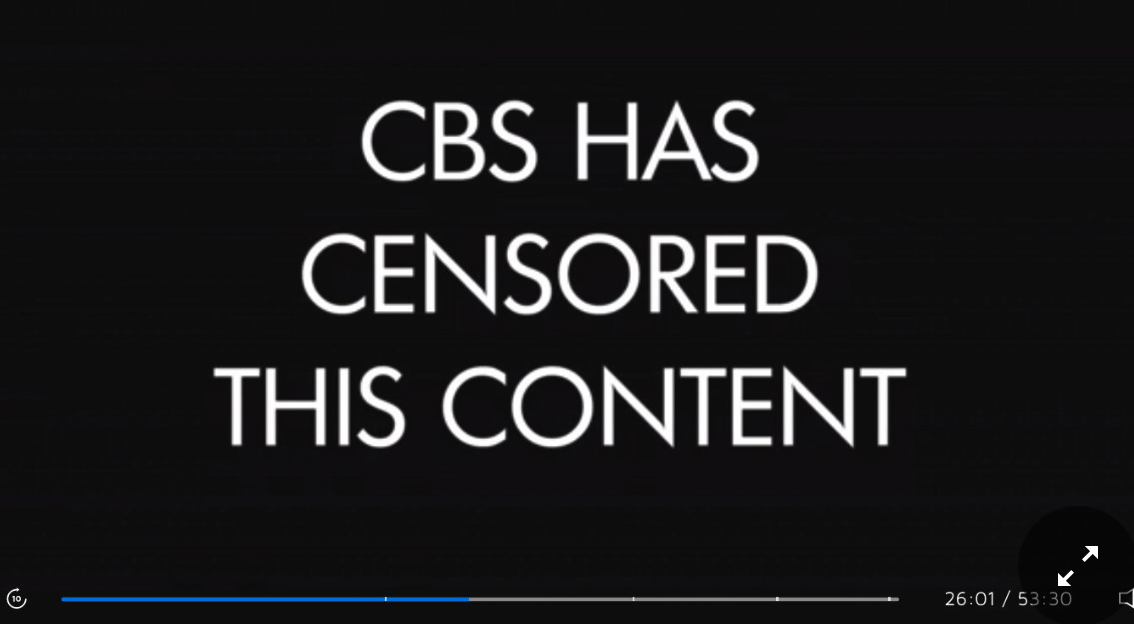

The CBS show “The Good Fight,” a spin-off of “The Good Wife,” recently removed an animated clip addressing censorship in China and replaced it with a slide stating that the content had been censored by CBS. Emily Nussbaum reports for The New Yorker:

[Jonathan] Coulton told me that the censored song is called “Banned in China.” (Full disclosure: Coulton is a friend of mine and recently paid me to appear as a guest on an extremely nerdy cruise-ship event.) It begins with a verse about the fact that “The Good Wife” itself had been banned in China, in 2014, possibly in reprisal for a Season 2 episode called “The Great Firewall,” which portrayed a Google-like company, called ChumHum, exposing a Chinese dissident to government torture. The next verse of the song is about the way that media companies censor content, with animations of movie scenes being snipped out of film strips.

Then comes the bridge, which lists other things banned in China, many of them symbolic images that Chinese citizens use on social-networking sites to evade censors. These include an empty chair (representing the late Chinese Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo), Winnie-the-Pooh (who is said to resemble China’s leader, Xi Jinping), and “the letter ‘N’ and Tiananmen Square”—a reference to the fact that the letter “N” was briefly banned in China, because it was perceived as a coded reference to the elimination of Presidential term limits. One animation showed the Chinese leader, dressed as Winnie-the-Pooh, shaking his bare bottom. Another showed Chinese reëducation camps.

The song is clear about one of the motives for American self-censorship: China is too big of a market for media corporations to ignore. Like the episode around it, the lyrics touch on the notion that Western culture might help spread democratic ideals, even under censored conditions—but it’s ultimately damning about how easily what might begin as a pragmatic compromise can become an excuse for greed. The clip ends with Coulton, in animated form, singing that he hopes his song gets banned in China—something that can’t happen now, given that it was preëmptively removed by CBS. [Source]

Julia Jacobs at The New York Times reports on CBS’ explanation of the removal:

Mr. Coulton said that he was told that CBS had concerns for the safety of its employees in China if the segment were included. CBS also has a Chinese audience, and when releasing content that is critical of China, American entertainment companies often have to weigh the risk of having their shows or movies blocked in the country.

Just before the censorship message, in fact, the show’s characters discuss a fictional tech company’s decision to appease Chinese censors. The company, called ChumHum, is engaged in a secret project to build a “customized” search engine for China. (Google was said last year to be considering such a product.)

“Customized? As in it allows China to censor its content?” one of the characters says.

A ChumHum executive responds: “We don’t like to call it censoring. It just obeys the laws of the land.” Seconds afterward, the show cut to its brief “censored” message. [Source]

Journalists who have worked in China expressed doubt over CBS’ concerns for employee safety in China:

Who was it at CBS who made this call? What kind of footprint does CBS have in China anyway? CBS News in China runs on a shoestring. Other news orgs with far bigger staffs in China regularly publish material that upsets Beijing. For CBS to think this is OK is troubling. https://t.co/jOmyg9o49J

— Mike Forsythe 傅才德 (@PekingMike) May 8, 2019

Most journalists who have run news bureaus in China would disagree with CBS on their assessment that broadcasting a segment on Chinese government censorship in a fictional show would endanger CBS News employees in China. https://t.co/5qRb62VBdT

— Edward Wong (@ewong) May 8, 2019

The show had previously been lauded by China watchers for a scene in the same episode in which a Uyghur activist discusses the detention of her family in internment camps.

China’s mass internment of Turkic minorities is a plot point in the CBS drama @theGoodFight, in which a woman testifies in court that her family has been sent to the “internment camps in Xinjiang.” Strikes me as important for a few reasons. A short thread… https://t.co/BNWCSaDXsY

— Rian Thum (@RianThum) May 4, 2019

https://twitter.com/BeijingPalmer/status/1125532031558070273

While Hollywood has long shied away from any film content directly critical of China for fear of alienating the country’s censors and market, such self-censorship is less common in American TV shows.

An uncensored political story line about Chinese malfeasance is on tap at @VeepHBO. https://t.co/7zxwnc1gUY

— Frank Rich (@frankrichny) May 8, 2019

If Beijing’s “red lines” on content grow to expand beyond traditional topics to include its influence ops, bribery, or elite capture — and there’s some evidence this is already happening — then the accountability and transparency democracy requires will be seriously damaged. 2/

— Rush Doshi (@RushDoshi) May 8, 2019

https://twitter.com/ChinaLawTransl8/status/1126169104942018560

2/? When corporate speech platforms (or airlines) self-censor for profit, they have accepted market access as their payment for the injury. The audience has no such remedy, but like the artists, should recognize that the station is complicit in the censorship.

— China Law Translate (@ChinaLawTransl8) May 8, 2019

3/ The company has decided that the censoring market is more easily lost, or more important, than the domestic one. Audiences outside of China might let CBS know that they object to losing their right to view the artists' work, and that they can weaponize dollars too.

— China Law Translate (@ChinaLawTransl8) May 8, 2019

Read about Head Gear Animation, the Toronto-based studio that produced the censored “Good Fight” clip via the Globe and Mail. Read more about Hollywood’s increasingly interdependent relationship with China in a CDT Q&A with UCLA professor Michael Berry.