After making history at the beginning of this month by becoming the first Asian woman to win best director for her movie “Nomadland,” Chloé Zhao was initially showered with praise from Chinese state media. That was until last week, when Chinese netizens dug up two interviews featuring Zhao, including one which erroneously quoted her as saying “The U.S. is now my country, ultimately.” A torrent of online criticism followed, and censors responded last week by wiping references to “Nomadland” from social media, seemingly banning the movie in China.

But Zhao was not the only film star to recently face the consternation of Chinese netizens. Netizens also expressed outrage at news that the ashes of recently-deceased comedy film star Ng Man-tat (of “Shaolin Soccer” and “All For the Winner” fame) would be flown to Malaysia to be closer to his family. The two incidents have highlighted the ferocity of nationalist sentiment on Chinese social media, prompting criticism and ridicule from others who see their anger as having gone too far.

For The New York Times, Amy Qin and Amy Chang Chien reported on the backlash against Chloé Zhao:

[…] Chinese online sleuths dug up a 2013 interview with an American film magazine in which Ms. Zhao criticized her native country, calling it a place “where there are lies everywhere.” And they zeroed in on another, more recent interview with an Australian website in which Ms. Zhao, who received much of her education in the United States and now lives there, was quoted as saying: “The U.S. is now my country, ultimately.”

The Australian site later added a note saying that it had misquoted Ms. Zhao, and that she had actually said “not my country.” But the damage was done.

[…] On Friday, censors barged in. Searches in Chinese for the hashtags “#Nomadland” and “#NomadlandReleaseDate” were suddenly blocked on Weibo, a popular social media platform, and Chinese-language promotional material vanished as well. References to the film’s scheduled April 23 release in China were removed from prominent movie websites. [Source]

Western observers were quick to note the irony of the ban on “Nomadland,” a drama about one woman’s itinerant life in the United States that highlights the precarity of blue collar work in the American gig economy–a message that, from one perspective, could be a boost for Chinese propagandists. Other observers have theorized that the “soft” ban on “Nomadland” may actually be a protective move to cool down the heated emotions towards Zhao.

As to Zhao, my hunch is there's an equilibrium that needs to be reached—between her potential controversy in China and her profile as a recognized director of Chinese descent. If Nomadland is really banned for now, it's likely an Oscar will change it

— Tony Lin 林東尼 (@tony_zy) March 5, 2021

Less reported in English media is the controversy surrounding the remains of recently deceased actor Ng Man-tat. Ng, also known as Wu Mengda, passed away at the end of February. He had spent much of his acting career based in Hong Kong, including during the city’s cinematic “golden age.” Beloved both in Hong Kong and mainland China, he earned the nickname “Uncle Tat” for his recurring sidekick role playing an uncle to actor-director Stephen Chow, including in several hugely popular slapstick comedies such as “All for the Winner” and “Shaolin Soccer.”

But thanks to Ng’s popularity in mainland China, news that his cremated ashes would be transported to Malaysia, where his wife and children reside, drew an outcry from nationalist netizens. Other commentators saw the outrage as a step too far. CDT translated a post on WeChat which humorously lambasted “patriotic fools”:

Uncle Tat Is Not Allowed to Die Outside

By 六神磊磊、秦山

After acting foolish his entire life, Uncle Tat would surely feel a little bit foolish right now if he could hear from the grave.

This is actually true—after a collective few seconds of scrutinizing Stephen Chow’s presence at Tat’s funeral, many netizens unrelentingly called into question the next issue: why should Ng Man-tat’s ashes be brought back to Malaysia?

According to news reports, after Uncle Tat died, his ashes were taken to Malaysia. This was at Uncle Tat’s own request, because his wife and children live there, and he wanted to “accompany his wife and children.” Uncle Tat’s younger brother Ng Lee-tat confirmed this when interviewed.

But this arrangement caused much dissatisfaction among netizens. They loved Uncle Tat too much, and were heartbroken: “Uncle Tat belongs to China!”

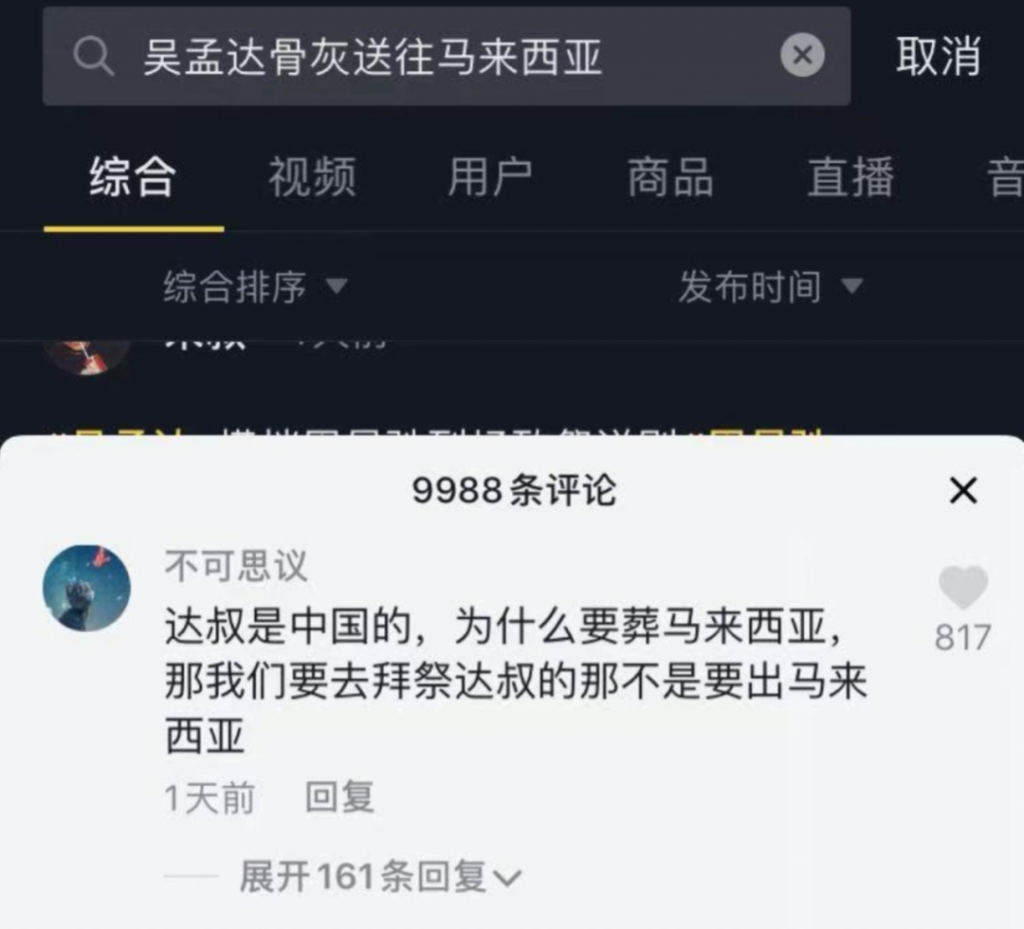

For example, this comment: “Uncle Tat belongs to China, why bury him in Malaysia? If we want to pay respects to Uncle Tat, won’t we have to go to Malaysia?”

They received 800 likes:

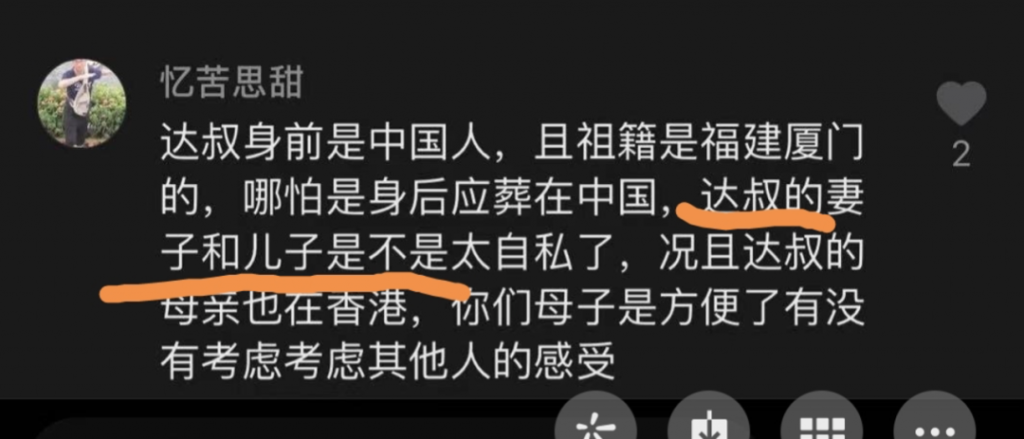

They even said that Uncle Tat’s family was “too selfish.”

One person said: “Uncle Tat was Chinese when he was alive… so when he’s dead he should be buried in China. Aren’t Uncle Tat’s wife and son being too selfish? … Have they even considered how other people might feel?”

[…] Some were stunned after seeing the above comments. They said celebrities are the only ones with an iron rice bowl: from cradle to grave, you’re taken care of by netizens; even your ashes are properly arranged for you.

These people, they manage everything so well except their own affairs. There have no sense of boundaries, of scale, or of reality, only a dominating sense of moral righteousness.

Uncle Tat is Chinese, they are also Chinese, therefore they feel they have the right to manage his ashes. Patriotism was originally a pretty good thing, but some people have become patriotic fools, causing others to be embarrassed to love their country.

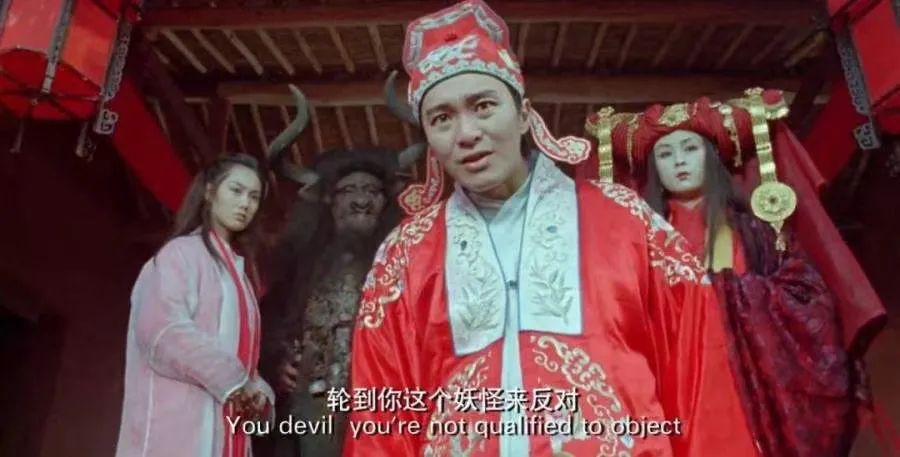

[…] To borrow a line from “A Chinese Odyssey,” wherever Ng Man-tat’s ashes are placed, “you devil, you’re not qualified to object.” If Uncle Tat’s wife and child don’t make it easy for themselves, who should they make it easy for? For you?

If other people’s ashes don’t accompany their families, should they accompany you?

Let’s put them in your house, why don’t we?

(Image from “A Chinese Odyssey“)

[Chinese]