At The South China Morning Post, Dinah Gardiner talks to writers and publishers—including Evan Osnos, Peter Hessler, Ezra Vogel, and Perry Link—who have had to make the choice between appeasing Chinese censors or refusing to publish in the mainland:

[…] Peter Hessler, Osnos’ predecessor at The New Yorker, argues that writers bear a moral responsibility to be accountable to the people they are writing about, which must be weighed against the cost of censorship.

“An absolutist stand can be a way of disengaging or not thinking hard about a situation,” he says. “It’s an unhealthy dynamic that is common all over the developing world – the foreign correspondent often feels like he’s exporting stories. He doesn’t receive local feedback and there’s a risk that he isn’t fully accountable to his subjects.”

Hessler has published two books in the mainland – Country Driving and River Town. The cuts inflicted “did not strike at the core” of either book, he says: Country Driving came out minus 4½ of its more than 400 original pages and River Town fared slightly better, having two pages shaved off out of more than 440. Since Hessler tends to focus on local communities rather than political leaders (such as Vogel’s Deng Xiaoping) or dissidents (like Osnos’ Age of Ambition) his work is much less sensitive. Publishing was “a compromise, and one that doesn’t make me completely happy, but I believe it’s worth it”, says Hessler.

He didn’t bother looking for a Chinese publisher for his third book, however. In part, Oracle Bones follows the fate of Polat, a Uygur man strongly critical of the government. Hessler knew the censors would have had a field day. “It would be an insult to Polat if I gave the Party control over his story.” […] [Source]

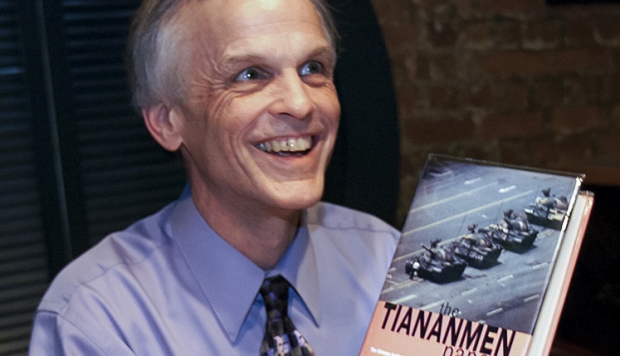

Also see Evan Osnos’ explanation of why he chose not to publish his recent book in China, or coverage of Harvard professor Ezra Vogel’s controversial acceptance of censorship for the mainland publication of his book on Deng Xiaoping, both via CDT.