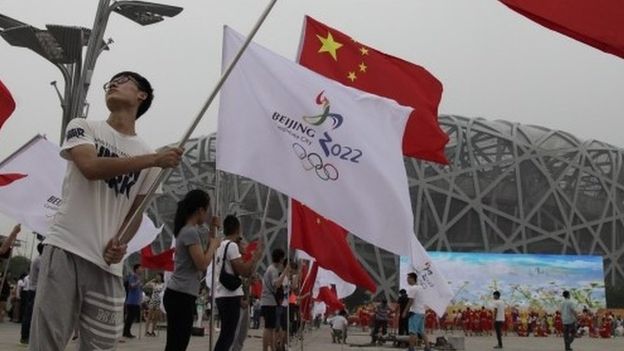

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) this morning announced that China won its $1.5 billion bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics, beating out Kazakhstan on a surprisingly narrow ballot. The AP reports that Beijing will become the first city to host both winter and summer games in the history of the Olympics, notes a voting mishap that roused some suspicion, and relays discontent from Kazakh representatives:

The Chinese capital was awarded the 2022 Winter Olympics on Friday, beating Kazakh rival Almaty 44-40 in a surprisingly close vote marred by technical problems, taking the games back to the city that hosted the summer version in 2008.

Beijing was seen by the International Olympic Committee as a secure, reliable choice that also offered vast commercial opportunities in a new winter sports market of more than 300 million people in northern China.

“It really is a safe choice,” IOC President Thomas Bach said. “We know China will deliver on its promises.”

The IOC’s secret vote was conducted by paper ballot, after the first electronic vote experienced technical faults with the voting tablets and was not counted. The result of the first vote was not disclosed. There was one abstention in the paper ballot.

Bach bristled when asked at a news conference about the possibility of any voting irregularities. […] [Source]

Bach’s stated confidence is based on Beijing’s proven ability to finance, prepare infrastructure, and host the 2008 Summer Olympics. While some of the infrastructure from 2008 will be dusted off and revamped for 2022, there are worries that the site selected for snow events may prove to be problematic. The Economist describes the arid and far-flung city of Zhangjiakou, and greater environmental concerns over a burgeoning Chinese ski industry:

[…W]orrying is China’s ambition to stage the winter Olympics—and launch a winter sports industry—in an arid desert (Zhangjiakou is near the Gobi). Almost every winter Olympics venue uses artificial snow to supplement their own supply, and to ensure a plentiful supply of the best kind. But most have far more of their own to start with. Although China does have areas which are covered in the real stuff through the winter, but these lay further away from the capital, to the far north and northeast.

The government has already quashed the growth of golf, another sport whose high water demands were deeded excessive. But it now plans to spend nearly $90m on water-diversion schemes to satisfy Olympic demand. The country has already invested in giant diversion schemes to channel water hundreds of miles from the south to quench the thirst of the capital; groundwater supplies are being used up too.

Of greater concern to environmentalists than a two-week party in 2022 is the broader attempt to launch China’s own domestic ski industry. The sport is still very much in its infancy: on an average winter weekend most of the skiiers sliding down the fake snow at Zhangjiakou are beginners. It is also too expensive for most Chinese. Yet for months airports around the country, including in the balmy south, have been attempting to flog winter sports to Chinese consumers. It may also now persuade a few of them to practice rather hard. China not only needs to make some snow, it needs to make some gold-medal winners too. [Source]

Winter sport related environmental concerns may proliferate in years to come. At The New Yorker, Christopher Beam reports on efforts to promote winter sports in China, where they are currently unaffordable and lack traditional popularity:

The problem is that, despite some evidence that skiing may have originated in the Altai Mountains of Xinjiang province, China does not have a strong tradition of winter sports. South of the Huai River, which runs through the middle of the country, temperatures generally stay above freezing. Even Zhangjiakou, where many of the events will be hosted in 2022, sees only about three feet of snow every year. (The campaign for Almaty, Kazakhstan, Beijing’s rival for the Olympic bid, promised “real snow, real winter ambience.”) On a February day in Beijing, you’ll see more people walking on frozen lakes than skating. China’s performance at the Winter Olympics has improved since the nineteen-eighties, when it failed to win a single medal, but it doesn’t come close to matching its recent summertime dominance. The country won nine medals at the 2014 Games in Sochi, six of them in short-track speed skating, a relatively new Olympic sport at which China excels.

Winter sports are also a fancy form of recreation in China. To skate at the Ice and Joy rink in Chengdu costs seventy yuan, or twelve dollars, and a package of ten hockey or skating lessons costs about four hundred and sixty-four dollars. Playing on a hockey team drives the expense higher, with families typically spending as much as ten thousand dollars on equipment, travel, and fees. (The average Chinese person has an annual disposable income of about three thousand two hundred and fifty dollars.) One father I spoke with, Chen Cheng, estimated that he spends more than forty-eight thousand dollars a year on his eight-year-old son’s hockey career, including flights to Beijing every weekend to play in a more advanced league. […]

[…] To prove his commitment to winter sports, President Xi Jinping has done everything short of strapping himself into a snowboard and hitting the halfpipe. […] [Source]

The 2008 games led to several human rights controversies: Beijing was criticized for its failure to live up to promises on media censorship, designated protest zones, and the loosening of Internet restriction; and for arresting prominent activists ahead of the games. Similarly, Moscow garnered criticism for it its rights records during last year’s winter games in Sochi. While the IOC’s Olympic Charter has sworn a commitment to “placing sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity” since 1991, it doubled down last December, amending the Charter and including several recommendations aimed directly at the protection of human rights in its “Olympic Agenda 2020.” Ahead of yesterday’s IOC vote and amid an intensifying government crackdown on civil society and free expression in China, prominent Chinese rights activists petitioned and international advocacy groups spoke out against Beijing’s bid; following the bid’s success, those concerns now echo. The AP reports:

“The IOC has sent the wrong message to the wrong people at the wrong time,” the International Tibet Network said in a statement. “China wants the world to ignore its deteriorating human rights and be impressed by Chinese can-do pragmatism instead. That’s exactly what the IOC has done. The honor of a second Olympic Games is a propaganda gift to China when what it needs is a slap in the face.”

[…] From New York, Human Rights Watch, which had also complained about human rights abuses by both Beijing and Kazakhstan ahead of the vote, said the IOC had “tripped on a major human rights hurdle.”

“The Olympic motto of ‘higher, faster, and stronger’ is a perfect description of the Chinese government’s assault on civil society: more peaceful activists detained in record time, subject to far harsher treatment,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch.

[…] In Hong Kong, city legislator Albert Ho, a lawyer and founding member of Hong Kong-based China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, said the decision suggested “the IOC has lost the spirit of the Olympics.” […] [Source]

In a report detailing close surveillance while visiting a ski resort slated to host games in 2022, John Sudworth notes that a Chinese representative relied on a common tactic when questioned by the BBC on human rights concerns—emphasize the right to economic development:

For Beijing the games would bring real development opportunities not just to resorts like Chongli, but to the wider province of Hubei that has always lagged behind the country’s capital.

[…] In fact, when asked about the other major area of concern surrounding Beijing’s bid – the issue of human rights – it is telling that the senior official put up to speak to the BBC begins her answer in terms of the economic and lifestyle benefits the games will bring.

“On the subject of human rights,” Wang Hui, the Bid Committee deputy secretary says, “the Winter Olympics are exactly meeting people’s needs.” [Source]

It should be noted that Almaty, Kazakhstan, Beijing’s only competitor in the final bid, scores only slightly higher on its human rights record. An essay from Victor Matheson at the Washington Post suggests that a possible trend towards autocratic Olympic bidders could be related to the massive price tag of preparation:

[…] If rich cities with well-developed infrastructure like London and Boston can’t host the Olympics without breaking the bank, how can any place keep costs down?

The answer, it’s becoming clear, is that they can’t. Which is why the voters in rich, industrialized cities are exercising the right to say no to the Olympics. There is no shortage of autocratic rulers, though, who might be willing to spend the money they have squeezed from their people in order to experience the ego-boost of hosting the world’s biggest sporting event in their own back yard. Pyongyang 2028, anyone? [Source]