New reports, based on interviews with former detainees and data collected from official sources, have provided previously unknown details about the extent of mass re-education camps in Xinjiang. While the government has denied the existence of such camps, reports have estimated that between tens of thousands and a million people have been detained in them in recent years. Drawing on official recruitment notices, government procurement and construction bids, and local budget reports, Adrian Zenz of the European School of Culture and Theology has written a lengthy report proving the existence of such camps, which are predominately used to house and “reeducate” Muslim residents, including Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz. From a summary of his report published by the Jamestown Foundation (the full report can be read via academia.edu):

It was not until 2014 that the “transformation through education” concept in Xinjiang came to be systematically used in wider contexts than the Falun Gong, Party discipline or drug addict rehabilitation. Its application to Uyghur or Muslim population groups arose in tandem with the “de-extremification” (去极端化) campaigns, a phrase first mentioned by Xinjiang’s former Party secretary Zhang Chunxian in 2012 (Phoenix Information, October 12, 2015).

In 2014, the re-education system started to evolve into a network of dedicated facilities. Konashahar (Shufu) County (Kashgar Prefecture) established a three-tiered “transformation through education base” (教育转化基地) system as part of its “de-extremification” efforts (Xinjiang Daily, November 18, 2014). It operated at county, township and village levels. A three-tiered re-education system based on these three levels is likewise mentioned in a 2017 government research paper described below, one whose ideas have apparently found widespread adoption (Harmonious Society Journal via www.doc88.com, p.76, June 2017).

[…] The start of Chen Quanguo’s re-education initiative correlates closely with the release of detailed information in the form of government procurement and construction bids (采购项目 and 建设项目). Nearly all bids were announced from March 2017, just prior to the re-education drive (Figure 1, based on Table 1). Likewise, the values attached to these bids were by far highest in the months immediately after the start of the re-education campaign (Figure 2). While only a fraction of re-education facility construction is reflected in these bids, they do indicate a pattern consistent with re-education policy and implementation.

[…] While there is no published data on re-education detainee numbers, information from various sources permit us to estimate internment figures at anywhere between several hundred thousand and just over one million. The latter figure is based on a leaked document from within the region’s public security agencies, and, when extrapolated to all of Xinjiang, could indicate a detention rate of up to 11.5 percent of the region’s adult Uyghur and Kazakh population (Newsweek Japan, March 13). The lower estimate seems a reasonably conservative figure based on correlating informant statements, Western media pieces and the comprehensive material presented in the long version of this article. It is therefore possible that Xinjiang’s present re-education system exceeds the size of the entire former Chinese re-education through labor system. [Source]

Gerry Shih of AP reported from Kazakhstan to interview former detainees of the Chinese system, some of whom were living in Kazakhstan but detained after crossing over into China. One such detainee, Omir Bekali, was a Chinese-born Kazakh citizen who returned to China to visit family when he was detained, tortured, and held incommunicado before being sent to a political indoctrination camp following a visit from Kazakh officials. From Shih’s report:

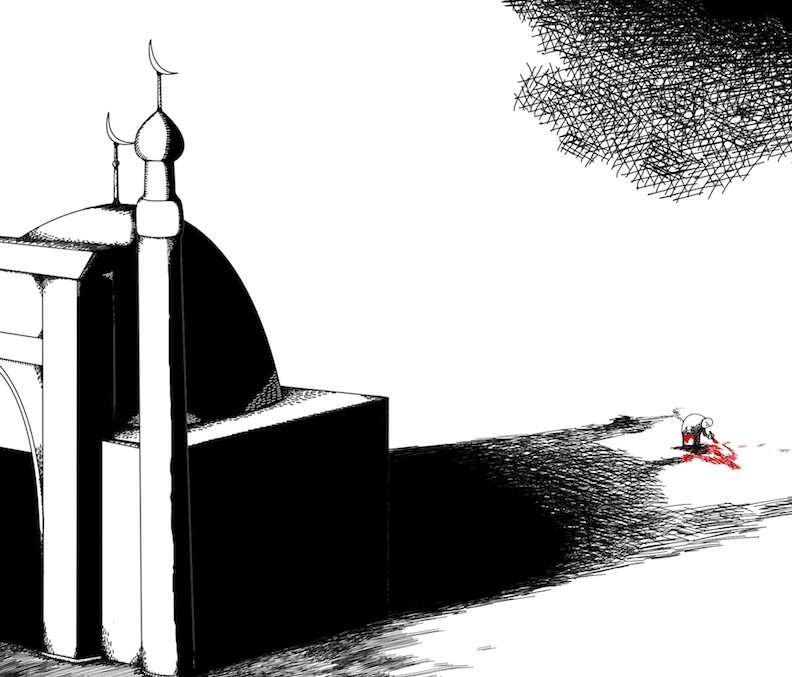

Chinese officials have largely avoided comment on the camps, but some are quoted in state media as saying that ideological changes are needed to fight separatism and Islamic extremism. Radical Muslim Uighurs have killed hundreds in recent years, and China considers the region a threat to peace in a country where the majority is Han Chinese.

The internment program aims to rewire the political thinking of detainees, erase their Islamic beliefs and reshape their very identities. The camps have expanded rapidly over the past year, with almost no judicial process or legal paperwork. Detainees who most vigorously criticize the people and things they love are rewarded, and those who refuse to do so are punished with solitary confinement, beatings and food deprivation.

[…] Bekali was held in a cell, incommunicado, for a week, and then was driven 500 miles (804 kilometers) to Karamay’s Baijiantan District public security office.

There, they strapped him into a “tiger chair,” a device that clamped down his wrists and ankles. They also hung him by his wrists against a barred wall, just high enough so he would feel excruciating pressure in his shoulder unless he stood on the balls of his bare feet. They interrogated him about his work with a tourist agency inviting Chinese to apply for Kazakh tourist visas, which they claimed was a way to help Chinese Muslims escape.

“I haven’t committed any crimes!” Bekali yelled. [Source]

Shih also tweeted additional findings that did not make it into his story:

https://twitter.com/gerryshih/status/997094298821644290

At the Washington Post, Simon Denyer interviewed Bekali and Kayrat Samarkand, another former detainee who says he was targeted for being a Muslim who had visited Kazakhstan:

Samarkand said 5,700 people were detained in just one camp in the village of Karamagay, almost all ethnic Kazakhs and Uighurs, and not a single person from China’s Han majority ethnic group. About 200 were suspected of being “religious extremists,” he said, but others had been abroad for work or university, received phone calls from abroad, or simply had been seen worshiping at a mosque.

[…] The 30-year-old stayed in a dormitory with 14 other men. After the room was searched every morning, he said, the day began with two hours of study on subjects including “the spirit of the 19th Party Congress,” where Xi expounded his political dogma in a three-hour speech, and China’s policies on minorities and religion. Inmates would sing communist songs, chant “Long live Xi Jinping” and do military-style training in the afternoon before writing accounts of their day, he said.

[…] His account was corroborated by Omir Bekali, an ethnic Kazakh who was working in a tourism company in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital, until he was arrested by police on a visit to see his parents in the village of Shanshan in March 2017. Four days of interrogation, during which he was prevented from sleeping, were followed by seven months in a police cell and 20 days in a reeducation camp in the city of Karamay, he said. He was given no trial, he said, nor was he granted access to a lawyer. [Source]

The camps have been reported in recent months as part of an ongoing crackdown in the region, launched in 2014 and later extended, which is targeting the native Uyghur ethnic minority in an effort to stop violent attacks which have been carried out in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China. Rights groups and Uyghur exiles blame the crackdown on increased ethnic tensions and grievances among the Uyghur population, who have been subjected to religious fasting bans, local and region-wide rules against “extremist behavior” including wearing veils or beards, propaganda campaigns, a ban on “extreme” Islamic baby names, and more recently a biometric data collection system. The Chinese government has also turned Xinjiang into a testbed for new high-tech surveillance technologies, creating, in Adrian Zenz’s words, “perhaps the most heavily policed region on the planet.” Zenz also provides evidence of biometric data collection, despite government denials:

This week is Xinjiang fact checking week. Screenshot below: China foreign ministry denies @hrw allegations that Xinjiang collects vast amounts of DNA data. Now, compare this with the actual evidence… pic.twitter.com/UVP5dfiDO0

— Adrian Zenz (@adrianzenz) May 17, 2018

Yining City in Ili Prefecture: government notice about DNA and other biometric data collection from every resident aged 12-65. For "focus persons" in need of special attention and their families, the age limit is waived. https://t.co/QWcuy0RB8k pic.twitter.com/2tyeuH9MPn

— Adrian Zenz (@adrianzenz) May 17, 2018

Sorry, that was Yining County (not city), a Uyghur majority region.

— Adrian Zenz (@adrianzenz) May 17, 2018

Next is a township in Manas County (Altay prefecture), April this year, basically the same official notice about DNA and other biometrical data collection among residents aged 12-65. https://t.co/ezAhliDZFO pic.twitter.com/gL6gtORaVZ

— Adrian Zenz (@adrianzenz) May 17, 2018

Next: Yanqi Hui Autonomous County in Bayingholin Mongol Autonomous Prefecture – notice about biometrical (incl. DNA) data collection from Nov 2017, slightly different context here. https://t.co/kyj1l9JQ67 pic.twitter.com/mnvJE8i2yE

— Adrian Zenz (@adrianzenz) May 17, 2018

Some U.S. lawmakers have expressed concerns about the alleged use of American-made technologies in producing DNA sequencers used by Chinese police in Xinjiang.

The political indoctrination found in the reeducation camps is also taking place in different, and sometimes gentler, forms through “home visits” by Communist Party cadres to families in Xinjiang and “open” camps for people accused of minor crimes who are allowed to return home at night. According to a recent report from Human Rights Watch about the “home stays”:

“Muslim families across Xinjiang are now literally eating and sleeping under the watchful eye of the state in their own homes,” said Maya Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The latest drive adds to a whole host of pervasive – and perverse – controls on everyday life in Xinjiang.”

Since 2014, Xinjiang authorities have sent 200,000 cadres from government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and public institutions to regularly visit and surveil people. Authorities state that this initiative, known as “fanghuiju” (访惠聚, an acronym that stands for “Visit the People, Benefit the People, and Get Together the Hearts of the People” [访民情、惠民生、聚民心]), is broadly designed to “safeguard social stability.”

[…] The cadres perform several functions during their stay. They collect and update information about the families, such as whether they have local hukous – household registration – or are migrants from another region, their political views, and their religion. The visiting cadres observe and report on any “problems” or “unusual situations” – which can range from uncleanliness to alcoholism to the extent of religious beliefs – and act to “rectify” the situation. Cadres also carry out political indoctrination, including promoting “Xi Jinping Thought” and explaining the Chinese Communist Party’s “care” and “selflessness” in its policies toward Xinjiang. They also warn people against the dangers of “pan-Islamism,” “pan-Turkism,” and “pan-Kazakhism” – ideologies or identities that the government finds threatening. The authorities expect all of these to be done through “heart-to-heart” talks about everyday life. [Source]

Steven Jiang of CNN also reports on the home stays:

In numerous photos posted online, the authorities paint a picture of ethnic unity, showing smiling Han officials and minority families jointly preparing meals, doing household chores, playing sports and even sharing the same bed — images that Human Rights Watch’s Wang says put the “forced intimacy” element of the program on full display.

Government statements have stressed the program’s effectiveness in resolving people’s daily and social problems such as trash collection to alcoholism.

But in a speech last December, a top Xinjiang official made clear the scheme’s “strategic importance” in “maintaining social stability and achieving lasting security,” as well as instilling the political theory of President Xi Jinping in the minds of local residents.

A local government statement online also indicated that officials must inspect the homes they are staying for any religious elements or logos — and instructed the officials to confiscate any such items found in the house. [Source]

The crackdown in Xinjiang is being carried out alongside a broader government campaign to “Sinicize” religion and assimilate minorities, according to a report from the Uyghur Human Rights Project. Uyghur youth are being especially targeted, the South China Morning Post reports.

Uyghur children recite Chinese classics in Han Dynasty costumes to "reinforce their Chinese identity." Report: Chinese Government Accelerates Assimilative Policies for “Sinicization of Religion." Released today. @uyghurproject https://t.co/h7m4CeuBN3 pic.twitter.com/yXIpOwfEl5

— Louisa Coan Greve (@LouisaCGreve) May 9, 2018

In a sign that this campaign extends beyond the Muslim population of Xinjiang, Hui Chinese, who are ethnically close to Han Chinese but predominately Muslim, have also been required to get rid of Arabic signs and Islamic decor, despite their enjoying a greater degree of religious freedom than Uygurs in recent years, Nectar Gan reports for the South China Morning Post.

Historian Rian Thum writes for The New York Times about the impact of such policies, including mass incarceration, on the Muslim population of Xinjiang:

Over the last decade, the Xinjiang authorities have accelerated policies to reshape Uighurs’ habits — even, the state says, their thoughts. Local governments organize public ceremonies and signings asking ethnic minorities to pledge loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party; they hold mandatory re-education courses and forced dance performances, because some forms of Islam forbid dance. In some neighborhoods, security organs carry out regular assessments of the risk posed by residents: Uighurs get a 10 percent deduction on their score for ethnicity alone and lose another 10 percent if they pray daily.

[…] Many details of this carceral system are hidden, and remain unknown — in fact, even the camps’ ultimate purpose is not entirely clear.

[…] Tens of thousands of families have been torn apart; an entire culture is being criminalized. Some local officials use chilling language to describe the purpose of detention, such as “eradicating tumors” or spraying chemicals on crops to kill the “weeds.”

Labeling with a single word the deliberate and large-scale mistreatment of an ethnic group is tricky: Old terms often camouflage the specifics of new injustices. And drawing comparisons between the suffering of different groups is inherently fraught, potentially reductionist. But I would venture this statement to describe the plight of China’s Uighurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz today: Xinjiang has become a police state to rival North Korea, with a formalized racism on the order of South African apartheid. [Source]