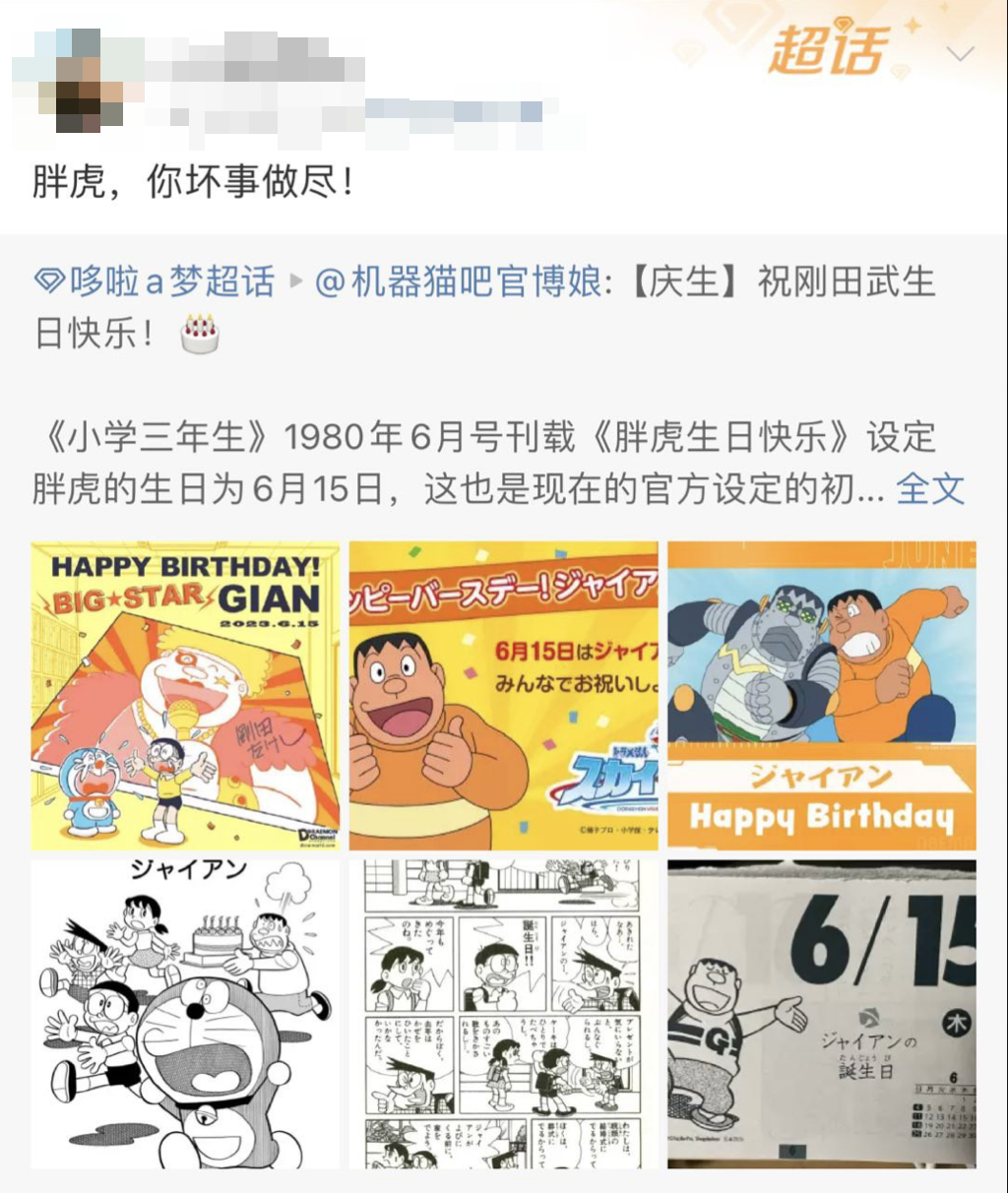

Today, June 15, is Xi Jinping’s 70th birthday. The birthday itself is a taboo topic on Weibo. Commentary has been restricted to state-affiliated accounts, all of which relay identical pablum about well-wishes from friendly heads of state: Russia’s Putin, North Korea’s Kim, and Kazakhstan’s Tokayev. As such, netizens wishing to discuss Xi’s big day have been forced to find a workaround. They’ve found one in a character from the wildly popular manga and anime series “Doraemon”: Takeshi Gouda, better known as “Big G” (or 胖虎 Pàng Hǔ in Chinese), canonically celebrates his birthday on June 15. The comparisons between Big G and Xi do not end there. Baidu Baike, a Chinese Wikipedia knockoff, describes Big G as a bully with crude manners, an elementary school education, and a passion for soccer. Xi’s detractors cannot help but see the similarities. The use of Big G as a stand-in for Xi Jinping first started in 2020. Now, Weibo seems to be censoring comments about “Big G’s birthday,” apparently attuned to the subversive subculture that has grown up around the beloved Doraemon character. It seems that “Big G” may have been added to the list of 546 forbidden derogatory nicknames for Xi.

Birthdays are not major events in the Communist Party’s calendar, at least not officially. (In the late 1970s, while still out of power, Deng Xiaoping reportedly used an octogenarian’s birthday party to flaunt his continued influence within the People’s Liberation Army.) At The Wall Street Journal, Austin Ramzy and Chun Han Wong reported on the Party’s low-key birthday traditions, a precedent set by Mao Zedong:

[Xi] is also relatively young by the standards of Chinese leaders. Mao Zedong held power until his death in 1976 at the age of 82. Deng Xiaoping stepped down as chairman of the party’s Central Military Commission in 1989, but continued to wield power behind the scenes without any party leadership posts until his death in 1997 at the age of 92.

The state of Xi’s health is a closely guarded secret, though politically minded Chinese and foreign analysts have traded gossip about his physical well-being from time to time. Xi has taken to giving major, lengthy speeches at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People seated, as opposed to earlier in his rule, when he generally delivered such addresses standing.

[…] Xi’s clout is often compared with that of Mao, who imposed restrictions on the celebrations of Chinese leaders’ birthdays, saying they risked promoting arrogance. “We must keep to our style of plain living and hard work and put a stop to flattery and exaggerated praise,” he said in March 1949.

The rule remained largely in place even as the cult of personality around Mao grew during the Cultural Revolution. On Dec. 26, 1973, when Mao turned 80, the People’s Daily carried a story about a model worker in his hometown of Shaoshan in Hunan province, but didn’t mention the significance of the date, the New York Times reported at the time. [Source]

While the Party does not officially put stock in birthdays, those courting Xi do, especially Putin. At The New York Times, Chris Buckley and Paul Sonne reported on Putin’s efforts to ingratiate himself with Xi through birthdays, and thus secure Russia a powerful partner:

Mr. Putin sent Mr. Xi a congratulatory telegram when the Chinese leader turned 70 on Thursday, wishing his “dear friend” good health, happiness and success, further cementing the image of a personal bond between the two authoritarian leaders.

“It is difficult to overestimate the effort that you have made over many years to strengthen our comprehensive partnership and the strategic interaction between our countries,” Mr. Putin wrote.

[…] Mr. Xi, in particular, appears determined to keep treating Mr. Putin as an esteemed peer, united by a shared conviction that the United States and its allies want to drastically weaken Russia and stymie China’s rise as a great power. The two leaders reaffirmed their countries’ partnership at a summit in Moscow in March. And they have used birthdays to signal their closeness since Mr. Xi became China’s leader in 2012, trading gifts including ice cream, an embroidered portrait of Mr. Putin, and a Russian “YotaPhone” for Mr. Xi.Yu Bin, an expert on Chinese-Russian relations who is a senior fellow at East China Normal University in Shanghai, nonetheless cautioned against reading too much into the shows of bonhomie. “There is a personal touch, but I would not exaggerate that,” he said. “First and foremost, the pursuit of a normal relationship between the two large countries is paramount.” [Source]