This week, China underwent its fourth Universal Periodic Review (UPR) at the U.N. This ritual is a rare occasion—occurring only once every four to five years—that forces the international community to jointly scrutinize China’s human rights record. (Every U.N. member state is subject to the process, which began its first cycle in 2008.) Years worth of abuses documented by individual victims and U.N. bodies alike provided ample opportunity for criticism, but a significant number of countries opted for tame statements. Many even praised China’s record. While it did not emerge unscathed, China did demonstrate that its long-running efforts to neuter U.N. criticism of its human rights abuses have, to a significant extent, paid off.

Looking ahead, the U.N. Human Rights Council (HRC) will adopt China’s UPR report in June, after China decides which recommendations to implement. China is then responsible for implementing them before its next UPR cycle in 2029. China will also be encouraged to publish a mid-term report, but it has never done so for past reviews. In 2018, China ostensibly accepted a notable proportion of recommendations, but rejected those relating to grave violations against Uyghurs and Tibetans and to its lack of cooperation with U.N. actors. The International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) has compiled a comprehensive repository of recommendations on human rights in China since 2018, issued by an array of U.N. human rights bodies, with separate repositories for Hong Kong and Macao.

ISHR’s Raphaël Viana David summarized China’s 2024 UPR session and highlighted some of the more critical oral recommendations:

As it faced a grilling of their human rights record at the United Nations, Chinese representatives doubled down on their denial of years’ worth of UN-vetted evidence pointing to a long list of human rights abuses, from a general crackdown on human rights defenders in mainland China and Hong Kong to possible crimes against humanity against Uyghurs and the cultural assimilation of Tibetans.

[…] Despite China’s efforts to lobby governments into repeating its own talking points and the constraining format of the meeting – which only allowed speakers a slot of 45 seconds -, at least 50 States made numerous, specific and detailed recommendations to Beijing on urgent issues.

These included, among others, explicit calls to place a moratorium on or outright abolish the death penalty; to grant unrestricted access to the country to UN human rights envoys and mandate holders, including in Xinjiang and Tibet; for China to ratify and effectively implement human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; to end widespread censorship and dismantle measures hindering freedom of association, assembly and expression for civil society, journalists and lawyers; to abolish the sweeping Hong Kong ‘National Security’ law ; and to end the widely documented practices of internment and family separations in Xinjiang and Tibet. [Source]

At ChinaFile just before this year’s session, Sophie Richardson and Rana Siu Inboden outlined the various ways that China manipulates the UPR process to its advantage:

First, the national report is a work of fiction straight from government officials and propaganda authorities. None of the grave human rights violations raised through other UN reviews or international civil society groups—from crimes against humanity to torture to rampant censorship—get a mention in Beijing’s report. It asserts it is “fostering historic achievements in the cause of human rights in China.” The only problems it admits: “obstacles . . . to promoting high-quality development” and “our ability to innovate in science and technology is not yet strong.”

A second tactic supports this deception: In clear violation of the UPR guidelines, Chinese authorities prohibit independent civil society in the country from participating in drafting the report. Since China’s 2018 UPR, Chinese officials have detained, disappeared, or driven into exile the environmentalists, feminists, lawyers, and other peaceful activists who could offer input. In 2013, Beijing authorities arbitrarily detained a human rights defender, Cao Shunli, who was trying to travel to Geneva to learn about UN human rights processes; she died in police custody in March 2014. The organizations listed as contributing to the 2024 UPR national report are all either organized by or uncritical of the government.

Third, Beijing works to ensure its allies offer up gushing praise in their remarks at the dialogue. It also encourages those governments to make recommendations that are so vague as to make it easy for Beijing to accept them and claim progress. At China’s 2018 UPR, Azerbaijan recommended that Beijing “consider including measures aimed at ensuring the increased efficiency and accountability of public services.” The Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, an independent human rights group, points out that some “recommendations” actually effectively endorse ongoing human rights abuses, such as Iran’s proposing that Beijing “safeguard its political system.”

Last but not least, the credibility of reviews can be affected by the relentless pressure Beijing applies to UN institutions. During its 2018 review, Chinese authorities succeeded in temporarily removing critical submissions from Hong Kong, Tibetan, and Uyghur groups. [Source]

All of these methods were on display during this UPR cycle. As Amnesty International’s China director Sarah Brooks stated, “The tragedy of this UPR review is that China’s time-tested tactic of repressing human rights defenders – whether in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong or elsewhere – means that those best placed to take this work forward were not in the room. They are silenced, in prison or otherwise detained, under surveillance, in exile.” Members of Students for a Free Tibet noted that certain unidentified Chinese individuals attempted to cut in line outside of the session and photograph Tibetans and Uyghurs. Stephanie Nebehay from the Geneva Observer reported on China’s efforts to bar individual activists from attending the session:

Beijing’s diplomatic mission has asked the United Nations in Geneva (UNOG) to ensure that “anti-China separatists” are not granted access to Tuesday’s session—attendance at which requires accreditation—and that no “anti-China” slogans or banners are tolerated on the premises. “Harassment activities inside Room XX are advised to be handled in a quiet, safe and swift manner so as to avoid disruptions to the review,” read China’s communication, seen by this reporter.

[…] Beijing’s latest salvo was accompanied by a request for “a special security plan” for its 60-strong official delegation, and a list of nearly two dozen Uyghur, Tibetan and Hong Kong activists whom it described as being “of concern.” It urged UN officials to reject any requests from the targeted activists and groups to organize side events. [Source]

Many never made it to that room! #CaoShunli bravely tried, but police her at the Beijing airport. She was horribly mistreated and eventually died in police custody in Mar 2014 as the @UN_HRC approved China's 2nd UPR report after China delegates disrupted a 1-min silence for her. https://t.co/Eqi3kG1jGJ

— Renee Xia (@ReneeXiaCHRD) January 24, 2024

Nonetheless, some Uyghur and Tibetan activists were able to organize protests outside of the session:

A protest to voice Tibetan and Uyghurs rights and denounce repression in #Tibet and #Xinjiang/ East Turkestan is taking place in front of the Palais des Nations! Coincided with the #ChinaUPR pic.twitter.com/eNXgUhmYAt

— ICT Brussels (@SaveTibet_EU) January 23, 2024

Yesterday, the World Uyghur Congress joined the #Uyghur and #Tibetan communities in front of the UN 🇺🇳 to protest against 🇨🇳's human rights abuses. pic.twitter.com/ldCxHGoVnt

— World Uyghur Congress (@UyghurCongress) January 24, 2024

The @UyghurProject joined allies this week for #ChinaUPR in Geneva 💪🏼💪🏼💪🏼

Following tireless advocacy, and the submission of detailed info on China's atrocities against Uyghurs— dozens of 🇺🇳 UN member states made strong, critical recommendations to China. pic.twitter.com/309diHl3cS

— Uyghur Human Rights Project (@UyghurProject) January 24, 2024

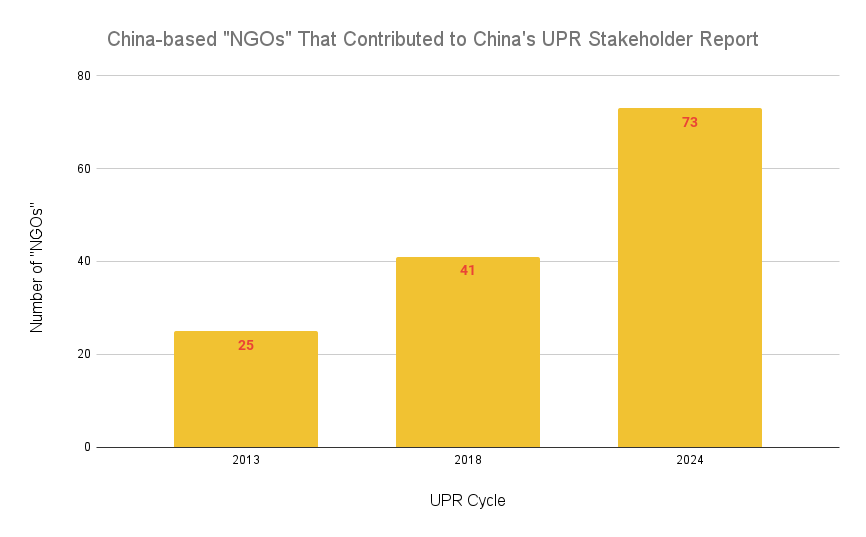

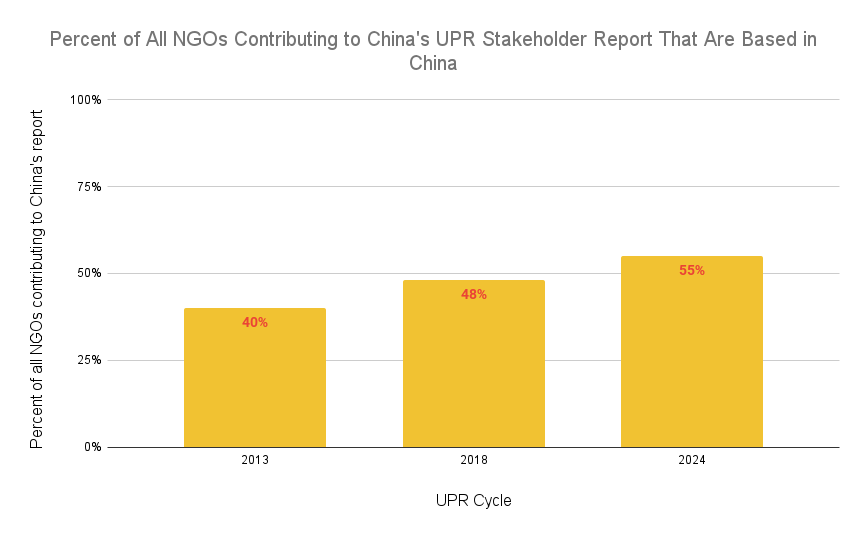

Another example of China’s attempts to subvert legitimate human rights criticism is found in the U.N.’s official “Summary of stakeholders’ submissions on China,” one of three main documents that guide the UPR. Human rights researchers have warned that China has tried to flood the zone by organizing groups to submit positive reports. Indeed, a CDT analysis shows that the number and percent of “civil society” organizations that the summary report lists as being from China has increased between each UPR cycle. This is notable given the legal obligations registered NGOs in China have towards supporting the CCP, which means that NGOs from China are more likely to make submissions supportive of China’s human rights record.

One China-based “NGO” that contributed to this year’s UPR stakeholder report was the China Society for Human Rights Studies, which hosts the China Human Rights Network. This network aims to “showcase the development achievements of China’s human rights cause [and] tell the story of China’s human rights.” It is also hosted by the Wuzhou Communication Center, which was established “to better spread China’s voice to the world” and has been awarded the title of “Key National Cultural Export Enterprise” for seven consecutive years by the CCP Central Committee’s propaganda department and other state bodies. This week, the network’s X (formerly Twitter) account was saturated with promotional videos about Xinjiang’s snow, trade, and kindergarten drama programs, and a “German manager impressed by China’s remarkable success.” It also shared a meme making fun of American democracy, as well as an open letter from other Chinese “civil society organizations” to the President of the U.N. HRC, claiming that other NGOs “fabricated lies, […] spread false information and cause[d] trouble on a large scale, with the purpose of attacking and smearing China.”

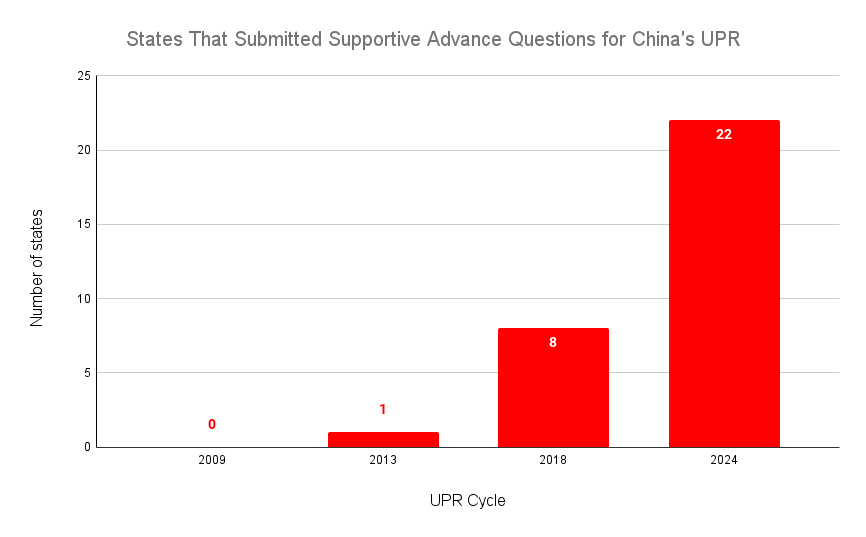

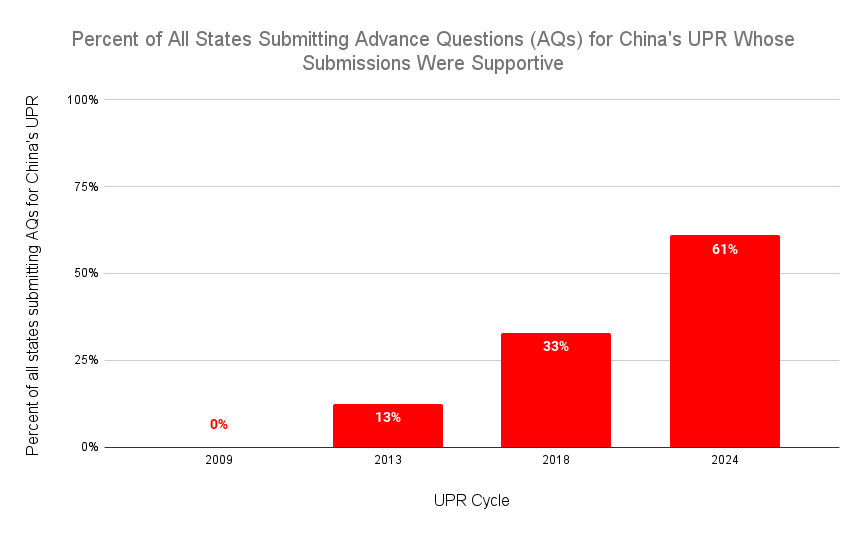

In the Jamestown China Brief, Anouk Wear explained how China has benefitted from another aspect of the UPR process, the submission of Advance Questions, which serve as a “useful litmus test for measuring the PRC’s relationships with U.N. Member States and how they have evolved over time”:

Initially, fewer countries submitted questions, and those questions genuinely criticized, raised concerns about, and asked for more details regarding specific topics. However, PRC-friendly states gradually began to submit questions that praised the PRC. Consider this Advanced Question, from Cuba in 2013: “China has made great achievements in the promotion and realization of the right to development. Would China share its experience in this regard?” The rapid increase of these questions reflects the PRC’s increasingly friendly relations with UN Member States and its ability to ask them to submit these supportive questions. This tactic strategically distorts the historical record and takes up time which could be spent addressing genuine human rights violations in the PRC. The PRC uses this to dilute and distract from criticism. Similarly, the oral Recommendations made by UN Member States at the UPR reveal that the PRC is able to garner increasing international support and influence States to endorse their strategies at the UN, rather than constructively criticize the PRC despite this being the main purpose of the UPR. [Source]

Building off of Wear’s data, a CDT analysis of the Advance Questions submitted during China’s 2024 UPR cycle shows that this trend has intensified. This time, 22 out of 36 states (61 percent) issued Advance Questions that were positive or supportive of China. This is a significant increase from the last UPR cycle in 2018, when only 8 out of 24 states (33 percent) did so, and from the prior UPR cycle in 2013, when only 1 out of 8 states (12.5 percent) did so. The 22 states issuing supportive Advance Questions this year are Algeria, Antigua and Barbuda, Bangladesh, Belarus, Bolia, Burundi, Cameroon, Cuba, North Korea, Eritrea, Iran, Laos, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, Slovenia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Venezuela, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe.

Another way to measure shifting U.N. member-state support for China during its UPR is through the oral statements made during the session itself, as categorized by Nathan Ruser, an analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute:

Overall, 6 countries were highly supportive of China (essentially writing statements that would be identical to if Chinese officials had written them themselves), 77 were generally supportive, 32 were neutral and 42 were critical. pic.twitter.com/k1NlOIxnWQ

— Nathan Ruser (@Nrg8000) January 25, 2024

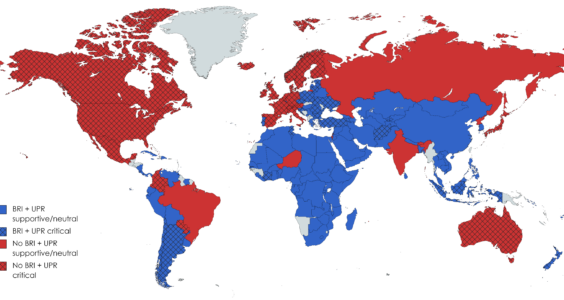

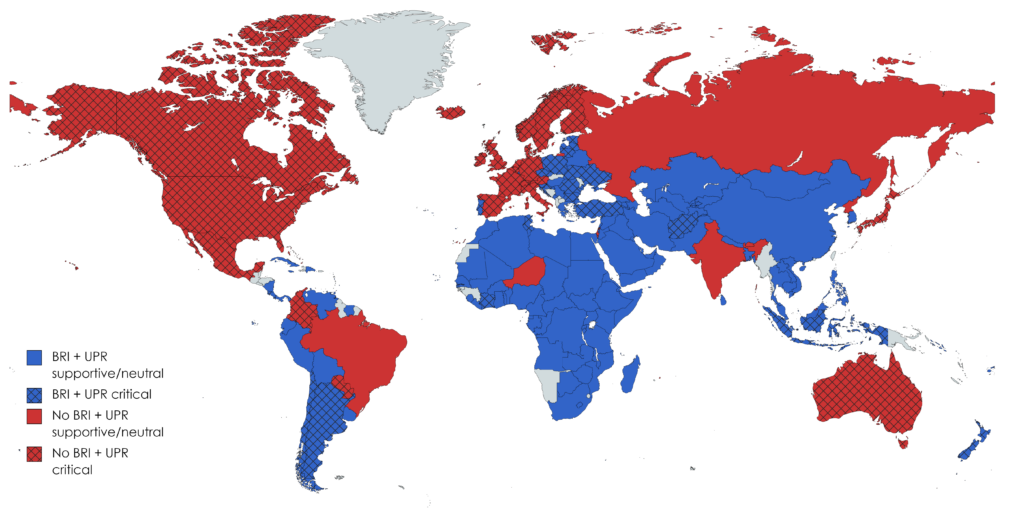

CDT conducted another brief analysis comparing the level of support of states’ oral statements at China’s UPR with those states’ affiliation to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). We used Ruser’s data to label states’ level of support, with those scoring above 1.0 considered supportive, those below -1.0 considered critical, and those between -1.0 and 1.0 considered neutral. We then used Fudan University’s Green Finance & Development Center’s list of countries that signed a BRI-related Memorandum of Understanding with China, while updating the BRI status of certain countries to reflect recent changes.* The results show a striking correlation between participation in the BRI and support for China in the UPR.

Among the 161 states that made statements at China’s UPR session, 128 have participated in the BRI and 33 have not. Regarding the statements, 91 were supportive, 19 were neutral, and 51 were critical. When cross-referenced, the data reveals that 102 states that have participated in the BRI gave supportive or neutral responses, which equals 80 percent of all of these BRI states, or 63 percent of all BRI and non-BRI states at China’s UPR. Meanwhile, 8 of the 33 (24 percent) non-BRI states gave supportive or neutral statements. These correlations are illustrated in the map below.

What we are witnessing today in China's UPR is a stain in history. I hope democracies worldwide take note of the enormous power China wields over countries in the global south. Disappointment is an understatement as to what's unfolding before our eyes as civil society reps; https://t.co/fgrZDICLq5

— Rayhan E. Asat (@RayhanAsat) January 23, 2024

The conduct of some U.N. actors further supported China’s attempts to evade criticism. Absent from the U.N.’s compilation of its own internal assessments on China’s human rights record for the UPR was the most damning assertion from the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ own August 2022 report on Xinjiang, which concluded that Beijing’s policies “may constitute […] crimes against humanity.” Moreover, the High Commissioner, Volker Turk, was absent from this session, to the ire of human rights activists: “Refusing to condemn Beijing, he ran away to Liechtenstein,” summarized Kenneth Roth, former Human Rights Watch director.

https://twitter.com/tingdc/status/1749828564256538662

A quinquennial event where CCP's authoritarian friends said nice things about Beijing's human rights while Western democracies slammed its abuses, against the backdrop of the chief UN human rights officer hid in Liechtenstein enjoying nice scenery: https://t.co/UPdY9Ss4g7 https://t.co/lXz1pGLDg7

— Yaqiu Wang 王亚秋 (@Yaqiu) January 23, 2024

*Due to the scarcity of official information, it is sometimes difficult to determine certain states’ official relationship with the BRI. We therefore welcome any feedback on our final list, which may not be perfectly up to date.