The Chinese government will pursue reforms to its Re-education Through Labor (RTL) system, according to a report in Xinhua News which followed a national political and legal work conference in Beijing on Monday. From the state-run Global Times:

Secretary of the Commission for Political and Legal Affairs of the CPC Central Committee Meng Jianzhu told the conference that the CPC Central Committee has deliberated over (the reform) and “the system of re-education through labor is expected to come to a stop this year once the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) approves the proposal,” the Xinhua News Agency reported Monday.

According to caixin.com, Meng also said that before approval by the NPC Standing Committee, the use of re-education penalties should be strictly controlled, and the system shouldn’t be applied to petitioners.

However, Meng’s statement on the “stopping” of the system disappeared on major news portals within hours.

Responding to a question about the brief appearance of the news, Qu Xinjiu, a criminal law professor with the China University of Political Science and Law, told the Global Times that “The government has been very careful when dealing with the re-education through labor problem.”

“There are loopholes in China’s current legal system where people who threaten the safety of others are not necessarily subject to punishment by the law,” Qu said. “China may not be fully ready to abolish the re-education policy until we have figured out a way to close the loopholes.”

China’s RTL system, or “Laodong Jiaoyang” (劳动教养), was established in the 1950s and allows public security officials to detain criminals and dissidents in labor camps without the benefit of a judicial hearing. The Ministry of Justice’s Bureau of Re-education Through Labor Administration estimated that there were 160,000 people in 350 camps as of the end of 2008, though a United Nations Human Rights Council working group put the tally at 190,000 in an early 2009 report. Prominent voices within China have come out against the RTL system, most recently when police sent the mother of a rape victim in Hunan Province to a labor camp in August 2012 for “disruption of social order.”

The Global Times added that Monday’s news “sparked widespread celebration among the public,” with one former village official calling it “a major step forward in judicial reform.” Chen Dongsheng, a bureau chief of the Justice Ministry’s Legal Daily, attended the conference and relayed Meng’s statement to The Associated Press:

The proposal must first be sent to China’s legislature, the National People’s Congress, for approval, Chen quoted Meng as saying.

Chen said he heard Meng make the pledge at a conference carried on closed-circuit television. China’s supreme court and other government offices declined to comment, although the respected independent magazine Caixin said it had confirmed Chen’s report with an unidentified conference participant.

“Meng said the reeducation system had played a useful role in the past but conditions had now changed,” Chen told The Associated Press in a telephone interview.

NPR’s Louisa Lim spoke with former village official and outspoken RTL critic Ren Jianyu, who spent time in a labor camp as a young adult and “had a mixed reaction” to the news:

“When I first saw the news, I was very happy. At least it’s a small step toward reform. It shows a trend in the top leadership,” he says. “But the road is still very long.”

A propaganda film about one labor camp shows blue-suited inmates bent over their work making electrical wiring. The inmates make computer cables and headphones for MP3 players.

Ren says he worked for about 10 hours a day, during which he was not allowed to speak to fellow inmates. He seldom had a day off.

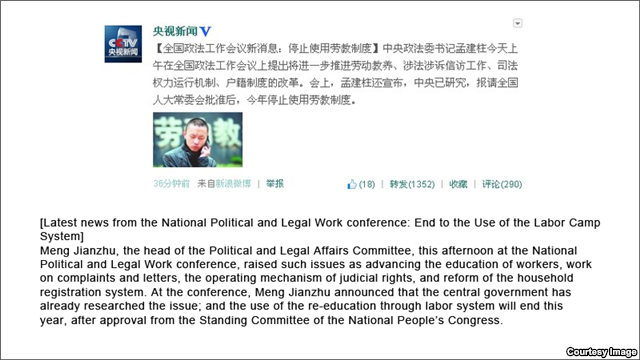

It was unclear, however, what shape any reforms would take as the official announcement contained few details. In addition, some microblog posts touting the news did not stay up for long. Voice of America posted a screen shot of a CCTV post that was later removed:

Andrew Jacobs of The New York Times noted that the way in which the news emerged, with statements by Cheng and others appearing briefly before being deleted, may have quelled any optimism that the system may go away completely. And human rights researcher Joshua Rosenzweig expressed skepticism while tweeting in real-time as news of the reforms began to vanish from Chinese social media:

Official media outlets’ posts on RTL starting to disappear from Weibo h/t @chinanalyst

— Joshua Rosenzweig (@siweiluozi) January 7, 2013

Xinhua: China to reform re-education through labor systembit.ly/117uCBV // this tells me nothing

— Joshua Rosenzweig (@siweiluozi) January 7, 2013

“劳教” doesn’t appear anywhere in Legal Daily front-page coverage of CCPL work conference

— Joshua Rosenzweig (@siweiluozi) January 7, 2013

Similarly, in a Monday press release, Amnesty International’s Roseann Rife cautioned that more detail was needed on the reforms:

“If these reports are true, clearly this is a step in the right direction, but the proposed reforms are unclear and need to be spelled out in detail and subject to open public debate.

“The danger is the authorities’ rhetoric creates a veneer of reform without the reality changing for the hundreds of thousands of people detained in such facilities nor is it clear that any new system will meet international standards.”

China has “been debating how to change its labor camp system for much of the past decade,” according to The Telegraph’s Malcom Moore, who reported that four major Chinese cities debuted an alternative pilot system last year. But Nicholas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch tweeted that while the announcement itself is a step in the right direction, anything short of completely ending the program will be disappointing:

Meng Jianzhu’s annoucement that China is to “stop” using Reeducation-through-labor is big news. But what will replace it?

— Nicholas Bequelin 林伟 (@Bequelin) January 7, 2013

Xi Jinping is sending a strong signal with the RTL announcement. The Gong’an has lost some of the political clout it had under Hu.

— Nicholas Bequelin 林伟 (@Bequelin) January 7, 2013

What the int. community should say now is “No ‘RTL-light’ system to replace Reeducation-Through-Labor please! Only abolition will do.”

— Nicholas Bequelin 林伟 (@Bequelin) January 7, 2013

In a Tuesday press release, Human Rights Watched echoed Bequelin’s sentiment that China should abolish the RTL system entirely:

“This decision, if it truly put an end to Re-Education Through Labor, would be an indisputable step towards establishing rule of law in China,” said Sophie Richardson, China director. “Courageous activists and ordinary citizens have long fought to end this system of arbitrary detention.”

…

Human Rights Watch urged the Chinese government to abolish the RTL system entirely and determine new laws that establish a system to punish minor crimes, one that is consistent with the Chinese Constitution as well as its international human rights obligations. The judiciary – not the police –should be responsible for considering charges, determining guilt, and assigning appropriate punishment. Individuals accused must have access to court proceedings, the right to assistance of counsel of choice, and all other fair trial guarantees. The Chinese government should also explore alternative measures other than detention for minor offenses, such as compulsory community service. In addition, the Chinese government should take measures to eradicate torture and other cruel and inhuman treatment in its detention facilities and prosecute those responsible.

“Cosmetic changes to the system or cutting down the amount of time served in administrative detention will do nothing to end RTL’s notorious abuses, and might only further entrench the system,” said Richardson. “Only abolition will suffice, and it is time that the new administration of Xi Jinping takes steps towards ensuring due process.”