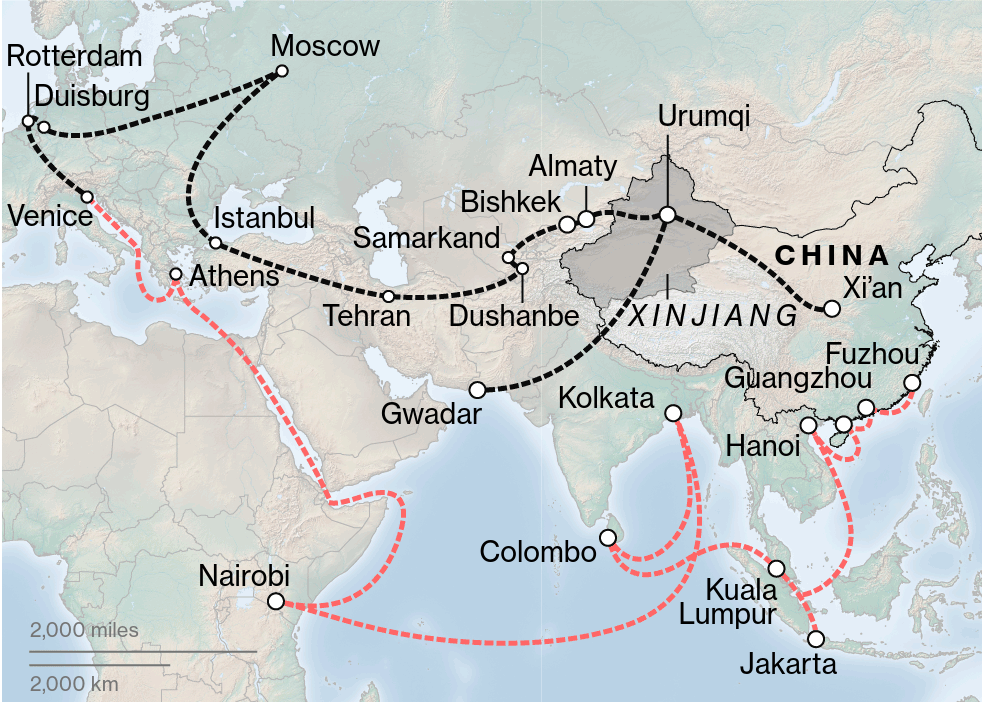

Xi Jinping’s massively ambitious infrastructure investment plan, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has long been controversial, raising concerns over for its potential to create debt traps, erode national sovereignty, exacerbate local security risks and human rights abuses, or otherwise unequally benefit Beijing. Last month, Italy became the first G7 nation to formally endorse the initiative, a move that prompted quick protest from the E.U. and the U.S. As controversy continues to mount around the plan and Beijing prepares to host its second Belt and Road Forum later this month, the Center for a New American Security has released a report including a checklist to use in assessing the associated risks of a BRI-related project. The report’s executive summary outlines the seven potential challenges that should be considered by a recipient state before signing on to a BRI project:

-

Erosion of national sovereignty: Beijing has obtained control over select infrastructure projects through equity arrangements, long-term leases, or multi-decade operating contracts.

-

Lack of transparency: Many projects feature opaque bidding processes for contracts and financial terms that are not subject to public scrutiny.

-

Unsustainable financial burdens: Chinese lending to some countries has increased their risk of debt default or repayment difficulties, while certain completed projects have not generated sufficient revenue to justify the cost.

-

Disengagement from local economic needs: Belt and Road projects often involve the use of Chinese firms and labor for construction, which does little to transfer skills to local workers, and sometimes involve inequitable profit-sharing arrangements.

-

Geopolitical risks: Some infrastructure projects financed, built, or operated by China can compromise the recipient state’s telecommunications infrastructure or place the country at the center of strategic competition between Beijing and other great powers.

-

Negative environmental impacts: Belt and Road projects in some instances have proceeded without adequate environmental assessments or have caused severe environmental damage.

-

Significant potential for corruption: In countries that already have a high level of kleptocracy, Belt and Road projects have involved payoffs to politicians and bureaucrats. […] [Source]

Covering the CNAS report, Bloomberg News notes one particularly problematic case study it analyzed:

The analysts reviewed 10 Chinese infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative across Asia, Middle East, Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Pacific islands to generate the list of challenges and the respective challenges.

As an example, Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar is presented as a nexus of all seven problems, with a contract locking in operating rights for the port to a Chinese firm for 50 years. The deal was sealed at the last minute without public debate and granted China direct access to the Indian Ocean, according to the report.

China is aware of such challenges and criticism. The government is drafting criteria for overseas investments to be considered part of President Xi Jinping’s signature program as it works to counter the international criticism, Bloomberg reported. U.S. Vice President Mike Pence warned Asia-Pacific countries in November against taking China’s money, adding that the U.S. wouldn’t “offer a constricting belt or a one-way road.” [Source]

See also a Bloomberg TV interview with report author Daniel Kliman on the criteria leaders should be examining before entering into a BRI contract.

The Hindustan Times reports on a new line of BRI criticism coming from the U.S., where Chief of Naval Operations John Richardson this week told members of the House Armed Services Committee that “China’s Belt and Road Initiative in particular is blending diplomatic, economic, military, and social elements of its national power in an attempt to create its own globally decisive naval force”:

“China’s modus operandi preys off nations’ financial vulnerabilities. They contract to build commercial ports, promise to upgrade domestic facilities, and invest in national infrastructure projects,” he said.

[…] “In the final analysis, these unfavourable deals strangle a nation’s sovereignty -like an Anaconda enwrapping its next meal. Scenes like this are expanding westward from China through Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Djibouti and now to our NATO treaty allies, Greece and Italy,” he told members of the House Armed Services Committee.

[…] China and Russia are determined to replace the current free and open world order with an insular system, Richardson asserted.

“They are attempting to impose unilateral rules, re-draw territorial boundaries, and redefine exclusive economic zones so they can regulate who comes and who goes, who sails through and who sails around. [Source]

At Foreign Policy, Andreea Brinza looks at China’s “16+1” mechanism in Central and Eastern Europe, noting the lingering frustration that resulted from Beijing’s poor communication, undelivered promises, and suspicions of a veiled bid for political influence. Brinza analyzes the 16+1 experience wondering if it could be used to predict the future of the BRI:

[…S]even years in, as participants gather for the annual 16+1 summit in Croatia, those hopes are already faded. China failed to make its intentions clear, failed to deliver on many of its promises, and failed to offer the assurances its partners needed. In turn, the European Union—which includes 11 out of the 16 countries involved—has increasingly criticized China’s role on the continent. The failure of the 16+1 may offer a vision of the future of the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s grand geopolitical plan.

The EU saw the 16+1 format as an attempt by China to divide the union by offering investments to less-developed EU members in exchange for political influence. The launch of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 and the subsequent wave of publicity, as the program came to dominate both Chinese media and global worries about Beijing’s rise, added to these tensions. The EU started to feel under siege.

China’s intentions may have been good, but Beijing failed to communicate them clearly, leading to EU opposition toward the 16+1. China’s choice was a manifestation of its penchant for regional diplomacy, typified by other forums such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation or the Forum of China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States.

But China failed to articulate a clear vision on the nature of the 16+1 (whether it was just a grouping or an attempt to create an organization with permanent institutions) or its investment strategy and objectives in Central and Eastern Europe. […] [Source]

At Nikkei Asian Review, Zach Coleman reports on a statement from a transportation executive familiar with the Asia Pacific region on how BRI projects are so far having only limited impact:

“I think the implementation has been slower than what had been expected in the beginning,” Gregory Enjalbert, vice-president of Bombardier Transportation’s Asia-Pacific rail control solutions, told the Nikkei Asian Review in a recent interview.

“In most places, [there] has not been much of an impact at this point,” said Bangkok-based Enjalbert. “I think there is still a lot to be done in terms of real project implementation.”

[…] In Enjalbert’s view, the slow pace of progress with BRI projects is partly because of the complexity of such large-scale programs and the number of parties involved.

“Establishing new infrastructure projects is always a challenging undertaking that can be impacted by many different factors,” Enjalbert said. [Source]

At Reuters, Ben Blanchard and Robin Emmott report further on the ways that Beijing is attempting to ease mounting concerns over the BRI ahead of its second summit:

China has been on a push to show that the Belt and Road remains popular, despite cooling enthusiasm from governments including those of Sri Lanka, Malaysia and the Maldives, where new administrations are wary of deals struck with China by their predecessors.

The Chinese government’s top diplomat, State Councillor Wang Yi, who ranks below Yang, last month touted the success of the $57 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a major Belt and Road scheme.

[…] Wang told reporters at March’s annual meeting of parliament that the Belt and Road was about high quality, sustainable, green development.

“As President Xi has said, the Belt and Road initiative comes from China, but the achievements belong to the world,” Wang said. [Source]

The Wall Street Journal’s Chun Han Wong and Yantoultra Ngui report on a stalled BRI project in Malaysia that Beijing finally got signed by significantly slashing its price:

The two governments wrangled for months over the project, which critics had lambasted as overpriced. On Friday, Chinese and Malaysian executives in Beijing signed an agreement that cuts the cost of the East Coast Rail Link project to 44 billion ringgit ($10.7 billion) from 65.5 billion ringgit, according to a statement from the office of Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad.

Mr. Mahathir had suspended the project, along with other China-backed infrastructure deals, after winning election last spring on pledges to fight corruption and shore up Malaysia’s stretched finances. His gesture heaped pressure on Beijing as it sought to fend off mounting criticism of Mr. Xi’s Belt and Road initiative, which aims at expanding China’s trade links and strategic influence.

[…] Friday’s revised deal with Malaysia is timely for Mr. Xi as he prepares to host dozens of foreign leaders for a Beijing forum in late April to discuss Belt and Road cooperation. Chinese experts say it adds heft to Italy’s recent decision to formally support the initiative—the first such gesture from a major European power. [Source]