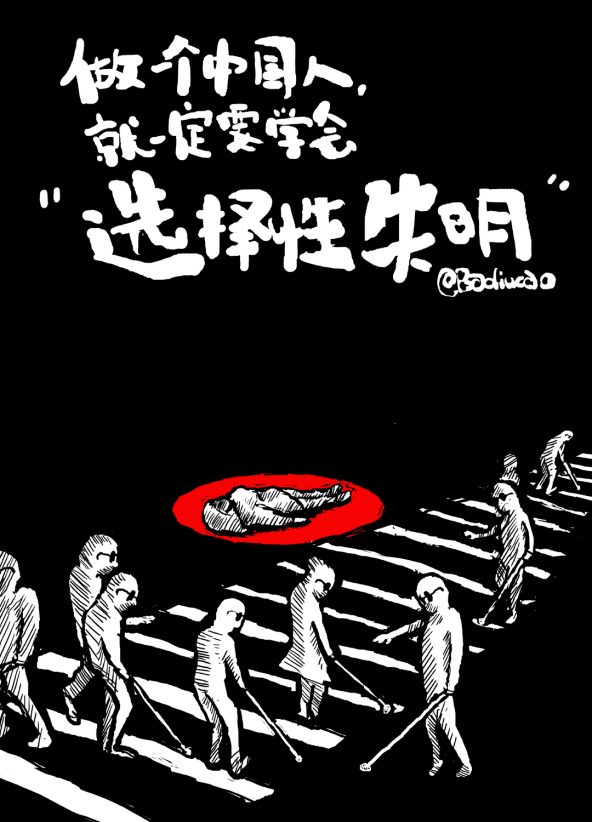

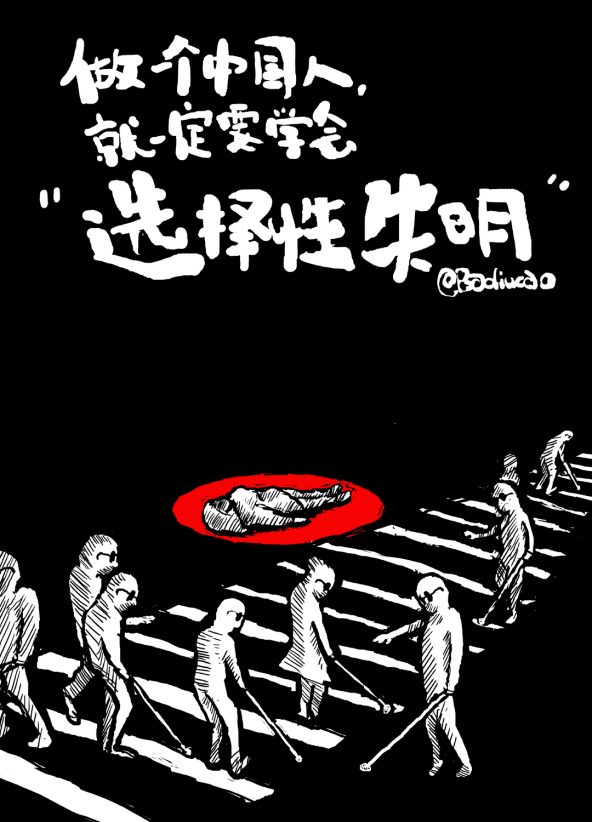

CDT cartoonist Badiucao comments on a recent viral video in which a woman was hit by a vehicle while crossing the road in Zhumadian, Henan, and left unaided until a second vehicle killed her. The clip drew millions of views and tens of thousands of shares and comments, rekindling widespread soul-searching about the state of public morality in China. “To be Chinese,” Badiucao writes, “one must cultivate a ‘selective blindness.'”

The drivers of the two vehicles are reportedly in custody. At least one copy of the video has been “removed for violating YouTube’s policy on violent or graphic content,” but others remain online with graphic content warnings and age confirmation requirements.

The incident has prompted comparisons with the similar case of a Guangdong toddler who died after being run over twice, to the apparent indifference of passers-by, in 2011. One popular explanation is the risk of becoming a “good Samaritan” in China, following a series of episodes in which helping a stranger led to blame for their injuries. (Further muddying the water, the “good Samaritan” in one prominent case later turned out to have been guilty.) Several local laws have been introduced to address the problem, with nationwide protections promised as part of China’s new civil code.

But many Chinese see these incidents and the risk of unfair legal liability as symptoms of a broader and more profound problem. According to the Associated Press’ Gerry Shih, many of those commenting online viewed the video as a “94-second reminder of their society’s deep rot“:

Here, the common refrain goes, is an unmoored country where manufacturers knowingly sell toxic baby formula and fraudulent children’s vaccines. Restaurants cook with recycled “gutter oil” and grocery stores peddle fake eggs, fake fruit, even fake rice. Many Chinese say they avoid helping people on the street because of widespread stories about extortionists who seek help from passers-by and then feign injuries and demand compensation — perhaps explaining the Zhumadian behavior.

[…] The news swept through social media and even state media outlets. The Communist Youth League, an influential party organization, circulated the video on its Weibo account, urging its 5 million followers to “reject indifference.” An opinion column on china.com, a state media organ, asked citizens to “reflect” on the tragedy. Others used the episode as a starting point to vent about social ills.

[… Tian You, a novelist based in the southeastern city of Shenzhen,] cited the Cultural Revolution unleashed by Mao Zedong in the 1960s, which turned families and neighbors against each other in a battle for survival. Hyper-capitalistic, no-holds-barred competition consumed the reform era that followed Mao’s death.

“Our political system doesn’t regulate the things it should and it manages things it shouldn’t,” said Zhang Wen, a well-known Beijing commentator who pointed out that many charitable organizations have disbanded due to government pressure, resulting in a decline of “charity spirit.” [Source]

The New York Times’ Ian Johnson also examined the debate, including moral, legal, and political arguments:

Since coming to power in 2012, President Xi Jinping has made public morality a top priority. In addition to a better-known anticorruption campaign, the government has introduced a campaign to promote values, many of them traditional.

Some online commentators, however, said those efforts had not yet borne fruit.

“There is a lack of citizenship in society,” said Qiao Mu, an independent scholar in Beijing. “People feel society is too cold.”

[Zhang Xuebing, a lawyer and a former law professor at the East China University of Political Science and Law in Shanghai,] said that government policies are partly to blame. Although the government preaches morality, its actions often undermine that message.

“You need to pay attention to what our government has been doing,” Mr. Zhang said. “Our government sentences a father whose son gets kidney stones after drinking toxic milk powder for petitioning. It also demolishes the libraries set up by nonprofits in the countryside to help poor kids who don’t have a proper education.” [Source]

On his personal blog, the University of Nottingham’s Jonathan Sullivan wrote—emphasizing that “no one should interpret either incident as reflecting the inhumanity or wickedness of ‘the Chinese people'”—that the phenomenon appears to extend beyond a simple lack of interpersonal trust to a broader and deeper sense of anxiety:

[… I]f the prevailing explanation for why a woman and toddler were left to die in the street unaided is a lack of trust, then that should prompt consideration of how Chinese society got to this point. This discussion is going on in Chinese cyberspace right now, and there is excellent scholarly work too (e.g. here and here). There is much debate about what effects trust levels in China (from the political system to culture to historical legacies). In sum, we can probably say that it is not mono-causal and therefore any “solution” will also need to be multifaceted.

The lack of trust is pervasive and manifest in a multitude of mundane and potentially grave experiences. Can you trust that crossing the road on your green light a car won’t run you over? Can you trust that the milk powder or soy sauce you buy isn’t poisonous? Can you trust that the risque joke you made on Weibo today won’t come back to haunt you tomorrow? Can you trust that the soil or air in your town isn’t slowly killing you? Can you trust that the people you do business with will honour the contract? And so on.

One could choose any number of alternative examples invoking any number of different issues and sectors. The point is that there is no single solution to a condition that manifests itself in myriad ways in billions of quotidian interactions, from the top of society to the bottom, and which sometimes results in a woman dying under the gaze of passersby. [Source]

Fears that the Chinese people’s safety and prosperity are more precariously balanced than they seem have previously been agitated by incidents such as the 2015 Tianjin explosions and fatal beating of university graduate Lei Yang by police last year, while the plight of the country’s “left-behind” children has stirred anxieties about its moral direction.