didn’t know what to do, and I thought you were trying so hard. It was not that I didn’t want to meet people. It was because you were famous, and I didn’t want to be remembered as your girlfriend. And perhaps I was trying to control you. I was insecure.”

Ma Hu wanted to step out of the predicament. She wanted to get more experienced with society and do something down-to-earth.

She saw couriers in the village going around on their tricycles and she thought of joining them. Couriers have relatively more freedom. They could meet many people and maintain a certain distance at the same time. They could weave through this folded world.

Seven Tests for a Female Courier

1) Although China Post’s job ad said “male only,” Ma Hu still sent in an application, just in case she was selected. She was invited to an interview that same day.

2) The HR manager who interviewed Ma Hu said: “There has never been a woman courier before. We don’t hire girls.” Ma Hu said: “Just let me try.” She is very persistent. The manager couldn’t make the decision and took Ma Hu to the director.

3) The director thought Ma Hu, being a girl, was not able to work as a courier. Ma Hu badgered the director for quite a long time, until finally he gave in and said: “Come and try it out tomorrow then.”

4) On the day of her trial, a courier took Ma Hu to the 798 Art District route. Ma Hu and the courier dropped off and picked up packages together. “It was so hip. And people on street thought it was quite interesting to see a girl courier.”

After the trial, the director asked Ma Hu how she liked it. She said: “It was good, not too tiring.” But the director still tried to talk Ma Hu out of it. Ma Hu asked him to give her another day.

5) The next day, Ma Hu followed another courier to a district near 798. At lunch, the courier also tried to talk Ma Hu out of it: “You’re a little girl, why don’t you find another job? This job isn’t for you. Don’t do it.”

A gatekeeper knew this courier well. He saw him with Ma Hu and mistook her for a boy because she dressed in tomboy style. The gatekeeper said to the courier: “Wouldn’t it be cool if you had a chick with you?” The courier said: “Actually she is a girl.” The gatekeeper went silent, and Ma Hu felt upset.

After the second day, Ma Hu told the director that she felt good about it and was confident she could do the job well. The director said: “Go get a physical checkup, send in your resume, and wait for notice.” Ma Hu thought she had succeeded. She thought she had finally become a courier after all her hard work, and she was very happy.

6) After submitting her application, Ma Hu bought a Thermos lunchbox and water bottle, and a back support wrap. She was ready to be a courier. She had friends who suggested other jobs but she declined. She thought she may get the offer from China Post at any minute and would have to start working.

After waiting for 10 days without hearing anything, Ma Hu called China Post. The director’s secretary answered her call and said the director went to the hospital, and that Ma Hu’s application was still sitting on his desk, waiting to be turned in.

7) Another week passed with no progress. Ma Hu called again and was told: “Your application was rejected by headquarters. Headquarters said frontline staff (couriers) just can’t be female.”

After being rejected, Ma Hu was furious and decided she had to sue

- In 2013, Cao Ju filed the first lawsuit involving gender discrimination in employment. It took one year for her case to be accepted by the court.

- In 2014, the case of Huang Rong took one month to be accepted by the court.

- In 2015, the case of Ma Hu took 2 days to be accepted by the court.

- In 2016, the case of Gao Xiao was accepted by the court on the same day.

Toast to Freedom

In March 2015, the March 7 Feminist Five Incident happened, and five of our friends were taken by the police. The five feminist activists were simply planning to distribute anti-sexual harassment flyers at subway stations before International Women’s Day. They were not able to carry out this mild and routine activity before police from three different regions burst into their homes and took them to jail. They were jailed for 37 days.

For a while, I was blown away. Then I felt sad. I felt as if we were jailed ourselves because we were doing the same thing. Ma Hu and I wanted to post some pictures to show support. We wrote down the poem by Qiu Jin on a piece of paper: “Our generation loves freedom. Let’s make a toast to freedom.” Taking pictures with this piece of paper in my hand, I murmured this poem in my heart and couldn’t help but burst into tears.

I was getting ready to leave Beijing because I had no idea why they were rounding people up, or whether they might come after me. I asked Ma Hu whether she wanted to leave together. She said that she should be fine, that she had this ongoing lawsuit, and that she had a cat to take care of. But it was mainly because she didn’t have the money to leave.

The time they spent in jail was torture for all my friends. Every second, we were guessing and waiting, wanting to do something to help but not knowing how, and not daring to take any actions. Ma Hu met with the friends who stayed in Beijing from time to time. Then came Day 37—the maximum time allowed by Chinese law to detain a citizen without a reason. Everyone who cared about this was waiting anxiously: Will they be able to get out or not? To vent off anxiety, Ma Hu and friends put up a giant piece of paper on the wall. They wrote on it incessantly until it was all filled up.

(Source: Ma Hu)

First Court Case

On the day of the first hearing [of Ma Hu’s gender discrimination case against China Post], our five friends were still in jail. Ma Hu posted the notice of her trial on Weibo, and then deleted it. She didn’t want to make a big noise. Our friends were all scared, and Ma Hu was worried that the lawsuit might be affected. Ma Hu said, at court, “I opened the door and, oh wow, there was a big crowd. I was even more scared.” The 20 or 30 people who came were all young women. There were many people who cared about this case.

The opposite side had a terrible attitude. During the hearing, they stood up many times, cursed at Ma Hu, and said that she had malicious intent: “You are a college graduate who studied oil painting, why would you want to be a courier? This must be an trap.” “You just want to make a hype to get famous.” “Being a courier is a very taxing job. It’s just not for women.” And the judge kept saying: “Sit down, calm down, stop bickering.”

Ma Hu saw her experienced attorney, L, go purple in the face. Ma Hu said: “They think they are powerful, don’t they? They are a state-owned enterprise, like they can curse however they want and nothing will happen to them because they have strong backing.” “Their evidence was poorly prepared. They just kept scolding us, wanting to crush us with their threatening manner.”

After the hearing, a TV station wanted to interview Ma Hu. Ma Hu was scared and felt wronged after being scolded for hours. And her friends were still locked in jail. Many other friends didn’t dare come to court. Ma Hu shouldered all of this and couldn’t speak up. In front of that big and alien TV camera, she burst into tears.

Later, many media came to interview her. Introverted Ma Hu was more than willing to answer their questions. She wanted to tell people that many women were discriminated against in employment, and that we needed to fight for our rights. “The more people know about this, the better. Otherwise the lawsuit will be a waste of time.”

Ma Hu in Beijing (Source: Xiao Meili)

Ma Hu Becomes Grandpa Ma

After pulling through the March 7 Incident and the fierce phase of the lawsuit, Ma Hu noticed that something was wrong with herself. Ma Hu didn’t know when it started, but she felt spiritless every day, always lying on the couch. She couldn’t get up in the morning. Even if she was awake, she couldn’t get up.

For more than 10 days in a row, Ma Hu didn’t go out, and she didn’t eat much. She lost so much weight that she was disfigured. She was not able to stand up for too long and had to squat down and rest. She still had her mind set on the lawsuit. It pained Attorney L to see Ma Hu like this: “Oh dear kid, you can’t even get up from the ground.”

Ma Hu didn’t notice that what was happening to her was quite abnormal. She didn’t tell her friends what was going on, and her friends didn’t know much about depression. They thought she might be physically ill and didn’t take it seriously. Ma Hu’s movements were so slow that climbing stairs would leave her panting like an old man. Her friends jokingly called her “Grandpa Ma.”

Ma Hu in Beijing (Source: Xiao Meili)

Unsatisfactory Victory

When the second trial began, our five friends had been released and sent back to their hometowns. Li Maizi was from Beijing and she went to see Ma Hu at court. They hadn’t seen each other for so long. Ma Hu thought Li Maizi seemed to be in good spirits, and so finally she could stop worrying about her too much. Ma Hu said: “I hugged her and I thought, oh my, that feeling of friendship.”

Ma Hu was bothered by her own personality and thought she could not connect with others well, and that she could not interact with others as friends. But at that moment, Ma Hu deeply felt her membership in the group. “That hug was very crucial. It gave me great courage to carry on.”

Six months into the lawsuit, with help from friends, NGOs, kind-hearted lawyers and the internet, Ma Hu finally got a verdict from the court: A victory. The ruling said in clear terms: “China Post engaged in discrimination against the plaintiff.” And the court ruled that delivery is not an industry that females cannot participate in.

Ma Hu wasn’t happy about this ruling. It didn’t require China Post to apologize or order it to pay the court fees and notarization fees, merely ordering 2000 yuan in compensation. 2000 yuan. This is how cheap it is to discriminate against a girl. And how much does it cost to win a gender discrimination lawsuit? Ma Hu appealed. The process went ever more slowly. And the case hasn’t reached its final verdict yet.

“This lawsuit is very empowering. It is down-to-earth. I didn’t want to be an artist anymore. I didn’t want to do social activism either. I just wanted to carry on with this lawsuit.” Ma Hu started to learn more about the employment discrimination cases from before, and problems faced by women in the labor force. She more personally felt the situation of women in this society. Later, Ma Hu joined an NGO dedicated to help women in the labor force, hoping to help more people facing gender discrimination.

Giving up Physical and Mental Health

Ma Hu in Beijing (Source: Xiao Meili)

From March to April, Ma Hu wasn’t able to take care of herself. She didn’t eat much, didn’t wash her face or brush her teeth. She used to be a bit of a hygiene freak and couldn’t stand herself like this.

From May to June, Ma Hu started to hook-up a lot, wanting to prove that she was in control of her life and that she could live well. She didn’t sleep at night but she was energetic. She didn’t have money but still wanted to spend. She bought all these nonsense things, hoping to gain the sense of control by shopping. Ma Hu said: “This was also a common manifestation of mania.” For a while, she was overeating and gained 20 jin [about 26 lbs] in one month. Her body was like a balloon that inflated and deflated following her acute mood swings.

In the winter of 2015, Teacher W from social work studies started a counseling support group in Beijing. She invited a very experienced psychology professor, hoping to help people who went through the March 7 Incident. At the first group meeting, participants were all sharing their experiences and feelings. Ma Hu didn’t say a word the entire time. She didn’t want to talk about herself, didn’t want to look back, didn’t want to return to the state of mind she was in during March 7, and didn’t get what others were talking about. The professor was quick to notice something was wrong with Ma Hu. She chatted with Ma Hu privately, and asked Teacher W to take Ma Hu to the doctor.

Sure enough, she was diagnosed with manic-depressive disorder, AKA bipolar disorder. The doctor said, for a situation like yours, we’d recommend hospitalization. It’s been nine months and you’ve missed the best time for treatment. Ma Hu didn’t take it seriously. And she didn’t want this to affect her job so she refused hospitalization but started taking medication.

At first, her body couldn’t take so many medications. She threw up for days. And because she didn’t want to eat much, in the end there was nothing to throw up. She felt dizzy. She couldn’t even walk to the living room from her bedroom. Taking pills made her feel perplexed. It was like giving up everything, her mood, her body, for the doctors to decide whether they were normal or not.

Ma Hu in Beijing (Source: Xiao Meili)

“I’m Not Going Out”

Ma Hu was stubborn: “I can’t let people think that I won’t be able to do anything with this condition. I have to do my job well and on time.” She didn’t know how to seek help. She didn’t tell people that she felt ill. She didn’t want to bother people and tried to take on everything by herself.

Her friends didn’t know what to do either. They didn’t want to give her any more pressure. In Beijing, Ma Hu worked from home and didn’t go out that much. When her roommate invited friends over, Ma Hu hid in her bedroom. One time, a friend sent Ma Hu a WeChat message from the living room: “Ma Hu, come out.” She replied: “I’m not going out.”

Ma Hu in Beijing (Source: Xiao Meili)

Everything Seemed Hopeful

The rent in Beijing was too high, and suddenly increased by 500-600 hundred yuan. Ma Hu couldn’t afford it. She thought of the many friends she had in Guangzhou and wanted to move there. “I arrived in October and didn’t expect Guangzhou to be that hot.”

After working for long, Ma Hu started to communicate with more lawyers, plaintiffs and volunteers. And she took many interviews. She was more outgoing than before. “But I was wrestling with myself. I really wanted to tell which emotions belonged to me and which stemmed from the illness and the pills.”

Ma Hu was learning something from every follow-up session with her doctor. She memorized the doctor’s questions and how to answer them. She paid attention to her emotions and conditions, and learned what these conditions were like, how long they lasted and what the triggers were. Gradually, Ma Hu was able to notice her condition and make adjustments.

For example, Ma Hu would still want to spend money during her mania phase, but was able to control herself. Whenever she wanted to spend money, she would go to the supermarket, at least that way she could get herself to eat more. “Once I bought a couple of things from your family’s store. I thought if I had to spend the money, I may as well spend at your place. At least that could help you earn a buck or two.”

Ma Hu had a new girlfriend. The medications made her a bit stiff and dull. She didn’t want to be like that. She was starting a new life. Everything looked hopeful. So she just stopped taking her medication.

Translation by Yakexi. Stay tuned for CDT’s translation of part three of this profile.