When the management of a shopping mall in Nanjing decided to post some festive New Year’s decorations, little did they expect that the red and white floral and circular designs would make them the target of an ultranationalist vlogger. The vlogger had posted a video of himself pointing to the decorations and claiming that the red flowers resembled a Japanese “rising sun” motif and that the red circles suggested the Japanese national flag. He also scolded a mall manager, saying, “This is Nanjing, not Tokyo! Why are you putting up junk like this?” Afterward, local authorities intervened, the decorations were taken down, and the shopping mall management got off with a stern warning.

The offending decorations wished shoppers a “Happy 2024” and a “refreshing and blooming” New Year.

The incident calls to mind other recent examples of anti-Japanese sentiment, or “U-lock mentality,” in China. There was the Schadenfreude-tinged online rejoicing following a magnitude 7.6 earthquake that struck Japan’s Noto Peninsula on New Year’s Day, and the forced removal of a subway advertisement from Nanning’s Metro Line 2, after nationalist bloggers falsely claimed that the advert resembled Japan’s wartime “rising sun” flag.

Most recently, the Jimu News logo has found itself in the crosshairs, accused of being modeled on the Japanese flag:

Top: “Modeled after a certain flag?”

Some online trolls went a step further, taking issue with the two characters that make up Jimu’s name (极目, Jímù). If you were to remove the right-hand-side radical (及, jí) from the first character, they claimed, and add one stroke to the remaining radical (木, mù), it would yield the character 本 (běn). Then, if you were to remove one stroke from the second character, thus converting it from 目 (mù) to 日 (rì), the experiment would yield the two characters 日本 (Rìběn), meaning “Japan.”

For most sensible observers, this was a bridge too far. Even state-broadcaster CCTV seemed to have had enough of the farce, for it posted an article on its Weibo criticizing the blogger who had reported the Nanjing shopping mall decorations to the authorities. “Patriotism is not a business, and complaints should be based on evidence,” read the CCTV post. “This sort of unchecked tattling is detrimental to individuals, companies, and society as a whole.”

Some online sleuths also delved into the background of the nationalist blogger known as @战马行动 (zhànmǎ xíngdòng, “Operation Warhorse”), who appeared to be behind the Jimu controversy. WeChat current affairs blogger 押沙龙yashl (yāshālóng yashl) described some of Warhorse’s past xenophobic posts, republished screenshots showing comments from internet users who agreed with Warhorse, and noted that in recent days, WeChat searches for the nationalist blogger tended to yield only critical posts, with supportive content apparently buried, hidden, or deleted. The WeChat account for the Lingnan (Guangdong and Guangxi) Queer Center (岭南酷儿中心, Lǐngnán Kùér Zhōngxīn) mentioned Warhorse’s frequent homophobic pronouncements, such as his outrageous, unsubstantiated claims that “works of homosexual literature are funded by ‘foreign forces’” and that “unmanly men are the result of foreign propaganda promoting male effeminacy.”

Over the last week, CDT editors have archived a number of critical and satirical essays and articles that question the wisdom of allowing self-proclaimed online “patriots” to push a xenophobic agenda, hijack public sentiment, intimidate businesses, and interfere with normal economic activity—particularly during this economically fragile period.

The following is an excerpt from a photo essay by WeChat account 顾礼先生 (Gù Lǐ Xiānsheng, “Mr. Gu Li”), known for covering current affairs and social justice issues. Titled “I Knew Things Were Ridiculous, But I Didn’t Expect Them To Be This Ridiculous,” the essay details the Nanning Metro, Nanjing shopping mall, and Jimu News controversies, and wonders where it all will end:

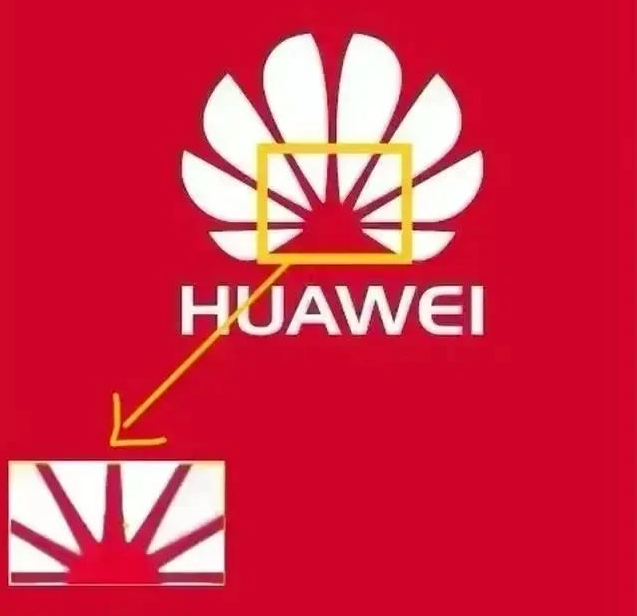

If this trend continues, Huawei might find itself in trouble next.

Zooming in on the Huawei logo

Traffic lights could be in danger.

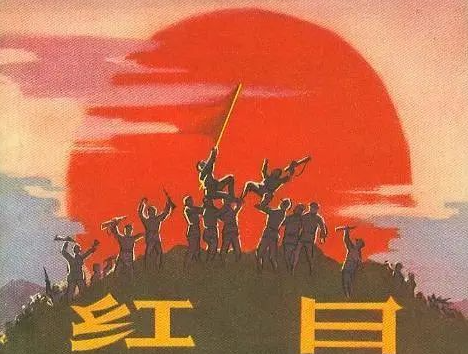

As could posters such as this.

A classic “patriotic” poster

And designs like this.

The logo of the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences

And anyone who sells red stickers online.

Ferris wheels, wheels, fans, and fireworks from all around the world could be in peril.

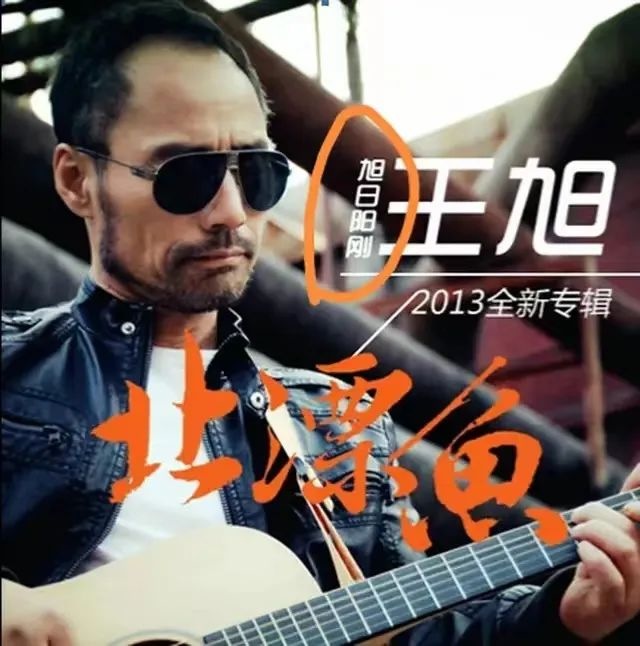

And this band (旭日阳刚, Xùrì yánggāng) had better change its name, unless it wants to be accused of harboring “ulterior motives.” [The first two characters of the band’s name, 旭日 Xùrì, mean “rising sun.”]

Cover of the 2013 album “Migrant Fish” (北漂鱼, Běipiāo yú), from musical duo Wang Xu and Liu Gang, who perform under the name “Xuri yanggang.”

Maybe it’s safer just to throw your cell phone away.

The “video record” button on the screen of a cell phone.

I guess even the sun is Japanese now.

[Chinese]

Another essay, by WeChat current affairs blogger “Princess Minmin,” expresses exasperation at the absurd lengths that ultranationalist bloggers will go to in order to generate traffic on their social media accounts, as well as concern that online hatred is seeping into the real economy, imperiling normal commercial activity:

Nowadays, a gang of so-called “patriotic bloggers” spend their days behaving like mental patients, complaining about red circles and despising any design that resembles the sun. Whereas they used to confine themselves to keyboard pounding and online screeds, now they’re showing up at brick-and-mortar stores to stir up trouble. Is allowing people like that to do whatever they please going to help attract more foreign investment, or hinder it? Do they help advance our economic development, or hold it back?

If the government wants to grow the economy, it has to increase its openness to the outside world. If the government wants its citizens to enjoy a good standard of living, will it continue to allow them to be bullied by these sort of people? [Chinese]

A photo essay by WeChat account 第五二六区 (Dì wǔ’èrliù qū, “District 526”) suggests a few other types of images that might end up verboten, and accuses anti-Japanese bloggers of being motivated by fame and fortune, rather than ideology:

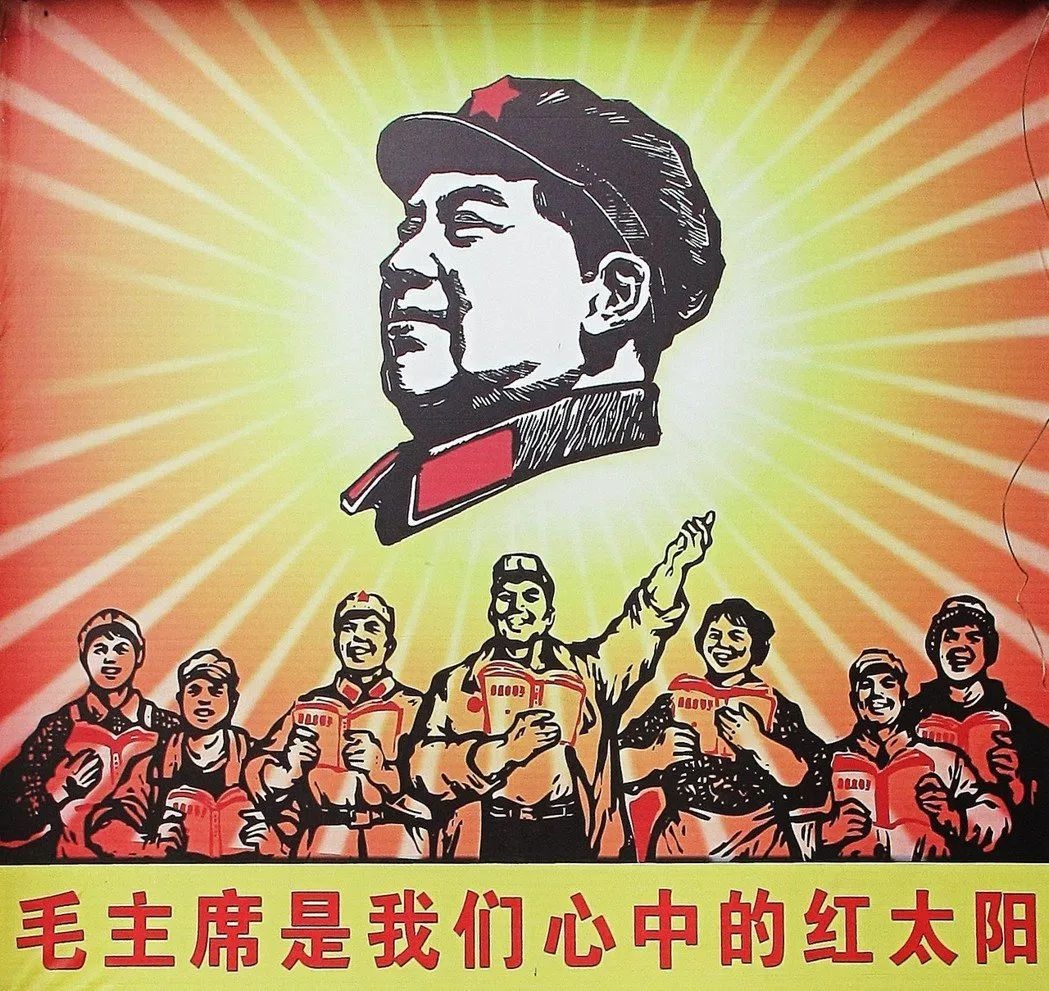

This classic image of Chairman Mao as the rising sun, emanating rays of sunlight, might be suspect, according to online anti-Japanese trolls. The caption reads: “Chairman Mao is the red sun in our hearts!”

Today they fly the banner of “patriotism” to reap online traffic and force merchants to kowtow, compromise, and remove advertisements. Who knows what evil they will commit tomorrow, in the name of “patriotism”? But they are not true patriots, just hooligans who pretend to be patriotic.

[…] So let me ask you: are there any true patriots among these whiny people whose minds are shackled by U-shaped locks? No, because all they care about is adding more online followers, becoming the next big online influencer, and raking in the cash! [Chinese]

Lastly, two recent articles examined the role of government and state-media criticism in chastising nationalist bloggers who go to extremes. Social and current affairs WeChat blog 冰川思享号 (Bīngchuān Sīxiǎnghào) mentioned a Communist Youth League critique of a crew of “patriotic” vloggers who, in September of 2021, flooded the zone with suspiciously similar-sounding videos about living in China’s border regions and feeling safe and well-protected by their government. Some of the vloggers said they were located near the Yalu River on the China-North Korea border, and others even claimed to be broadcasting from the non-existent “China-Japan border.” In response to this absurdity, a Communist Youth League article warned that “this sort of high-sounding ‘patriotic’ rhetoric, which plays on people’s emotions to drum up web traffic, is undoubtedly a blasphemy against genuine patriotic sentiment. To put it bluntly, it is ‘low-level red.’”

In the article “State Media Censure of ‘Scam-Style Patriotism’ Is a Spanking, Followed by a Candy,” WeChat account 老萧杂说 (Lǎo Xiāo záshuō) describes the mixed messages inherent in state-media scolding of nationalist bloggers:

Some people were shocked when they saw the news [about the state-media scolding]. I see the official media’s infrequent criticisms of patriotic populism as akin to a teacher rapping their knuckles on a chalkboard, reminding the class, “All right, it’s okay to have your bit of fun, but you needn’t behave boorishly.”

But don’t count on patriotic populism becoming docile. Its gradual trend towards extreme nationalism and xenophobia shows no sign of abating. [Chinese]