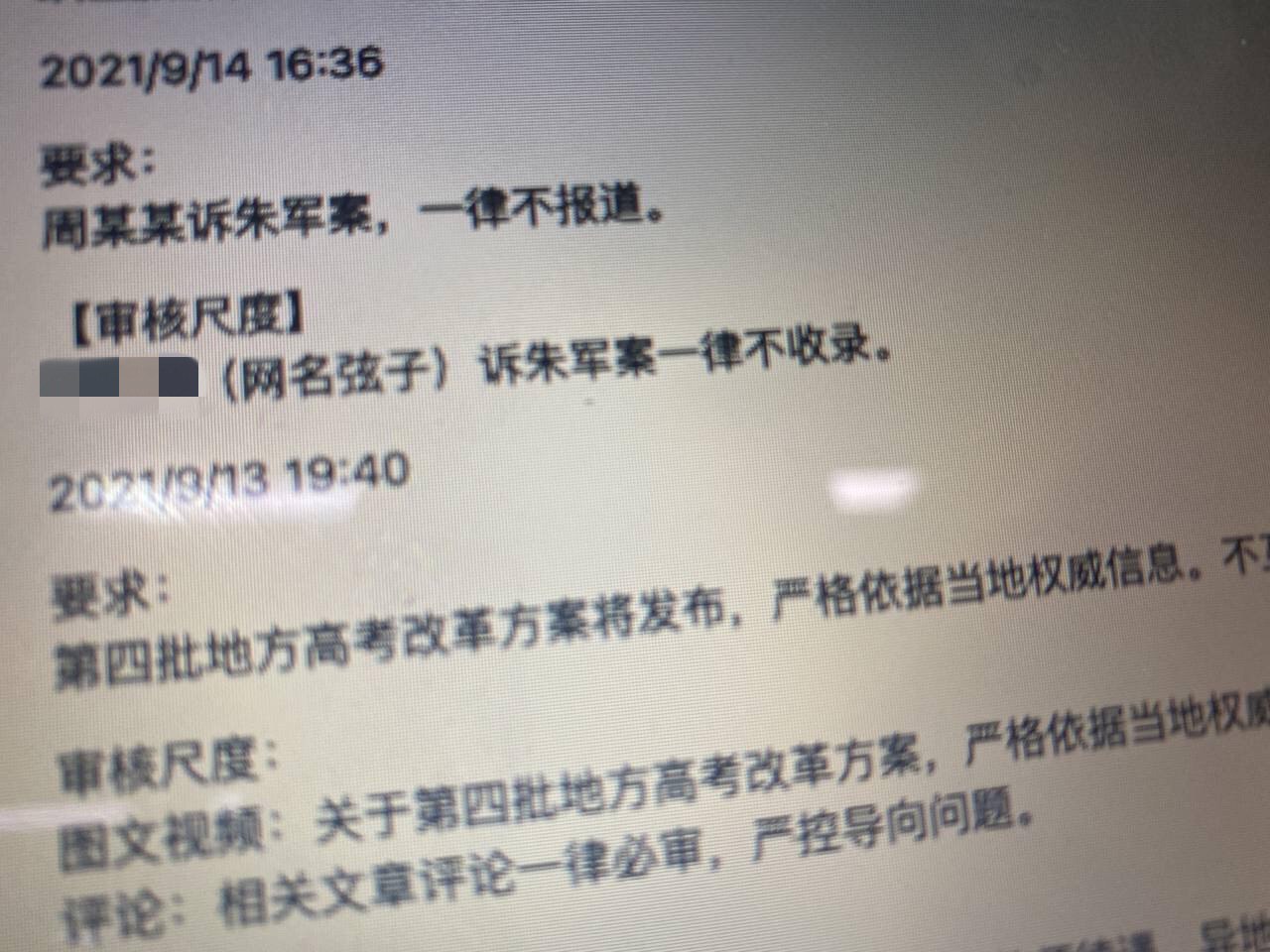

The following censorship instructions, issued to the media and internet companies by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

2021/9/14 16:36

Directive: Do not report on Zhou _ _’s lawsuit against Zhu Jun, no exceptions.

Censorship Standards: Do not include any content on Zhou _ _’s (screen name Xianzi) lawsuit against Zhu Jun, no exceptions.

2021/9/13 19:40

Directive: Regarding the upcoming release of the fourth round of reform plans for provincial university entrance examinations, strictly adhere to authoritative local sources of information. Do not… [missing text]

Censorship standards for video and graphics: Regarding the upcoming release of the fourth round of reform plans for provincial university entrance examinations, strictly adhere to authoritative… [missing text]

Censorship standards for comments: All comments on related articles must be reviewed, and the direction of the commentary must be strictly controlled. (September 13-14, 2021) [Chinese]

CDT Chinese editors note that this screenshot cannot be verified. In 2018, Zhou Xiaoxuan—a screenwriter who goes by the nickname Xianzi (弦子)—posted an article on Weibo describing how celebrity television host Zhu Jun assaulted her in his dressing room in 2014, when she was a 25-year-old intern working at CCTV. The article went viral, galvanizing China’s #MeToo movement and inciting intimidation and threats against Xianzi and her parents. In response, Zhu Jun filed a defamation lawsuit against Xianzi and a friend of hers, seeking compensation of 650,000 yuan ($100,000) for damage to his reputation. Xianzi counter-sued for sexual harassment under China’s new Civil Code, seeking a public apology and 50,000 yuan ($7,700) in damages. The lawsuit wound its way through Beijing’s Haidian District Court for three years, during which time the court consistently refused to admit Xianzi’s 2014 police report, DNA evidence, surveillance footage, and other evidence that would help to prove her case. A closed ten-hour hearing in December 2020 was inconclusive, and a second hearing on May 21, 2021 was abruptly postponed. On September 14, 2021, Xianzi’s case was dismissed for “lack of evidence,” although she has vowed to appeal.

Over the last three years, social media platforms such as Weibo and Douban have been actively censoring discussion of the case, and have been quick to suspend or permanently close accounts of users who post about it. Xianzi’s personal Weibo account was banned during a mass purge of LGTBQ+ and #MeToo Weibo accounts earlier this year. This latest court decision has triggered yet another round of censorship and social media account closures. Accounts that used the hashtag #speakingoutforthesilenced were shut down completely, while those that used the hashtag #wedemandanswersfromhistory (the slogan supporters brandished on placards outside the first hearing) were hit with suspensions of one or two weeks. One Douban user created a partial list of victimized accounts and asked that it be shared widely, in protest against Weibo’s censorship: “Today is not only the second hearing in Xianzi’s lawsuit against Zhu Jun, but also the day that our innumerable sisters were ‘murdered’ on Weibo for supporting Xianzi and speaking out on her behalf.” Protocol’s Shen Lu reported on the deletions:

The Tuesday trial was closed to outside observers, and tech companies like Weibo are now actively blocking public discussions of the court ruling. Shortly after the trial, Weibo users (including this author) started receiving messages from platform administrators that notified them of account suspensions due to recent posts that “violated relevant national laws and regulations,” which is the language most frequently used to identify politically disfavored online speech. The suspension windows range between seven days and 30 days. During their suspensions, users cannot comment or share. Some users with large followings even saw their accounts deleted for good.

[…] The censorship initiative went wide and deep. One Weibo user wrote in a post that at least 20 of their Weibo friends who shared posts about the Tuesday trial had been muzzled; they had only a few dozen friends on Weibo.

“Today’s Weibo looks like a graveyard,” one user posted on Tuesday, adding their feed was “full of posts about friends whose accounts were suspended, deleted or who are ‘reborn’ with new accounts.” [Source]

The other instructions captured in the screenshot relate to the fourth round of regional national college entrance examination reforms announced by the Ministry of Education on September 16. The exam, commonly known as the gaokao, underwent the first round of reform in 2014. Second and third rounds of reforms followed in 2017 and 2019, respectively. The fourth and most recent round of reforms applies to seven provinces: Heilongjiang, Jilin, Gansu, Anhui, Jiangxi, Guizhou, and Guangxi. The reforms vary from province to province, and include scoring changes, the cancellation of separate tests for liberal arts and hard sciences, and the adoption of the “3+1+2” model: all students are tested on the three mandatory subjects of Chinese, mathematics, and a foreign language, plus additional selections from a range of elective supplementary tests. Changes to the all-important exam can be controversial: in 2016, thousands of parents from three provinces took to the streets to protest reforms.

Joseph Brouwer contributed to this post.