Some recent restrictions placed on historical books, museum exhibits, and academic discourse have brought renewed attention to the Chinese Communist Party’s attempts to rewrite history, control the historical narrative, and combat what the Party perceives as “historical nihilism.”

Earlier this month, acclaimed historian and Xiamen University professor Yi Zhongtian’s 24-volume series on Chinese history was pulled from bookstore shelves after the publisher announced it was making revisions to the long-running series in order to “comply with official requirements.” “Yi Zhongtian’s History of China” (《易中天中华史》Yì Zhōngtiān Zhōnghuá Shǐ), which encompasses prehistoric China to the modern age, is the product of Yi’s decades of scholarship, as well as his popular history lectures on CCTV-10’s “Lecture Room” series. Overseas political analyst Liang Jing (梁京) once praised Yi Zhongtian for subverting the historical distortions of Chinese officialdom, and imbuing the telling of Chinese history “with the spirit and values of modern civilisation.”

An article from WeChat public account 进击的熊猫 (jìnjī de xióngmāo, “Attack Panda”) examines the political sensitivities behind the current “crisis” in the publication of history books, and suggests three possible reasons why the Party-state might have objected to Yi Zhongtian’s approach to Chinese history. The first is Yi’s argument that true Chinese civilization took hold approximately three and a half millennia ago, in contrast to the “5000 years of Chinese civilization” frequently quoted by state media and Party propagandists. The second is the fact that Yi’s assessments of historical figures and events often diverge from orthodox CCP interpretations, causing some to accuse him of “using the past to satirize the present.” The third reason is Yi’s lively, humorous, vernacular writing style, and his frequent use of contemporary slang and internet buzzwords to help modern readers relate to events in the distant, and not-so-distant, past. Some of Yi’s critics see this approach as disrespecting and belittling—or even distorting and tampering with—the serious business of Chinese history.

Some observers have suggested that Yi’s descriptions of certain historical figures are meant as critiques of China’s current leadership. His characterization of the late Eastern Han Dynasty general, politician, and warlord Yuan Shao (袁绍, d. 202 C.E.) as “tremendously ambitious but lacking in wisdom, ferocious yet cowardly, bitterly suspicious and unpopular” has been interpreted as a jab at Xi Jinping. This calls to mind the October 2023 recall of a book about the Chongzhen Emperor—the volume’s title, cover design, and cover blurbs were interpreted by some as being obliquely critical of Xi Jinping’s rule.

In recent years, examples of the Party’s tightening grip on the historical narrative have abounded: a university lecturer targeted for “distorting history,” a once-popular political figure elided from Party history, a TV drama canceled for promoting “historical nihilism,” a journalist imprisoned for insulting martyrs, a stand-up comedian banned and fined for supposedly mocking the military, and a rumored shutdown of Renmin University’s Qing History Project (led by historians critical of the “New Qing History”) for allegedly being “overly influenced by the New Qing History.” Meanwhile, the CCP has done its utmost to assure that nothing, not even historical fact, will impede the celebration of its own history.

The latest historical figure slated for erasure seems to be none other than Genghis Khan. As Bloomberg’s Terrence Edwards and Alan Wong report, amid a crackdown on Mongolian-language education in Inner Mongolia, references to the founder of the once-mighty Mongol Empire are being deleted from museums, plays, school curricula, and history books:

At the history museum in Hohhot, the Genghis Khan exhibit has been replaced by a display of artifacts presented as a history of China’s northern grasslands, capped with a quote echoing Xi that extols the need for a common Chinese identity.

“The sons and daughters of all ethnic groups in Inner Mongolia should remain closely united like the seeds of a pomegranate that stick together,” the sign read in Chinese, English and Mongolian. “And unswervingly nourish themselves with fine traditional Chinese culture.”

[…] Even fictional depictions of Mongolian culture are targets. In September, authorities in the Inner Mongolian city of Ordos ordered a 130-strong theater troupe from Mongolia to leave China after their performance of The Mongol Khan was terminated due to “force majeure” without having been staged even once. [Source]

The Chinese government’s attempts to rewrite the history of Genghis Khan have spread far beyond its borders. Writing for Nikkei Asia, Victor Mallet describes how the Chinese authorities’ insistence on “erasing” Genghis Khan and his empire from a French museum exhibition on that topic led the museum to partner instead with the Mongolian government:

Bertrand Guillet, director of the Nantes History Museum in the western French city, was shocked by […] an inexplicable demand from a partner museum in northern China. It said the artifacts it was sending to Nantes for an exhibition on Genghis Khan, the 13th-century Mongol emperor, could be displayed only if he or the empire he established was not mentioned.

[…] “They told us, ‘Don’t use the words Genghis Khan, don’t use the words Mongol empire. You’ve used the phrase Yuan dynasty (which ruled China for a century from the time of Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan) — don’t use it.’ Well, that’s difficult. You can’t have an exhibition about Genghis Khan without mentioning Genghis Khan.”

[…] The strange message about Genghis Khan was assumed to have originated not in Hohhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia, whose museum was supposed to supply the core of the exhibition, but in Beijing, where Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party were ramping up a global campaign to rewrite the history of China and Eurasia. “The new text was really a clear example of historical revisionism,” said Guillet, referring to the proposed exhibition synopsis sent to him from China. “It was unacceptable in terms of professional ethics, of historians’ ethics.”

[…] “For some years now there’s been a desire to rewrite history for the glory not only of the party but for a particular ethnic group, the majority Han,” said Antoine Bondaz, a researcher and China expert at France’s Foundation for Strategic Research think tank. “They are recreating Chinese history in a way that is unified, simplistic … to introduce more coherence and rub out the diversity of China.” [Source]

One might think that a “red drama” about the Chinese army, in a production backed by the military and Chengdu’s Party Propaganda Department, would be uncontroversial and hew closely to Party political orthodoxy. Last weekend, though, a video of “10 Questions from the Red Army” went viral, with many social media users noting that the questions could easily be applied to today’s political landscape. Among the questions posed by the soldier characters in the play: “Are the People in charge of the country?” “Are there still those who behave tyrannically and run roughshod over the People?” “Does the Party still remember its promises to the People?” and “When we need to stand up, will anyone be brave enough to take a stand?” Some online commenters noted that “every one of these questions is heartbreaking.” The video and some of the questions were posted on X by Li Ying (@whyyoutouzhele). The production’s current status is unclear.

The “Ten Questions” format has deep resonance, as it evokes similar lists of questions about COVID policy that circulated during the pandemic, particularly toward the end of last year. One such list was deleted by censors, and the WeChat account that posted it was permanently banned. Just last week, “Ten Questions About the Private Economy”—an article in which journalists from the financial publication Caijing interviewed four prominent Chinese economists about the state of the economy—was summarily deleted from WeChat.

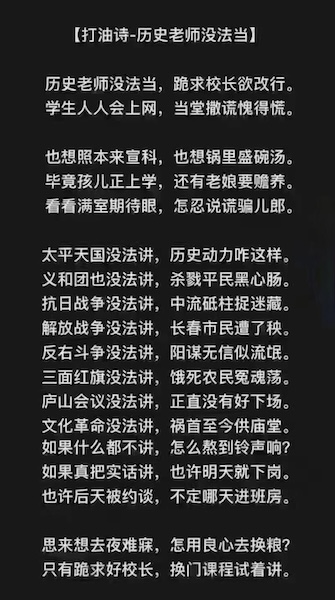

With history texts, academic discourse, performances, and exhibitions under such strict scrutiny, and so many topics off-limits, teaching history in mainland China has become a virtual minefield. “I Can’t Go On Teaching History,” a humorous poem that has been making the rounds on social media, provides a glimpse into the fraught existence of an ordinary history teacher:

“I Can’t Go On Teaching History”

I can’t go on teaching history—

Please, principal, just let me leave

The kids these days are all online,

And I’m ashamed to teach them liesI’ll stick to the script, ‘cause I’ve got to provide

My kid’s still in school, and then there’s my wife

My classroom’s full of hopeful eyes,

And I can’t bear to falsifyYou can’t teach the Taiping Rebellion anymore

Is this what history has in store?

Same goes for Boxer Rebellion

They slaughtered too many civilians

You can’t teach World War II and be right

Cause our Party stalwarts fled from the fight

You can’t teach the War of Liberation

Too many in Changchun died of starvation

You can’t teach the Anti-Rightist Campaign

The conspiracies seem too insane

Forget about the Great Leap Forward, People’s Communes

and Socialist Construction—

The victims of famine still haunt that destruction

You can’t teach the Lushan Conference, my friend

The good guys came to no good end

You can’t teach the Cultural Revolution, mate

The chief culprit’s still lying in stateIf you can’t teach these, or any old things,

How to pass the time until the school bell rings?

If I told the truth, I’d be laid off tomorrow

The day after that, I’d be called in for a chat

Then later, someday, I’d be locked in a cageI’m so worried, I can’t sleep at night

How to make a living, yet do what’s right?

Principal, I’m on my hands and knees—

Let me teach some other subject, please!

(source: internet/author unknown)