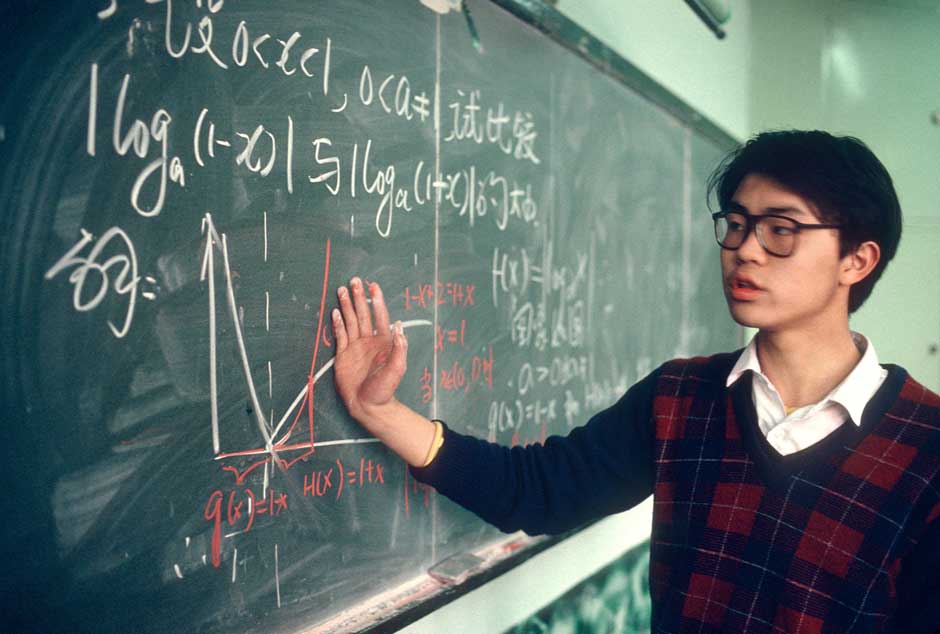

At The New York Times, Didi Kirsten Tatlow spoke with Yong Zhao, professor of education at the University of Oregon, about his new book, Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon: Why China Has the Best (and Worst) Education System in the World, and the “actively harmful” current state of China’s education system.

Q. Chinese educators have long tried to change the system, to “kill the witch of testing,” to ban homework, entrance examinations. Why do they continually fail?

A. There are many reasons, but primarily it is the authoritarian spirit that has put people in a “prisoner’s game.” Mei banfa [“there’s nothing to be done”] is a very common phrase I hear from my friends and colleagues in China when talking about why they allow their children to do certain things counter to their better judgment. I hear the same from policy makers and educators. They know what’s good for children, but they felt they are unable to change or if they take the first step to change, they will be punished because others won’t change.

Q. You write that “Chinese education is the complete opposite of what we need for the new era.” What do we need?

A. The education we need is actually quite simply “follow the child.” We need an education that enhances individual strengths, follows children’s passions and fosters their social-emotional development. We do not need an authoritarian education that aims to fix children’s deficits according to externally prescribed standards. I wrote about this in my last book, “World Class Learners: Educating Creative and Entrepreneurial Students” (Corwin Press, 2012). [Source]

In an interview with The New York Times’ Ian Johnson in April, Chinese educator Jiang Xueqin also spoke about the need and desire for education reform in China.

Jiang Xueqin: Since the late 1990s, there has been a shift in how parents viewed the Chinese educational system. In 1999, when I taught in China, you could argue that the gaokao system [the rigorous testing system that controls who gets into which universities] was at its apex. The gaokao was a good way to produce engineers and mid-level bureaucrats. It was perfect for these goals because it filters out people with the highest analytical intelligence. China in the 1980s and 1990s was basically a sweatshop economy. It was about organizing the masses and producing Nike sneakers for the American market. Everyone believed that the best route to success was to do well on the gaokao, get a degree in China, and then go to the United States for graduate school.

But starting around 2004 and 2005, the middle class was rising, more people were going overseas and seeing other cultures. They began to question the validity of a gaokao education. If China is to progress, it needs people with different skill sets. It needs entrepreneurs, designers, managers—the sort of people China doesn’t have. [Source]

Read more about China’s education gap and the vast disparity in education opportunities between students from rural areas and those from urban backgrounds.